Up in Smoke

(Kathy Curtis-Johnson)

KATHY C-J AND I WERE SPEEDING EAST on the Yellowhead Highway along the wide Skeena River, about 42 miles from Prince Rupert, heading for Seattle 1,000 miles away. We had pulled Osprey out of the salt water the day before, after spending a final night aboard, tied up at the Prince Rupert Rowing and Yacht Club. Kathy was reading The Milepost, looking for a good place to pull the boaterhome over for the night. Terrace, B.C. looked like a likely spot. Maybe Smithers.

British Columbia’s Yellowhead Highway, along the Skeena River (Source: GerthMichael/Wikipedia)

In the side mirror, I thought I saw a little smoke coming out of the tailpipe, and started looking for a place to pull over. But the busy highway was long and winding, with cars and trucks zipping by in either direction and only soft, skinny shoulders on each side. By the time I spotted a narrow strip with safe room to park, dense black smoke was pouring out of the engine. It looked like it was on fire. A message on the instrument panel said something was wrong with the transmission.

(Kathy Curtis-Johnson)

There was a trail of black, shiny transmission fluid on the pavement for some distance behind the Explorer; and although I have never personally experienced a blown tranny, there wasn’t much doubt that our forward progress was at an end for a while. A long while, as it turned out.

Fortunately, we had just enough cellphone bars to reach Marla, in Seattle—who was able to send Marty from Wayne’s Towing out the highway to rescue us. But there’s a labor shortage up here, and it will be close to a month before any Prince Rupert auto shop will be able to repair the Explorer; and—after a week of involuntary tourism in Prince Rupert—Kathy and I will be flying back to Seattle in the morning.

But I need to say this: I can’t think of a better place to be delayed by a blown tranny than beautiful Prince Rupert, with its kind, friendly, helpful folks. This is my fourth time here; I love this place.

Marty Johnson, who grabbed a friend, dropped everything and brought two trucks to rescue us (one for the Explorer, one for the boat) is a great example of the decent, generous people who inhabit this region. He even offered to let Kathy and me use his house while we arranged repairs for the Explorer. Thanks Marty.

With luck—and my luck has been mostly good on this fantastic two-month voyage—I’ll be back up here in mid-September, to pick up my repaired SUV, hook up the trailer and bring Osprey home.

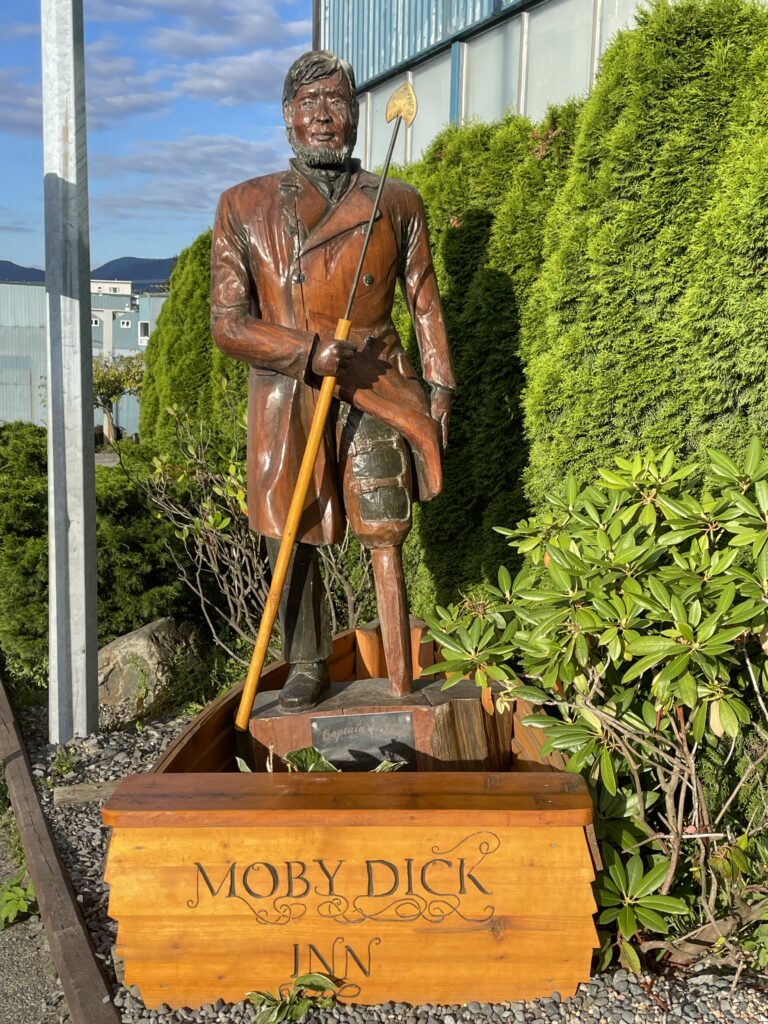

Capt. Ahab outside Prince Rupert’s Moby Dick Inn (Kathy Curtis-Johnson)

Two tugs and Osprey at commercial dock, Port Edward (Kathy Curtis-Johnson)

Gillnet on Port Edward commercial dock (Kathy Curtis-Johnson)

Mussels and barnacles on dock piling, Port Edward (Kathy Curtis-Johnson)

The 1953 storm

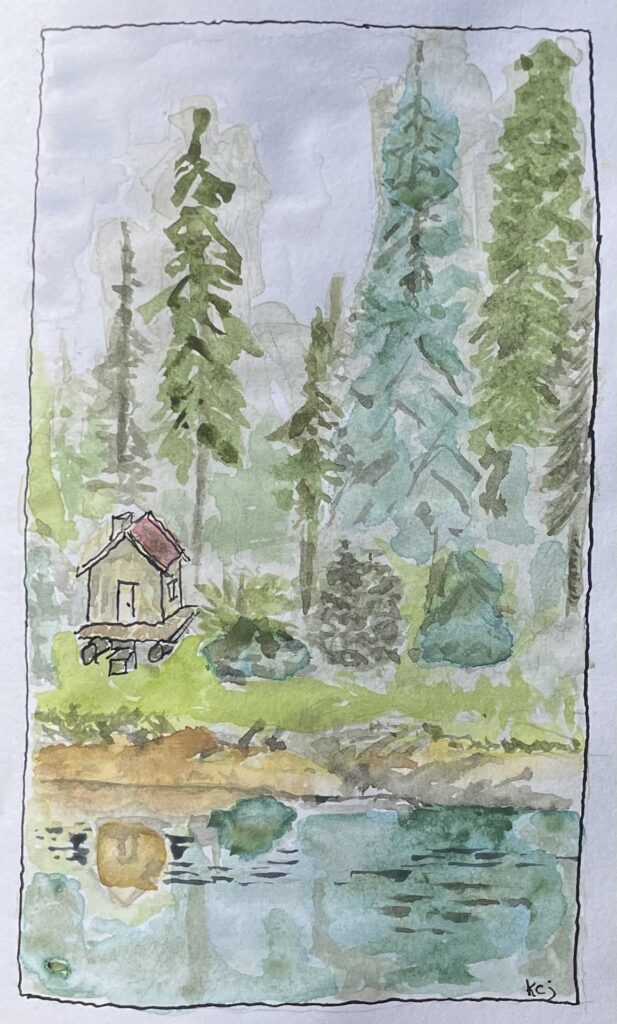

Watercolor of Pigot Bay R & R cabin circa 1953, as imagined by Kathy Curtis-Johnson

KATHY CURTIS-JOHNSON JOINED OSPREY five days ago, in Wrangell. Since then we have had a series of adventures, which included an invigorating passage down stormy Clarence Strait, in high winds and steep seas. Safe and warm now, tied to the transient dock in Ketchikan’s Bar Harbor, Kathy shares a story from her father—who had a considerably more perilous Alaskan adventure in 1953, when he served as a wildlife enforcement officer in Prince William Sound.

