Posts by Bill Ryan

SE Alaska’s awesome, melting glaciers

Cruise passengers get close to Marjorie Glacier. (Bill Ryan)

SOUTHEAST ALASKA’S CALVING GLACIERS are an apt symbol of nature’s response to a warming environment. Glacier Bay also holds a historic lesson about the cataclysmic consequences rapid climate change can have for human communities.

It is a rare privilege to visit the icy waters of Glacier Bay National Park. Only a few boats at a time are permitted to view the towering ice walls where glaciers come down from majestic mountains to the bay. Access is limited, especially to protect the bay’s multitudinous humpback whales.

Marjorie Glacier is constantly calving (Bill Ryan)

Brother Andy had secured a precious permit, allowing us to come from Juneau and enter the park. We took Osprey up to the park’s two grandest glaciers, staying far enough away to avoid being swamped when large ice chunks splashed into the frigid water, and gently weaving our way through the ice bits floating all around. Our little boat shared one inlet with a colossal cruise ship, and the other with a busy whale and seals floating on ice.

Tlingit totem at Bartlett Cove (Bill Ryan)

Bill Ryan catches a glacier ice chunk for the cooler

Heading south, we were suddenly surrounded by a half dozen feeding humpbacks. We spent a lazy afternoon anchored in a otherwise quiet cove as a couple of noisy whales blowed and splashed about.

Johns Hopkins Inlet (Bill Ryan)

As night fell, an urgent radio call interrupted our reverie. A small fishing boat with an elderly crew member had run out of fuel just a few miles away. No one else was nearby. We pulled anchor and sped toward a distant spotlight to deliver the one can of gas we had onboard to the relieved fishermen.

Across Icy Strait from the park, we docked at Hoonah, a mostly Tlingit town now a stop for thousands of cruise ship passengers. Here we learned from locals about the catastrophe that befell their ancestors who dwelled around Glacier Bay until 1754. Two exceptionally cold years—possibly due to distant volcanic eruptions that darkened the sky—produced a huge, fast-moving glacier that filled the entire bay. The few people who survived were forced to flee south to a place they called Xunaa, meaning safe from the north wind. Descendants speak reverently about the homeland few ever get to visit.

Circling gulls follow humpback’s progress (Bill Ryan)

Humpback blows before Gilman Glacier (Bill Ryan)

Between stops in wilderness anchorages we visited a couple of very friendly towns. Tiny Tenakee Springs offered a mineral bath and a cafe proprietor offering cinnamon rolls and helpful local boating knowledge. In Kake, the ex-minor league ballplayer who brought us fuel drove us around, pointing out black bears feasting on salmon in a creek running through town.

Tenakee Hot Springs

We lucked out with an unexpected string of sunny, warm days as we motored south through wild big islands. At Kuiu Island we kayaked with herons and loons. After cautiously transversing the aptly named Rocky Pass in Kuiu Strait, we spotted an orca heading down Sumner Strait.

Gulls monitor traffic in John’s Hopkins Inlet (Bill Ryan)

Petersburg Harbor

From Petersburg we ventured up to LeConte Glacier, the Western Hemisphere’s southern most tidewater glacier. Up close, the face cracked and boomed as pieces fell off. The giant creature-like shapes of blue ice floating outside the inlet were captivating.

Andy dropped me off in Wrangell and took on his next crew member eager to experience Alaska’s awesomeness from the water.

Humpback quartet in Glacier Bay. (Bill Ryan)

Teamwork (Bill Ryan)

Bald eagle over Tarr Inlet (Bill Ryan)

Sea otters float on their backs to eat (Bill Ryan)

Orca swims alongside us in Sumner Strait (Bill Ryan)

Kayakers in Tarr Inlet. (Bill Ryan)

Ice creatures guard LeConte glacier (Bill Ryan)

LeConte glacier (Bill Ryan)

In the Great Bear Rainforest

Along the north coast (Bill Ryan)