By Don Johnson, Copyright 2007

Part I

My 14-foot skiff had just sunk and wallowed below the surface, 25 feet from shore. I sat in the pouring rain on that narrow stretch of beach, cold, wet, hungry, lonely, angry and generally miserable, trying in vain to get a fire started, as darkness fell.

I was here in Alaska, enjoying the wilderness, as advertised on the bulletin board in the Wildlife School of Washington State College. The opportunity of a lifetime, to visit the Territory of Alaska, at the expense of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They would pay our fare north to Cordova, where we would be assigned a boat to rove the waters of Prince William Sound. We would be assisting the permanent staff, as enforcement patrolmen, to minimize violations of commercial fishing regulations. We would even receive substantial wages for the summer. It sounded too good to be true to me, as I was raised on the shore of Puget Sound and loved to fish.

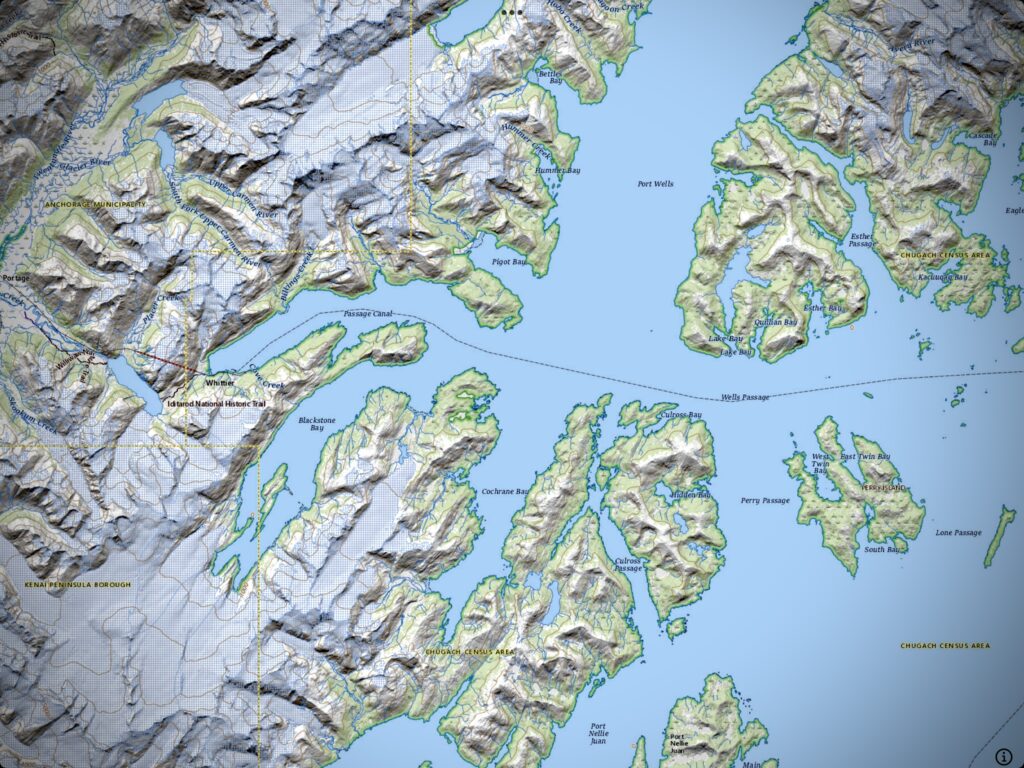

Scene of Don Johnson’s 1953 adventure: Port Wells, Pigot Bay, and Cochrane Bay, in Alaska’s Prince William Sound (Topo Maps+)

So this was what enforcement patrol was all about. Living in a tent on the beach and keeping track of the commercial fishermen on the water. With my boat sunk, no fire, and no way to walk out, I sure would welcome one of those big fishermen now.

This wasn’t how a “quick day trip” was supposed to end. The day had dawned bright and clear and relatively calm and no plans had been made for any extended stay or emergency. Nor had I left any note to indicate which direction I had planned to patrol, or how long I planned to be gone from my camp on the beach. I’d just had a quick breakfast, laundered clothes in a pool in the creek where I drew my camp water, and motored up the mile to the mouth of Pigot River to fish for trout. While there I inspected the status of the sled house cabin, brought in for rest and recuperation by servicemen stationed at Whittier, an outpost military installation during the territory days of Alaska. It was well stocked with supplies and in good order. Having recently returned from a short military assignment in Korea, I looked at the cabin as an alternate base in case of some emergency at my camp, a mile down the beach.

On the spur of the moment I decided to to go back to Cochrane Arm, the site of an arrest I had made the previous week. I was anxious to get out on the water again after having been cooped up in the soggy tent for several days after returning from the trial. I expected to be back to my camp well before dark.

I didn’t return to the tent to gather those items I would normally take on any venture that may terminate with inclement weather.

Each of us field men was set up in small tents on the beach, miles apart, near rivers where there were vulnerable runs of salmon at the mouths of streams. We were supplied with a barrel or two of premixed gasoline for our outboard motors, and white gas for our Coleman stove and lantern, and supplies which we purchased at the local grocery in Cordova prior to our departure. Each man operated on his own without any means of communication with any other field man.

The task of the field man was primarily as a “visual deterrent” to overeager commercial fishermen. “Stay out on the water among the fishermen” was the order of the day. No radios were issued to Fish and Wildlife patrolmen in those days; but commercial fisherman had radios aboard their vessels, which gave them a great advantage in many respects.

In my haste to get back onto the water the usual planning for weather changes which might require extra gear, food, fuel or shelter hadn’t even been considered. I didn’t even take the time to stop by my campsite for my anchor, axe, flashlight, and other equipment. Tired of being cooped up, I just left Pigot Bay and headed for Cochrane Arm and my rock pile about eight miles to the south.

I found my rock pile just as I had left it. Within an hour of my departure from the cabin I had concealed my skiff from view of passing ships behind the small, familiar rock pile, as I had done the afternoon of the arrest. Now was the time for waiting and patience. I commenced to review the circumstances of the previous arrest and hoped for a repeat. Time passes rapidly while reminiscing about a recent success.

Several days before, at dusk, I had apprehended three intoxicated Native cannery fishermen, far inside of legal salmon fishing grounds. At the time I didn’t realize just how fortunate I was that they were Native fishermen whose Nellie Juan Cannery quickly paid their meager fines of $100 each.

Their 20-foot boat had slipped by just at dusk heading into illegal waters. Painted green above and grey below and traveling without lights, one would have missed them if their noiseless movement had been against against a shoreline background.

My heart was racing as I gave them about 15 minutes before I followed and found them with their seine full of humpback salmon, at the mouth of a small stream. I was armed with a single-shot, 20-gauge shotgun and my .22 pistol but felt very vulnerable as I pulled up to their craft. It was dark by then and I had no idea who they were or what my reception might be.

They gave me no trouble at all and were far more congenial than I had expected when I requested permission to board their vessel and arrested them. They released their seine-full of fish as directed and I further directed them to go to Cordova for trial before the Commissioner. I held a few fish for evidence, took photos of the three with my 828 pocket camera from the hatch cover and later made contact with a cannery scow at Culross Bay. The photos looked like the lens cover was still on but it may have impressed them with the sophistication of the Service. I radioed my supervisor of the arrests and the need for the plane to pick me up for the trial a day or so later.

In hindsight, Captain Joe Tobenkoff and his crew did me quite a favor. I found later that had they been “creek-robbing non-Natives,” they could have lost their boat and gear worth many thousands of dollars besides, plus receiving a substantial fine. I might not have been so anxious to chase violators after dark as the case had been. I would not have been the first patrolman to disappear in Alaskan waters with no evidence of foul play.

The weather held fair for an hour or so at my rock pile hideout and then the wind came directly out of Port Wells into Cochrane Arm. Port Wells was a long reach of big water where no land obstruction broke the momentum and force of the waves. It was time to leave for camp in Pigot Bay, eight miles to the north.

Heading home meant crossing Cochrane Arm to the west shore. By the time I reached mid channel, 4 to 5 foot waves were capping and I was bailing whenever necessary.

It was then, that one blade of the three bladed propeller, just crystallized off. Hadn’t hit anything, it just snapped off. The motor commenced to cavitate so badly I thought it might self-destruct. I had no choice but to continue to try to reach the west shore. I carried oars but the heavy weather conditions were more conducive to praying than rowing. So I did! Loud and clear!

My gas supply was running low too but I had no alternative. I must reach the west shore if I was to escape the growing storm. While it was no more than two miles across, it seemed to take forever to see any progress, quartering across the wind as we were. Finally, within a hundred yards of shore I looked for some sheltered spot to land the skiff. There was none! She would pound herself to pieces on the rocks if taken to shore and she was too heavy for me to move her out of the water.

Fortunately, I spotted a very long, naked, whippy spruce tree lying on the surface and angled away from the wind at less than a right angle to shore. Its root structure lay well up on the bank. With more than a little luck, and some of those leftover prayers, I managed to draw my long, nylon rope, attached to the skiff’s bow ring, under the fish-rod tip of the spruce, and let the wind sweep the skiff back to shore I knew that the engine was vital if I were ever to reach camp again.

Tired and wet as I was, I managed to remove the 10-horsepower Johnson, the gas can, the oars, my rifle, the bailing can and whatever gear remained in the skiff, to the narrow sliver of beach above the tide. Then, I pulled the drain plug and drew the skiff out to within about eight feet of that lonely, naked spruce that obviously had weathered many a storm. Ever pray for a tree? I did! The spruce held firm and within a few minutes my skiff had filled with water and wallowed peacefully above whatever rocks lay below, under the pounding waves.

Part II

Now was the time I needed to get warm, dry and rested. A blazing fire is the most pleasant companion one could ask when alone in the wilderness. However, despite my efforts to get a fire started with some of my precious supply of gasoline, I was unable to do so. There was no fuel along that narrow slip of beach and my axe was still at the tent.

This had been a wet summer, I was limited in movement along the precipitous shoreline, dusk was approaching and I was exhausted.

Huddled in my raincoat, hip boots and sou’wester, with the Johnson motor and gas can as a windbreak and the ancient kapok life preserver for protection of my head above and below, I watched the remaining daylight slip into the semi-darkness of an Alaskan night and listened to my stomach remind me that I had missed both lunch and dinner. I tried to think of alternatives to my predicament but the time for productive planning was long past. My anger at my reckless departure was self directed. I had camped and hunted and fished throughout the mountains of Washington often enough to know that I should never have left camp so unprepared. I slept fitfully throughout the stormy night, praying that my fish pole spruce would hold firm as the tide receded.

Since walking out was not really a reasonable alternative my life depended on survival of my skiff. With hip boots as footgear, climbing the sharp peaks and traversing ice fields and glaciers was out of the question. I knew the terrain and the distances to be traveled just well enough to know that I must rely on the skiff and protect it at all costs.

Morning dawned with the wind still coming down from Port Wells. I was exhausted from the previous day’s stressful activity and very hungry. The tide had receded and my wooden skiff lay bow down on a boulder beach. It was some distance from the water’s edge, half full of water, but thankfully it appeared still undamaged. The fishpole spruce had also survived, ready for more action if the need arose.

I walked the beach for awhile to loosen up and get the kinks out after a rather bad night on a rocky bed. Working my way back to the skiff I knew that I must be prepared to leave if the wind eased up a bit. Some of the water in the skiff had drained out through the drain plug port, but now several alternatives faced me. Should I bail out the skiff immediately or wait till the wind abated. The wind might just continue and I would have to rely on that spruce for another night.

The thought of spending another night on this narrow sliver of beach was depressing. I must be ready to motor north along the west shore if the wind reduced a bit. I might find a cove further north where I could find some shelter and protection for the skiff and myself. Moving that heavy skiff to the water’s edge was going to take time and require considerable energy. The last and least desirable alternative was to stay where I was and rely on that spruce until the weather broke or some ghost ship arrived to rescue me.

What window of time might be required to travel the estimated seven to eight miles back to Pigot Bay with an engine that must be run at minimum speed because of the loss of one blade of the propeller. I had no idea if it would last the journey as I would be traveling almost due north into the wind coming down Port Wells. I don’t know if I was more worried about the engine or the pitiful amount of gas left in the tank.

Sitting there on the shore, considering the alternatives, I felt a slight decrease in the wind and made my decision. Right or wrong, I would bail the skiff now, put the drain plug back in, and prepare to try to get the 400-pound skiff back to the waters edge. I really disliked leaving the security of that great spruce, which had served me so well in the emergency landing, but the thought of spending another night on this sliver of beach spurred me on. If the wind dropped at all I would have to make the attempt to reduce the distance to the mouth of Cochrane Bay.

Perhaps I could find a cove further north with some protection from the wind. I would be moving toward the juncture of Cochrane Bay with Blackstone Bay and Passage Canal, up which I knew lay the military outpost of Whittier. There would be far more chance that I might be spotted on the shore there than here in this desolate spot.

Bailing warmed me considerably. The next step was to find some slippery, water-soaked limbs to get under the skiff and use as skids to the water and protect the bottom from hanging up on barnacles. A metal keel strip does not slide easily over rock, sand or barnacles. I found a waterlogged limb big enough for a lever and boulders aplenty to use as fulcrums. After a couple of hours or so I managed to get the skiff to the incoming water’s edge.

Reloading the motor, gas can, rifle and the rest of the gear was tiring, but warming. In anticipation of moving to a more favorable location, I put my bulky life jacket back on, launched my sturdy craft and said goodbye to the whippy spruce. Starting the little 10-horse Johnson I slowly made my way along the west shoreline of Cochrane Arm. The wind moderated for a while and we made good progress. The hillside had become less precipitous and I sensed a change in the landscape.

As the wind proceeded to rise again I was happily surprised to find us at the mouth of a cove that extended for some distance inland It probably was Surprise Cove, an old log booming site in earlier years. As we received some relief from the wind I took up my oars to spare my gas supply and proceeded to row inland a short distance. I thought about rowing to the head of the cove to explore but remembering how tired I was and how long it had taken me to move the skiff down to the water’s edge earlier in the day, I reconsidered and discarded that idea.

The cove was not deep and was soft bottomed at this site when probed with an oar. Lacking the anchor, still at camp, I thrust the oar as deep into the muddy bottom as I could, thinking that it would keep us in place till the wind and the rain eased a bit. I secured the skiff to the oar, confident that we would remain in place here, within a reasonable distance of the shoreline should the tide go out.

It was a relief to escape the direct wind. I could see the waves capping beyond the mouth of the cove. The rain continued pelting down harder than ever. It was the incessant rain that finally drove me under cover. My efforts of the day had dried my woolen clothes somewhat and I knew I could sleep anywhere if I could just lie down.

The only shelter from the pelting rain was under the three-foot bow cover of my skiff. I bailed all the water I could from the skiff and lying with my head and upper body under the bow cover, on the kapok pillow, immediately went to sleep. I seemed to have lost all track of time and my thoughts were related only to the wind, the distance from camp and the constant rain on the bow cover.