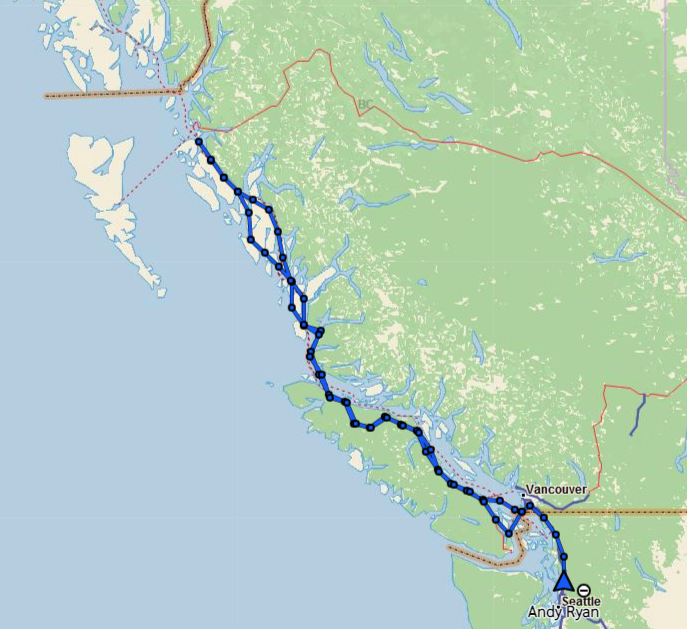

Cruising British Columbia’s divine coastal waters in a compact motorboat last month, two boomer siblings had a splendid wilderness adventure.

Andy Ryan, from Kenmore, Wash., planned the excursion and captained the Osprey, a sturdy, 22-foot C-Dory. Brother Bill Ryan, a New Yorker, took photos and helped navigate.

Canada opened to Covid-vaccinated foreigners in August, creating a small window for travel to the Great Bear Rainforest before harsh weather set in. A lifelong boater, Andy had taken Osprey in 2019 up the Inside Passage from Washington to Alaska’s Glacier Bay and back, and was keen to revisit the renowned nature preserve. Novice Bill had crewed on an Alaska leg of the earlier voyage and eagerly agreed to come along.

BY BILL RYAN

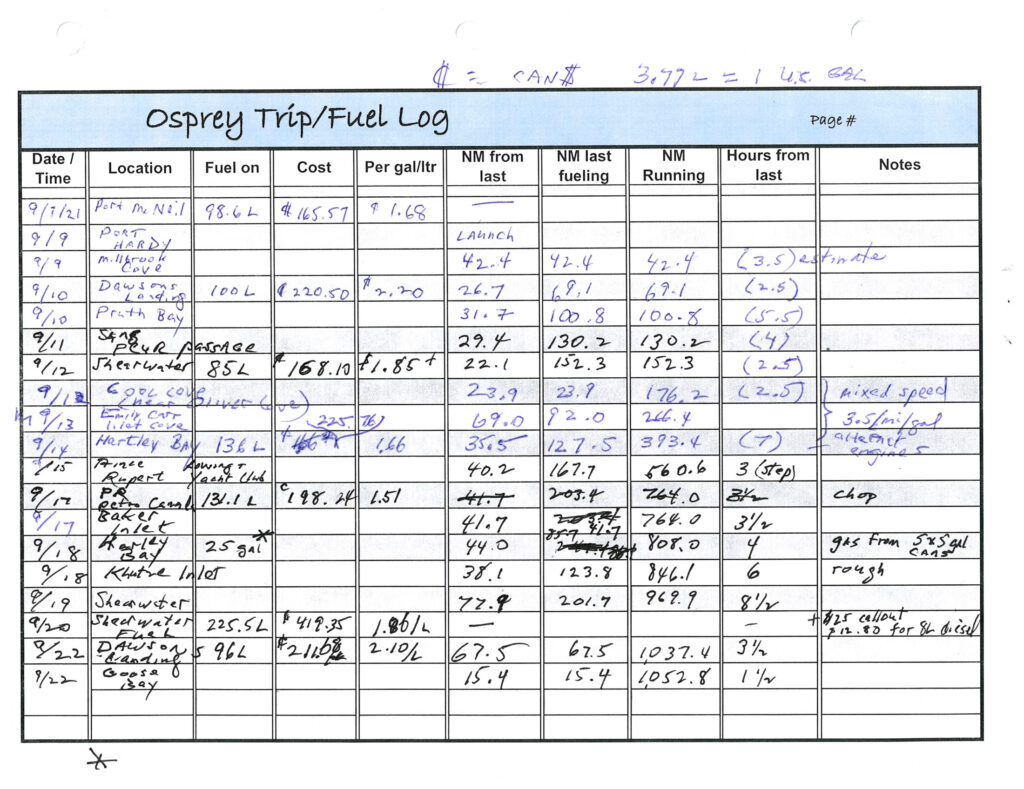

On Sept. 7, we trailered Osprey across the border, onto a ferry to Vancouver Island and up to Port Hardy before launching into Queen Charlotte Strait. Our first challenge was rounding unprotected Cape Caution, where wind- and current-driven waves mix with Pacific swell in a tricky chop. Stay alert, peer through thick boat-length-visibility fog and watch for floating logs!