I slept the sleep of the dead. But even the dead would have been wakened by that cold water slipping under his wool shirt and down his neck. I remember having to get up to bail the skiff several times, then returning to my shelter, only to be awakened each time by that cold rain water down my neck My weight and the rising rainwater in the skiff, funneled to the narrow bow, had combined to send a rivulet of cold water down my neck. Surely, it was the Devil’s own alarm clock, with an automatic, cold, wet, snooze alarm. Only when the skiff bottomed did it cease to annoy me and I slept peacefully on.

Part III

Slowly I wakened in the predawn light of day, if day it was. An Alaskan night could easily be taken for a dismal day. I was quite comfortable there under the bow cover as my body heat must have warmed my wool shirt, even if it didn’t dry it. I tried to bring the events of the previous days into focus. We had made it to shore despite the storm and the broken propeller. A great spruce had somehow protected the skiff. Our landing was on a narrow sliver of shore that didn’t afford any shelter. All my equipment had been moved to shore and the engine had been saved. Our gas supply was desperately low and I was very hungry.

Sleep had overtaken me and was about to again. Just thinking about moving that heavy skiff, on skids, to the waters edge made me ache all over. That was why I had done the best I could, without an anchor, to keep the skiff within a reasonable distance of deeper water, if the tide were to go out. It was time for me to crawl out and see what fortune the day had brought. Being an optimist, I anticipated getting right back on the water as soon as possible.

The rain had let up and the wind had died appreciably, so, following the previous days pattern, the tide should be going out. Wrong, the tide had gone out, and the skiff lay on a muddy flat over a hundred yards from the waters edge. Time now was of the essence. Again, the press of the moment pushed my hunger back from immediate concern. I should be on the water right now, as the wind had diminished with the outgoing tide. However, I knew from sad experience, that it was going to be a strenuous task to get the skiff to the distant shoreline.

I remembered shoving the oar into the mud to tether the skiff and looked for it. It wasn’t visible around the boat and a moment of panic seized me. If the oar was lost, we were in even more serious trouble. When we ran out of gas then we would be dependent on those oars for getting back to camp or anywhere. I checked the bowline and soon found the missing oar, out of sight, but close against the side of the skiff. A relief to say the least. Oars were old friends and I was a good oarsman but you needed two.

I knew well the procedure for moving the heavy skiff to the shore and it was going to be a long day. I had to scour the mudflat for some distance to find the necessary slimy branches for skids and haul them to the skiff. It seemed to take forever just to locate the skids and get them in place. It would be even more difficult now than it had been on the downward sloping, rocky shore, with an empty skiff the day before. Now it was loaded with an engine and whatever gear I had still onboard.

So I commenced, moving the skiff two to three feet at a time, toward the distant shoreline, then replacing the skids under the keel strip, before the bow went off the forward-most skid. Pushing against the stern or the motor required lifting as well and was very tiring. Where was my haul-back when I needed it most? Haul back? I hadn’t thought of such a contrivance since I left camp. Now the memory came back to me. I hadn’t returned to get my anchor and other important gear because of the time it would take to disassemble the haul back I had rigged at camp. We patrolmen had discussed the quickest way to get our skiffs into the water in the event that a violation was reported in our patrol area or visible to us from shore. The beach slope at my campsite had been conducive to the installation of a device, simple in nature, to double line though the handle of a gallon jug. The jug itself was attached to the anchor, firmly imbedded in the sand, by a length of line. One could pull his floating skiff out over the anchor and tie it off, leaving the skiff in deeper water. That accounted for leaving the anchor but it was of no help now.

Slowly, very slowly, we crabbed our way toward the shoreline. It wasn’t long before the rain and the wind commenced again and I suspected that the tide was on the rise. It couldn’t come in fast enough for me. This field man was exhausted! Finally, I could see incoming water on the flat but continued to push the skiff, feeling that every minute that passed would cause me to question my judgment as to an immediate departure toward camp. We had about three miles of open water to cross, directly toward Port Wells, with no land on any side for protection or alternate destination in some emergency, like running out of gas.

The moment of truth was about to arrive as the water finally began to rise about the little skiff with its injured engine. Would I, or should I, chicken out as the storm continued to rise with the incoming tide? My stomach made the final decision. We go!

Part IV

Putting my kapok life jacket back on again and checking the gas can for the last time, I was ready to leave as soon as we were afloat. The gas tank had less than a gallon left. Up here, among waters directly off the glaciers, one would likely survive for twenty minutes or less if forced into the sea. I wasn’t planning on it. As I headed around Cochrane Point, the full force of the waves made me appreciate just what a stable and seaworthy little 14-foot skiff I was fortunate enough to have. They also gave me a bit of a fright as green water several inches deep came over the bow cover.

How that motor continued to operate with only two blades I have often wondered, but it did, despite it’s grumbling, and we very slowly moved away from Cochrane Point. I found it was necessary to bail as green water came over the bow cover when I ran too closely into the wind. I had to give way a few degrees to one side or the other to minimize the bailing. It was hard to estimate the height of the capping waves but they were above any I had ever been in before in a small boat.

Was I frightened? Frankly, yes! And I seriously questioned why I had not

waited for a more favorable launching time. Today must have been Sunday, for

I found myself praying more than usual. Slowly we made progress and before long we had covered a third of the distance between Point Cochrane and Pigot Point. I say “we,” as it was man and boat against the sea! We evidently still had some gas, as the crippled little engine continued to move us along. I

began to consider our course of action when we did run out of gas. Preliminary thought had already determined that we put the wind from Port Wells as near our stern as possible. Then the oars would come into play and we would move westerly toward Decision Point and the entry to Passage Canal, up which lay the post of Whittier, roughly ten miles away.

Had I been too optimistic, by heading north instead of west, when we first launched with such a limited gas supply? The decision had been made and it would avail us nothing to change course now.

Holding into the wind as much as possible each wave seemed bigger than the

last. Each one another challenge. Trying to go too closely into the wind just forced me to bail more often and not give my full attention to the next wave. Every wave now, capping as they were, was capable of swamping the skiff if I fell inattentive. I began to quarter a bit more to lessen the need for bailing. Surely we must have reached the midway point by now.

Looking astern, I saw that we were actually more than halfway to Pigot Point. I could almost smell those eggs and bacon at camp. If only our gas held out!

The engine sputtered a time or two and I thought that was the end of it. I first suspected that it was dirt in the gas. I was ready to man the oars but looking at the near-empty gas can saw that the waves had pitched it a bit to the side and it was not feeding the engine properly. That was quickly corrected and the engine got back to its offbeat operation. Now we were just off Pigot Point with the engine still moving us along. If the engine and gas held up, WE WERE GOING TO MAKE IT HOME!

It seemed like only a few minutes later that we entered the mouth of Pigot Bay and felt some relief from the constant wind from Port Wells. If the engine gave up now or ran out of gas, I could row to camp, a mile away. We didn’t need to, for the crippled, little engine continued on.

Going into the bay and breathing a prayer of relief, I noticed small white objects along the shore near my camp. It was my laundry, that had earlier been set out to dry. But the laundry could wait. It was time to get to shore. We were home.

I tipped up the outboard and left it on the skiff. Then, securing the boat to the haulback, I checked the gas can and found no more than a quart remained in the tank. I unloaded all my gear and making my way up the beach, found very large, black bear tracks near my tent. I had my rifle with me on that first trip to the tent. It was a .38/40, not really a bear gun, but it carried 13 cartridges. It was some protection and I was a good shot.

I could smell the bear, for he had been all around the vicinity of the tent but I couldn’t see him. Suddenly, there he was; thankfully about 300 yards up toward the head of the bay slowly ambling toward the river. He was a very large black bear and I was glad to see him at such a distance. We probably arrived just in time to keep him from entering the tent and eating my supplies.

Once bears get accustomed to human food they can become a great nuisance and when they start to break and enter they eventually must be removed, by one manner or another.

I pulled my skiff out to deeper water on the haulback and then went back to

the tent for some food. Frankly, I don’t remember what I ate but there was a

lot of it. The Coleman stove warmed the tent a bit and I cleaned up my

rifle as best I could. My sleeping bag was rather soggy after all the rain but I took off my raingear, my hip boots and my sou’wester and got into it and slept the clock around.

Part V

When I woke I was hungry again and I ate again. Then I went to the beach and gathered up my laundry. The storm had finally blown itself out and the rain had let up. Pigot Bay was very calm indeed. Having eaten my fill again I decided to take my wet sleeping bag and a change of clothes up to the R&R cabin at the head of the bay. I filled the gas can and took my fishing rod and my single-shot 20-gauge shotgun, rather than my rifle, which I had disassembled for cleaning.

Motoring up to the river in the calm bay was a pleasure, even with the handicapped engine. It was probably midday when I arrived. I was planning on building a fire and drying my wet sleeping bag above the big old woodstove against the wall. I was not prepared for the mess I found within. A back bear had entered the small cabin through the window on the north end of the building. The window had been pushed open at the top, had fallen inward, but the glass had not broken. I set it back in place to warm the cabin. The window was at a right angle to the door, which was on the northeast side of the building. A small porch with two steps lay in front of the door, to gain access to the eight-by-twenty-foot cabin on log skids.

It was hard to believe what that big bear had done to the large canned goods supply which had been so neatly shelved. Canned peaches, pears, apricots, meats and vegetables of every sort lay scattered on the cabin floor. He had chewed every single can in the cabin and had emptied every canister holding sugar, flour and pancake mix. This looked like a professional job.

I built a fire in the woodstove, turned my sleeping bag inside out and proceeded to dry it and my other wet gear. For the next several hours I cleaned cans and debris out of the cabin. I hadn’t really planned to stay the night but it was so warm and cozy that I decided to do so. There must have been 100 chewed cans and boxes that I put into a pile outside for disposal on the following day.

I went down to the river and caught a Dolly Varden trout for supper. Before going to bed I stood the little shotgun in the corner, between the window and the door. I had only one rifled slug as ammunition and a few birdshot for reserve, if needed. I reminded myself that the”B” in birdshot is for Bird, not Bear. With food in my stomach and the warmth of a fire I went to bed early, thinking of the violent storm of yesterday and how calm it was right now.

It must have been just before daylight that I was wakened by a loud crunching noise outside by the pile of cans. The bear was back, revisiting the scene of the crime, as they always do. Having no flashlight I was loathe to opening the door, so I crept quietly to the window. It was darker inside the little cabin than outside. The cabin seemed to be getting smaller all the time.

I pressed my nose against the window as my eyes began to adjust to the darkness Suddenly, the window moved against my nose and adrenalin surged through my body. The face of a very large black bear was on the other side of the glass just opposite my nose. The hairs on the back of my neck rose in unison and I had a moment of sheer terror! There was not room in this tiny cabin for the two of us and the brute was intent on coming in again!

I felt the window move against my nose again, and without a conscious thought, I picked up the 20-gauge. Holding it by the pistol grip in my right hand, I swiftly opened the door, swung the gun around the corner of the cabin, shoved the muzzle virtually against the bears shoulder as he stood at the window and fired. Without waiting to see the bear’s reaction I quickly stepped back into the darkness of the cabin, bolted the door, and reloaded the shotgun with a birdshot cartridge.

I assumed that the bear would flee to the brush. However, I had made several wrong assumptions the past few days and the question came to mind: Could the shock and sound of the shotgun blast have caused the hard-hit bear to spring forward, through the window, into the cabin, and was now with me?

I had an empty feeling in the pit of my stomach, that was not hunger. Had the noise of the shotgun covered the sound of breaking glass as the window fell into the cabin? Had I retreated to the darkness of the cabin, as the mortally wounded bear entered through the window? Worse than a bear and I together in that small cabin, would have been a wounded bear and I.

As daylight began to show the cabin’s interior more clearly I could see that I was alone and was greatly relieved. When I did go outside, I found the bear had only gone about 30 feet and died quickly, shot though the heart.

I took no pleasure in killing that bear, though I was thankful that we had not spent the night together in that little cabin. The bear was a large male, probably over 400 pounds He was too heavy for me to drag, so I fashioned levers to move him to the water’s edge and into the bay,

We patrolmen were not up here to kill wildlife but who would I report the incident to and who would have removed the intruder? I was the highest ranking wildlife officer within 60 miles. So, it was done. As usual, it was the field man that had to do it.

These were the Territory days of Alaska. Without any means of communication with others, those spontaneous decisions, without benefit of permit or review, were sometimes accompanied by life-threatening consequences. I will always remember that great bear’s face and the press of the glass against my nose.

SE Alaska’s awesome, melting glaciers

Cruise passengers get close to Marjorie Glacier. (Bill Ryan)

SOUTHEAST ALASKA’S CALVING GLACIERS are an apt symbol of nature’s response to a warming environment. Glacier Bay also holds a historic lesson about the cataclysmic consequences rapid climate change can have for human communities.

It is a rare privilege to visit the icy waters of Glacier Bay National Park. Only a few boats at a time are permitted to view the towering ice walls where glaciers come down from majestic mountains to the bay. Access is limited, especially to protect the bay’s multitudinous humpback whales.

Marjorie Glacier is constantly calving (Bill Ryan)

Brother Andy had secured a precious permit, allowing us to come from Juneau and enter the park. We took Osprey up to the park’s two grandest glaciers, staying far enough away to avoid being swamped when large ice chunks splashed into the frigid water, and gently weaving our way through the ice bits floating all around. Our little boat shared one inlet with a colossal cruise ship, and the other with a busy whale and seals floating on ice.

Tlingit totem at Bartlett Cove (Bill Ryan)

Bill Ryan catches a glacier ice chunk for the cooler

Heading south, we were suddenly surrounded by a half dozen feeding humpbacks. We spent a lazy afternoon anchored in a otherwise quiet cove as a couple of noisy whales blowed and splashed about.

Johns Hopkins Inlet (Bill Ryan)

As night fell, an urgent radio call interrupted our reverie. A small fishing boat with an elderly crew member had run out of fuel just a few miles away. No one else was nearby. We pulled anchor and sped toward a distant spotlight to deliver the one can of gas we had onboard to the relieved fishermen.

Across Icy Strait from the park, we docked at Hoonah, a mostly Tlingit town now a stop for thousands of cruise ship passengers. Here we learned from locals about the catastrophe that befell their ancestors who dwelled around Glacier Bay until 1754. Two exceptionally cold years—possibly due to distant volcanic eruptions that darkened the sky—produced a huge, fast-moving glacier that filled the entire bay. The few people who survived were forced to flee south to a place they called Xunaa, meaning safe from the north wind. Descendants speak reverently about the homeland few ever get to visit.

Circling gulls follow humpback’s progress (Bill Ryan)

Humpback blows before Gilman Glacier (Bill Ryan)

Between stops in wilderness anchorages we visited a couple of very friendly towns. Tiny Tenakee Springs offered a mineral bath and a cafe proprietor offering cinnamon rolls and helpful local boating knowledge. In Kake, the ex-minor league ballplayer who brought us fuel drove us around, pointing out black bears feasting on salmon in a creek running through town.

Tenakee Hot Springs

We lucked out with an unexpected string of sunny, warm days as we motored south through wild big islands. At Kuiu Island we kayaked with herons and loons. After cautiously transversing the aptly named Rocky Pass in Kuiu Strait, we spotted an orca heading down Sumner Strait.