Over the next three weeks, we made our way north through picturesque passages between forested islands to Prince Rupert, near Alaska, and back again. At night we anchored in sheltered inlets recommended by prior mariners using the Active Captain app. Mountains with stunning waterfalls ringed some of the anchorages.

Andy (left) and Bill Ryan

Trusty Explorer pulled loaded Osprey and kayaks from Everett, Wash. to Port Hardy, BC, and back. (Bill Ryan)

Waiting for the tide before launching at Port Hardy. (Bill Ryan)

(Bill Ryan)

(Bill Ryan)

(Bill Ryan)

Along the way we spotted more than a dozen humpback whales, their blows visible from far across the water. Some traveled in processions. A few appeared close by; one broached near our starboard side.

A procession of whales (Bill Ryan)

Near Klemtu, tragically, we noticed a mass of seaweed in motion. Approaching, we saw a humpback whale, apparently trying to free itself from a tangle of fishing net and kelp. We circled helplessly as it floundered; there was nothing we could do and we motored north in search of help.

A few miles further up the east coast of Swindle Island, we spotted a Kitasoo/Xai’xais Guardian Watchmen boat. Pulling alongside, we reported the trapped marine mammal and its location. The young Watchmen seemed to believe there was a good chance of saving the whale, and sped off to the rescue. Andy has attempted to find out what became of the hapless cetacean, but thus far has not been able to connect with the Guardian Watchmen. He will keep trying. Bill shot video of the whale, and it is awful to watch. But we don’t see any good reason to sanitize our account. The video is posted here.

Whale tangled in rope and kelp (from video).

Coastal Guardian Watchmen, First Nations environmental protectors (Bill Ryan)

We only ventured ashore a few times in the Great Bear Rainforest, and always at places with docks. The shores were rocky and slippery, and there weren’t many good places to land. The pristine area, now mostly protected from logging, is home to white “spirit bears,” a subspecies of the American black bear, revered by local native people. We did not see any, but did sight one of their black bear cousins on a beach as we motored by.

During a normal summer, these waterways would be thick with pleasure boats and cruise ships. But this year, post-season, we rarely saw another boat—an occasional tug pulling an enormous barge or a big BC Ferries ship. We had days of wooded solitude between far-apart fuel stops.

Bill at the helm (Andy Ryan)

Sighting a black bear (Ursus Americanus) on the north shoreline of Hunter Island (Bill Ryan)

B.C. ferry in the distance (Bill Ryan)

Getting a little too close for comfort (Bill Ryan)

Sadly, due to Covid, Klemtu, Bella Bella and other First Nations communities on our route were closed to visitors. But we spent several days at the welcoming Shearwater Resort, newly aquired and managed by the Heitsuk Nation, while we waited for a strong gale to pass.

With Klemtu closed and our gas running low, it looked as though our trip might be cut short; fortunately, the fuel dock at the village of Hartley Bay—a two-day trip, 66 nautical miles north of Klemtu—was open for business. With our gas tanks now full, we headed up gorgeous Grenville Channel—waterfalls on each side for 45 miles—and on to Prince Rupert, the farthest north city on the B.C, coast.

We were now just 24 miles from the Alaska border … but Prince Rupert was the end of the line for us. Summer was but a memory on the north coast. The wet, windy season had set in, with one low pressure system rolling in after another, and we decided not to risk a crossing of notoriously rough Dixon Entrance, with Ketchikan just a few more hours to the north. Instead, we hunkered down in driving rain for a couple of days, rocking gently in a slip at the Prince Rupert Rowing and Yacht Club. (Hot showers and a laundromat! Sweet!) Then we headed back south.

We had planned on gassing up again at Hartley Bay, but—oops!—the fuel dock was closed that day. We reduced our speed to save gas (Osprey doesn’t have tremendous range) and crept south. After two nervous days we made it back to Shearwater … on fumes … just in time for another powerful storm that kept us pinned to the dock for two days.

On our way south from Shearwater, we made a stop at the Hakai Institute on Calvert Island, where scientists study the ocean’s DNA and carbon levels. From there, we stretched our legs and walked to a gorgeous beach.

Bill at Hakai beach (Andy Ryan)

View from Hakai Beach (Andy Ryan)

Rock formation at Hakai Institute beach (Andy Ryan)

English garden at Hakai Institute (Andy Ryan)

OK, let’s wrap this tale up in one paragraph.