Gulls monitor traffic in John’s Hopkins Inlet (Bill Ryan)

Petersburg Harbor

From Petersburg we ventured up to LeConte Glacier, the Western Hemisphere’s southern most tidewater glacier. Up close, the face cracked and boomed as pieces fell off. The giant creature-like shapes of blue ice floating outside the inlet were captivating.

Andy dropped me off in Wrangell and took on his next crew member eager to experience Alaska’s awesomeness from the water.

Humpback quartet in Glacier Bay. (Bill Ryan)

Teamwork (Bill Ryan)

Bald eagle over Tarr Inlet (Bill Ryan)

Sea otters float on their backs to eat (Bill Ryan)

Orca swims alongside us in Sumner Strait (Bill Ryan)

Kayakers in Tarr Inlet. (Bill Ryan)

Ice creatures guard LeConte glacier (Bill Ryan)

LeConte glacier (Bill Ryan)

Endangered species: Alaska salmon fishers

PINK SALMON WERE JUMPING in the harbor as purse seiners and drift gillnet boats streamed out of Juneau’s Auke Bay last night for a short net-fishing opening. It was easy to wonder if I was witnessing the end of an era.

Due in part to oversupply and overwhelming competition from factory fish farmers, commercial salmon fishers across the state of Alaska are being paid all-time low prices for their catches. And other factors—such as an environmental lawsuit seeking an outright ban on the state’s king salmon troll fishery—are causing many captains to reconsider whether fishing remains a viable means of supporting their families.

Osprey tied up at Float D, in Auke Bay’s Slatter Harbor, adjacent to the freezer-equipped troller Searcher

Although a federal appeals court earlier this month granted trollers an at-least-temporary reprieve—issuing a stay on a lower court’s order that would have closed the king salmon fishery indefinitely—the skipper of the big freezer-equipped troller Searcher, tied up next to Osprey, told me the price being offered for his top-quality kings is so low he can’t afford to sell his catch.

It’s complicated.

Craig Medred, dean of Alaska outdoor writers, argues (I think simplistically) that the decline of the state’s once-booming salmon industry can be boiled down to one word: “Greed.” Citing a 2007 World Wildlife Federation report, Medred says the successes of Alaska salmon fishing 40 years ago—“the now unbelievable price of $7.39 per pound being paid for salmon at the start of the 1980s”—persuaded Norwegian entrepreneurs to invest heavily in fish farming. In the early 1980s, Medred writes, salmon farming was “a two-bit business with high production costs.” But by 2021, “farmed salmon accounted for 79.7 percent of global salmon production, and the trend toward farmed salmon and away from wild salmon is continuing as the farmers become ever more efficient.”

Bad prices and changing industry economics aside, however, Auke Bay was full of fishing boats this week, preparing for the four-day opening:

Gillnetters on Float D

Two gillnetters, a purse seiner, and a luxury yacht

An old (maybe older than me) but still active salmon troller

The 87-foot Marine Protector Class Coast Guard Cutter Reef Shark. Before being assigned to Juneau, the ship was responsible for the seizure of millions of dollars worth of drugs, in the Caribbean

Off the charts—literally

MARY RYAN AND HER BROTHER ANDY (that’s me), were staring at the nautical chart of the Endicott Arm fjord as we approached the big Dawes tidewater glacier. For the past two miles the chart showed there should be solid glacial ice under Osprey’s hull. Instead, there was a water depth of 400 feet, the murky surface littered with hundreds of “bergy bits” and “growlers,” through which we carefully threaded our way to get close to the massive glacier. I couldn’t tell when the electronic chart of Endicott Arm was last updated, but it couldn’t have been all that long ago; and the evidence of a warming planet was on full display.

The electronic chart says there’s a glacier here, but this is now deep water

The day before, we had waited for high slack tide and made our way into Ford’s Terror, a glacial bowl noted for its fast, powerful tidal currents. In 1899 American naval crewman Ford made the mistake of taking a rowboat into the current and was trapped for six hours in the mountain bowl that came to bear his name. We avoided a repeat of Ford’s terrifying experience but as the sun set our lovely anchorage was suddenly swarmed with savage biting black flies. These horrid little blighters—small enough to squeeze through Osprey’s window screens—are my absolutely least favorite thing about boating in British Columbia and Alaska. One night in Ford’s Terror was enough for us, and we made a hasty retreat the next morning.

On our way out of Endicott Arm, heading north to Juneau, we were treated to sightings of a humpback whale wildly splashing its enormous foreflippers in the current; to a lone male brown bear scavenging along the shoreline of the Snettisham Peninsula; and to weirdly shaped bergy bits floating out into the shipping lanes of Stephens Passage.

From Petersburg to Juneau is about 107 nautical miles, the longest stretch without a fueling station Osprey will face this summer. We were carrying extra gas, but as we made our way north along the length of the nation’s seventh largest island (Admiralty Island, 1,646 square miles, slightly smaller than the state of Delaware) we were running on fumes. Next time we’ll go slower, save gas.

Mary and Andy preparing to leave Petersburg for points north (Bob CJ)

View from our anchorage in Ford’s Terror (Mary Susan Ryan)

Kayaking at Ford’s Terror

View at the start of our “off the chart” day (Mary Susan Ryan)

Mary studying our route to the Dawes Glacier

Waterfall deep in Endicott Arm (Mary Susan Ryan)

Waterfall deep in Endicott Arm (Mary Susan Ryan)

Striated rock face at Dawes Glacier (Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

… and bergy bits in all directions (Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

Islands of vegetation seem to float out from a Dawes Glacier rock face

(Mary Susan Ryan)

Dawes Glacier from a safe distance (Mary Susan Ryan)

A little bit closer now (Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

Whale show (Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

Bear show (Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

Canis horribilis (Marla Williams)

Pleasure boat on the tidal grid at Harris Harbor, Juneau, for repairs

Osprey at the transient moorage dock, Harris Harbor

Alpenglow on a cruise ship in Juneau Harbor, at twilight

Misty Fjords to Petersburg

BIG BROWN BEARS happily grazing like cattle on lush green grass along the shore in Misty Fjords National Monument. A harbor crammed with enormous cruise ships, and hundreds of tourists milling about the streets of Ketchikan. An insane 4th of July fireworks battle—featuring armored boats firing flamethrowers—at the normally laid back logging town of Thorne Bay. An aborted attempt to navigate the mudflats of aptly named Dry Strait on a falling tide. Andy’s and Bob CJ’s adventures during their 1,300-mile trip from Kenmore, Wash. to Petersburg, Alaska were too numerous to count. But we took some pictures:

A contrast in traveling styles—Osprey cruising Ketchikan (Bob CJ)

Chart watching is a constant activity while underway (Bob CJ)

Kayaking the shores of Walker Cove, Kenai Fjords National Monument (Bob CJ)

Chanced upon this sow brown bear and cub while kayaking magical Misty Fjords (Bob CJ)

Watching him graze on the lush shoreline grass, we nicknamed this male brown bear “Blondie” (Andy Ryan)

This massive rock face at Punchbowl Cove, Misty Fjords, is reminiscent of Yosemite—if one could boat through Yosemite! (Bob CJ)

BW of the entrance to Walker Cove, near Behm Strait. (Bob CJ)

Is the sky trying to tell us something about tomorrow’s weather? (Andy Ryan)

Supper aboard Osprey at Thorne Bay (Bob CJ)

Bob CJ navigating Wrangell Narrows, en route to Petersburg

Bob CJ navigating Wrangell Narrows, en route to Petersburg

Norwegian Rosemaling in Petersburg (Mary Susan Ryan)

Dinner at Inga’s Galley seafood restaurant in Petersburg with our friends Sally, Sue and Rocky

Bob and Andy at the end of their epic 1,300-mile journey (Mary Susan Ryan)

Postcard from Ketchikan

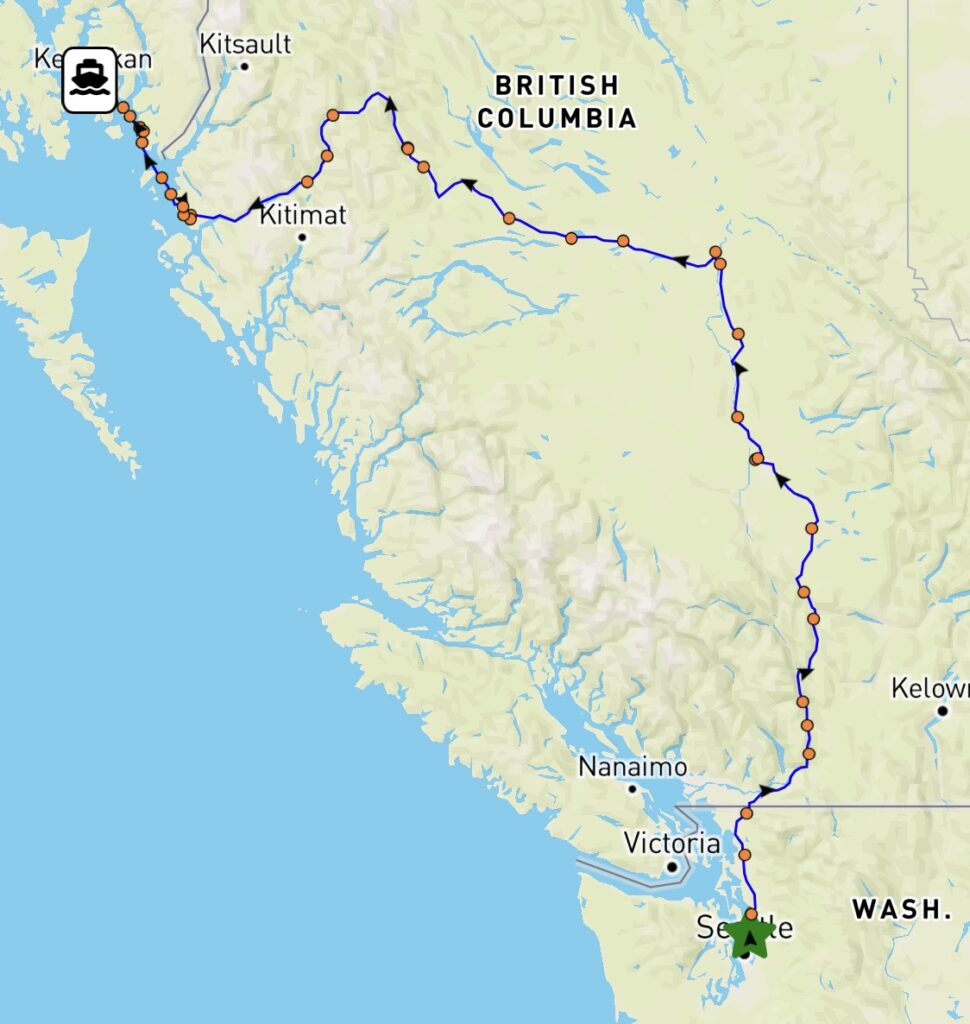

POSTCARD FROM KETCHIKAN. Day six of our voyage, and we’re getting underway again—with 1,100 land and sea miles already under our belts. Our trip has taken us hundreds of miles along British Columbia’s mighty Fraser and Skeena rivers, with Osprey in tow behind my stalwart Ford Explorer to our launching point at Port Edward, B.C. From there it was another 100 nautical miles to Ketchikan, where we have been chilling for the past two days.

Kenmore to Ketchikan

(Bob CJ)

Carving by Nathan Jackson at Cape Fox Lodge, Ketchikan (Bob CJ)

View from anchorage at Foggy Bay, Alaska (Bob CJ)

Bar Harbor Marina, Ketchikan (Bob CJ)

Osprey north to Alaska

THE TOPS OF A SUBMERGED RANGE of steep coastal mountains form the 1,100 islands of Southeast Alaska’s Alexander Archipelago, ancestral home to the Tlingit and Kaigani Haida people and citadel of North America’s most charismatic species. Starting in late June, Osprey, her captain, and five crew members (sequentially) will spend nine weeks exploring this magnificent realm. If we’re lucky we may get a glimpse of Canis lupus ligoni, the highly threatened Alexander Archipelago”Islands Wolf.”

Source: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

And almost certainly, as we cruise through deep glacial fjords along the length of the 300-mile-long archipelago, we will see brown bears, sea lions, eagles, sea otters, killer whales, humpback whales, Sitka black-tailed deer … and, just imagine, Northern Flying Squirrels.

Osprey starts her journey north June 25, with a 1,000-mile trailer ride from Everett, WA to Port Edward, BC, where she will be launched. From there, it’s about 100 miles north, across windy Dixon Entrance, to Ketchikan, Alaska’s most southerly city.

Here’s a link to our itinerary, and a map of our intended route.

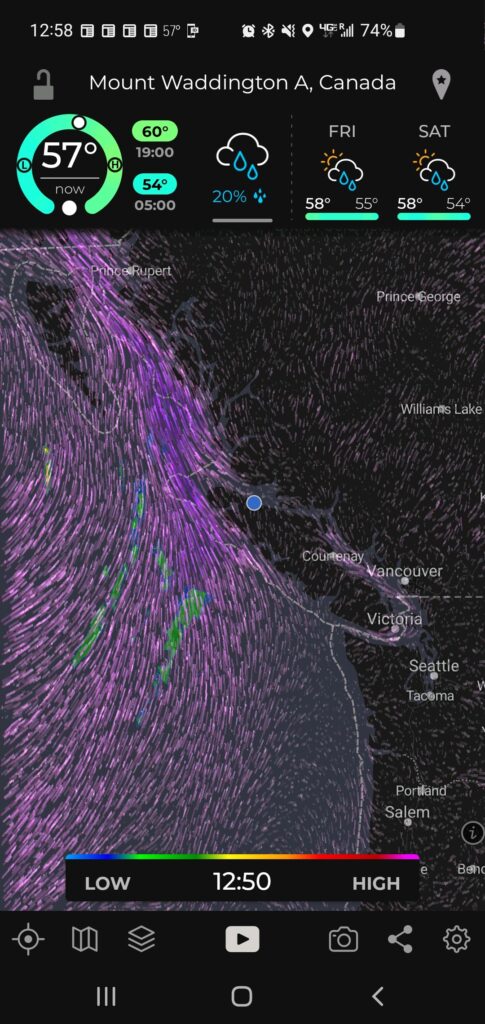

Go/no go decision at Port McNeill

Red indicates areas with gale warnings

UNSEASONABLY BAD WEATHER off Vancouver Island’s Cape Scott, and from the tip of the island down the northwest coast, has been the norm for the past two weeks. For a few hours Friday it looked as though there might be a two-day weather window that would allow Osprey to make a 112-mile dash around the cape to the nearest port, Winter Harbour. I got up at 4 a.m. Saturday, started the engines … and then read the updated weather report:

The Marine Weather Forecast In Detail:

Environment Canada Forecast Issued: 400 AM PST

GALE WARNING IN EFFECT

Winds…Wind Northwest 10 To 20 Knots Except Northwest 20 To 30 South Of The Brooks Peninsula. Wind Becoming Westerly 15 Early This Morning Then Increasing To Northwest 15 To 25 Sunday Morning Except Northwest 20 To 30 South Of The Brooks Peninsula Sunday Morning And Afternoon And Northwest 30 To 35 South Of The Brooks Peninsula Tuesday Late In The Day.

Waves … Seas 1 To 2 Metres Building To 2 To 3 Sunday Evening.