Another big weather system was closing in, and we took advantage of a momentary calm and dashed back across Queen Charlotte Sound at 20 knots to Port Hardy, pulled Osprey out of the water and began the long drive home.

And then there was that surreal late night incident at a decrepit motel in Nanaimo, where a scary tweaker threatened us, convincingly, with a homemade sword he’d had hidden under his coat. But that’s another story.

Vancouver Island and the Great Bear Rainforest (Navionics)

Track of the Osprey, September 2021 (captured by Garmin inReach device)

Log of the Osprey

Petersburg to Juneau: creatures abound

Seals floating in Endicott Arm near Dawes Glacier (Bill Ryan)

ALASKA’S FAUNA WERE ON FULL DISPLAY as the Osprey made her way to Juneau from Wrangell. Brown bears, seals, eagles and ice animals practically posed as we went by, a photographer’s dream.

We stocked up in Petersburg, a scenic, orderly fishing town proud of its founders’ Norwegian and Native heritage. Sally Dwyer, a longtime civic leader, gave us a fascinating VIP tour.

Houses along Petersburg’s Hammer Slough (Bill Ryan)

For the next five days we cruised into the wilderness to see animals, snow-capped mountains and glaciers, on a blessed run of sunny days. At night we anchored in protected coves, after reading reviews by other mariners and gingerly sounding the surrounding depths.

Entering Stephens Passage from Frederick Sound we crossed a virtual whale highway. We heard spouting and saw dozens of plumes in all directions, and from afar glimpsed a few tails reflecting sunlight as they flopped into the water.

Near shore, eagles were constantly overhead.

Bald eagle watching over Windham Bay (Bill Ryan)

At Hokham Bay we first encountered jagged icebergs calved from glaciers at the ends of Tracy Arm and Endicott Arm. Gleaming in the morning sun, some odd shapes suggested birds, lizards or dragons.

Ice menagerie: What manner of creature is this? (Bill Ryan)

Rising at 4 a.m. to meet the tide, we made our way up to the challenging entrance of Ford’s Terror inlet—named for a frightened sailor who navigated the roiling rapids in a rowboat—and at slack water went through carefully, into a secluded paradise enclosed by stunning high cliffs and waterfalls. No gargantuan cruise ships here.

View from our anchorage at Ford’s Terror (Bill Ryan)

We stayed long enough for two short kayak rides to a beach at one end of this idyllic basin. Rounding a bend, I suddenly came upon a mama brown bear and two small cubs digging for crabs or clams. After backing off to avoid notice, I took pictures from the kayak, rueing my lack of a longer lens. The mother and cubs then swam across a rising creek and vanished in the woods.

Brown bears dig the beach at Ford’s Terror (Bill Ryan)

When the tide was higher, I paddled back to their digging site, now an island, and found bear tracks and multiple holes in the sand.

Remnants of the three bears’ beach excursion (Bill Ryan)

The next day we continued up Endicott Arm to Dawes Glacier, weaving through a maze of small icebergs. Seals basked idly on many of these floats.

‘You looking at me?’ (Bill Ryan)

We got as close as we prudently could to the massive ice cliffs where the glacier meets the water, sharing the awing experience with kayakers from a swanky yacht.

Dawes Glacier (Photo: Bill Ryan)

We anchored for the night near the entrance of Tracy Arm, another fjord famous for icebergs, sharing the cove with tour boats and pleasure craft. As we pulled in, we spotted a brown bear family walking along slowly along the shore, as I and other tourists in inflatable rafts snapped pictures. Then they saw us and slipped behind the tall grass.

Foraging bears seem at first not to notice the spectators offshore (Bill Ryan)

Now they see us (Bill Ryan)

A trio of eagles watched from a rock as we pulled out into windy Stephens Passage, where we faced two- to three-foot waves from several directions. Our ride toward Juneau was bumpy but manageable, and the mountains on all sides were magnificent.

Eagles rest between fishing flights (Bill Ryan)

On our last night out in this leg of Osprey’s journey we anchored by a beach in a tranquil cove off Admiralty Island, reputed home to North America’s largest brown bear population. No creatures were sighted onshore, but in a sunset that lasted past midnight we listened to a nearby whale’s spouting and splashing, sounds that boomed across the water. Suddenly there was a commotion, and close behind our stern up popped two seals swirling in a close embrace.

Seal pas de deux in the sunset (Bill Ryan)

After a couple of days’ respite and a crew change in Juneau, brother Andy and his cozy C-Dory will head off to the natural glories of Glacier Bay. Bon voyage. Quelle aventure.