Monday … Winds Northwest 20 To 30 Knots Becoming Northwest 25 To 35 Late In The Day.

Tuesday … Winds Northwest 20 To 30 Knots Becoming Northwest 25 To 35 Late In The Day.

Wednesday … Winds Northwest 20 To 30 Knots Becoming Northwest 25 To 35 Late In The Day.

In plain U.S. English that means sustained winds as high as 40 miles per hour, with wave heights up to 10 feet.

My friend Harvey sent me a picture of what the wind was doing along my planned route. He wrote, “Andy. Here’s the weather. Icky.”

Gale force southwest winds off Vancouver Island coast. Blue dot shows Osprey’s location

So, aaack! As a Kipling character lamented, in The Elephant’s Child, “This is too buch for be!” No need to intentionally sail into a perfect storm, and I was running out of time to wait it out.

I turned Osprey around and headed south, back down the island’s east coast— where the weather was surprisingly calm. Running with radar in a little fog at the north end of often-scary Johnstone Strait, but clearer as I went further south at close to wide open throttle, 25 miles per hour, now suddenly very eager to get home. All the way down Johnstone Strait and through turbulent Seymour Narrows, with the current running at 9 mph against me. No problem for my agile little boat. Refueling at Campbell River, past Comox and Nanaimo, to a pretty cove south of Dent Rapids, where I anchored in 10 feet of water, after a 203-mile Osprey-record-shattering run. Whew! Madness.

Yesterday, Sunday, an easy 70 more miles back to our starting point, Cap Sante Marina, after a wireless check-in with U.S. Customs, using the handy CBP Roam app. The marina assigned me to Slip 66.

As you can see, slip 65 was taken. A few minutes later, one of the seals gave birth—on the dock! She growled at anyone who came close to her new baby.

That concludes this 889-mile adventure. Shorter than I had hoped for, but tremendously rewarding, and certainly safer than what the weather gods had planned for me if I’d tried to go around the west side of the island.

Health, scheduling, and finances permitting, I’ll give it another try, next year.

As a famous pig said, frequently, “Th-Th-The, Th-Th-The, Th-Th … That’s all, folks!”

Afloat in the misty isles

White sand beach in Burdwood Group, Broughton Islands (Julie Burman)

JULIE AND I MOTORED INTO northeast Vancouver Island’s Port McNeill after a two-week, 673-mile maritime road trip that took us from the densely populated Puget Sound region to the glorious reaches of British Columbia’s remote Desolation Sound and Broughton Archipelago. It was rejuvenating to get out of Megalopolis, if only for a while. I believe Ms. Burman (the best of sports) and I remain pals—a remarkable accomplishment for two people shoe-horned for 15 days into a boat cabin the size of a tiny jail cell, much of the time in drizzle and fog.

Here’s a selection of Julie’s photos from a most memorable voyage:

Basking on the bow (Julie Burman)

Asiatic lilies, Lund

Entering Desolation Sound (Julie Burman)

Toba Inlet, Desolation Sound (Julie Burman)

Coast Range glaciers, from Toba Inlet (Julie Burman)

Lacy Falls, in Tribune Channel, Broughton Archipeligo (Julie Burman)

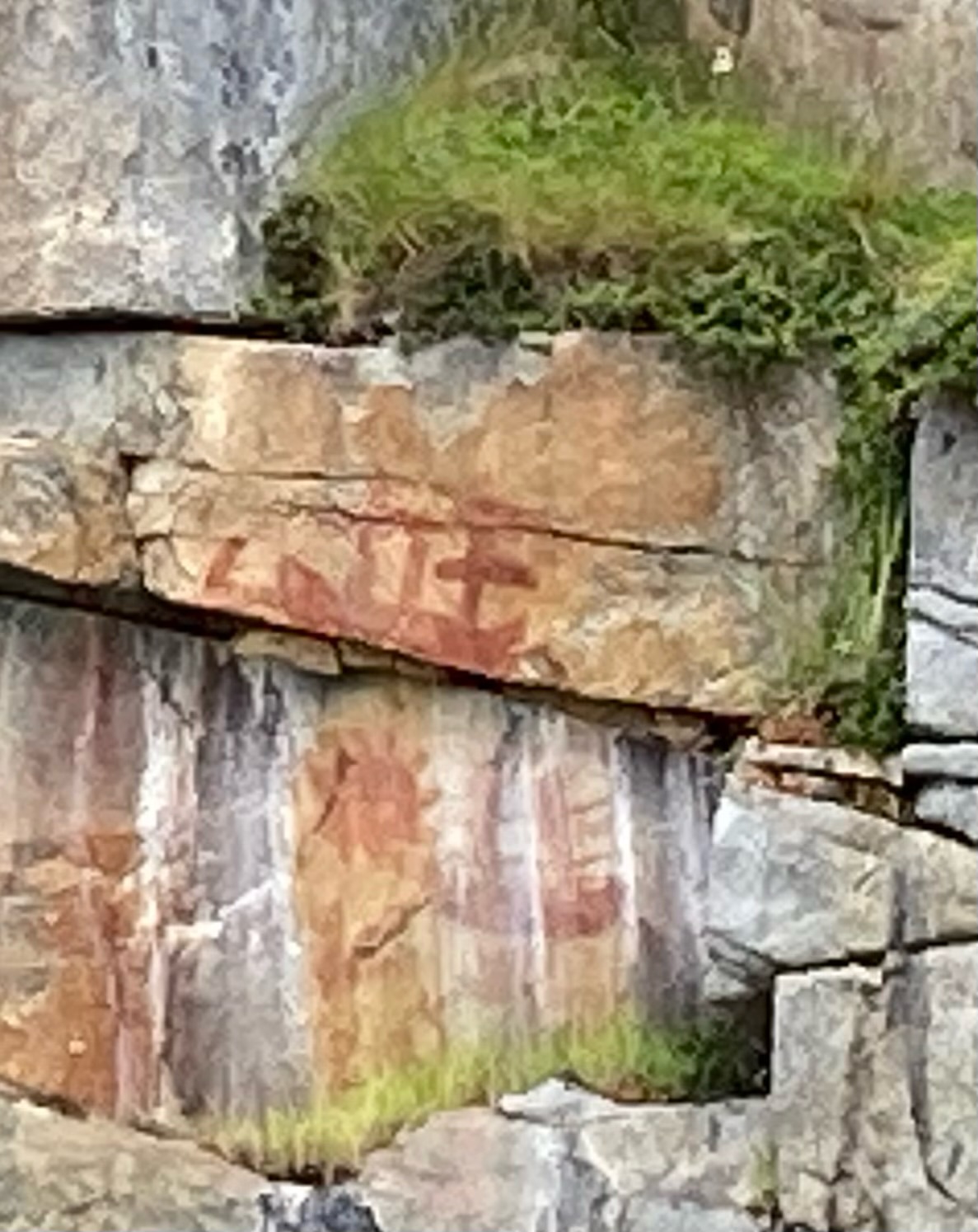

Pictograph of sailing ships, near historic First Nations village of Karlukwees, along Beware Passage (Julie Burman)

Paddle board campers on the edge of Queen Charlotte Strait (Julie Burman)

Entrance to the historic village of Mimkwamlis (Village Island), which was occupied until 1972 by the Mama̱liliḵa̱la First Nation. (Julie Burman)

Ruins on Village Island (Julie Burman)

Village Island (Julie Burman)

At Village Island (Julie Burman)

‘Namgis original burial grounds and totems, Alert Bay (Julie Burman)

Giant halibut-man carved by Stephen Bruce, 1995, Alert Bay (Julie Burman)

Alert Bay net shed (Julie Burman)

Buster Islet, among the Fog Islets, Broughton Archipelago (Julie Burman)

Julie Burman, at Sullivan Bay Marina