Archive for August 2019

Bad news for wild fish

Osprey passing an open net-pen salmon farm in the Broughton Islands this summer (Harvey Hochstetter)

DON’T BUY FARMED SALMON—and consider boycotting stores that sell it. Ask your friends to do the same.

As I’ve made my way along the British Columbia coast this summer, I have been struck by the number of floating fish factories—open net-pens containing hundreds of thousands of genetically altered Atlantic salmon—infesting these waters.

There is no rational reason I can see for the Canadian government to allow these ugly insults to the planet, which pose a very real threat to the five species of Pacific salmon that have sustained coastal people (and orcas and bears) for thousands of years. Salmon are the very soul of the North Pacific coast.

British Columbia’s neighbors, Alaska and Washington state, have implemented outright bans on net-pen salmon farming.

Bumper sticker seen at Alert Bay

The B.C. salmon farms, over 100 of them, are located along migration routes for native fish stocks, and there is conclusive scientific evidence that fish farms provide ideal breeding conditions for parasitic sea lice. The lice attach themselves to juvenile native salmon; it takes only two or three lice to kill a young fish.

According to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, “Wild salmon close to fish farms are 73 times more likely to suffer lethal sea lice than juveniles not adjacent to fish farms. A fish farm can also elevate the rate of sea lice infestation in salmon up to 40 miles from their pens. Sea lice can survive for about 3 weeks off their host—making transfer from farmed to wild salmon possible.”

Worse than sea lice, perhaps, up to 95 percent of open net-pen Atlantic salmon in British Columbia are infected with Piscine Reovirus, a highly contagious disease which can cause heart and skeletal inflammation in salmon. The strain of the virus found in B.C. fish farms is believed to have originated in Norway, introduced to the environment along with the farmed fish.

And yet, inexplicably, the Canadian government has pressed for regulations which would specifically allow disease-infected salmon to be introduced into B.C. net pens. Opponents of net-pen farms have been met with stonewalling in their attempts to obtain correspondence between industry and government scientists.

There are signs like this in villages up and down the B.C. coast. This one’s in Alert Bay

Salmon farming is big business, and you have to wonder if someone is getting paid off.

The many First Nations people I have spoken with along the coast this summer have expressed strong opposition to open net-pen salmon farming, which they see as a direct threat to their way of life. Salmon are at the heart of native spiritual and cultural practices, and are the most important subsistence resource for people who make their livings from the sea.

As of this date, Jonathan Wilkinson, Canadian minister of fisheries and oceans (along with Canada’s Coast Guard), has been unresponsive to their concerns about the hazards of net-pen salmon farming, local people have told me.

So before you buy that salmon filet, check where it came from. If it doesn’t say wild salmon, or if it says “Atlantic salmon,” don’t even think about buying it. You’ll be doing Mother Earth a favor; and besides, farmed salmon—treated throughout their lives with pesticides and antibiotics—doesn’t taste good.

Here are some photos Harvey took as we passed yet another net-pen operation in the Broughton Islands this week:

Two Harveys

Harvey Hochstetter and Sleepy C

MY FRIEND HARVEY HAS JOINED ME in Port McNeill. Harvey is another C-Dory owner, and for the next couple of weeks we’ll be buddy-boating through the Broughton Islands archipelago, at the eastern end of Queen Charlotte Strait.

Harvey brought Sleepy C up from Sequim, Wash. two weeks ago. Since then, he has been helping the owner of the Port Harvey (no relation) Marina, Gail Cambridge, get her possessions packed up for her move back to Alberta. Gail’s husband George died suddenly, a year ago, and Gail can’t run the marina by herself.

Harvey had come to know the Cambridges over a couple of summers cruising in the Broughtons; he became a more active supporter of the little mom and pop marina last year when a local man sought to have part of the bay rezoned, to permit the operation of a noisy, ugly shipyard directly across from the marina.

The Cambridges believed the industrial operation would destroy the solitude and quiet of their beautiful little cove. And their business along with it.

Port Harvey Marina

I followed the rezoning process from afar, reading local newspaper stories online and listening to first-hand accounts from Harvey, who drove up to Port McNeil to participate in the hearings. For a number of years I worked as a newspaper reporter, covering local, state and federal government—and from what I could see, in the pro-development environment that seems to prevail up here, the deck was stacked against the Cambridges. They never had a chance.

At one point, the marina’s dock sank, for no apparent reason. Harvey is convinced it had to have been sabotage.

On May 15, 2018, despite considerable local opposition, the Regional District of Mount Waddington adopted Bylaw 895, rezoning the Cambridges’ neighbor’s land—from “rural” to “marine industrial.”

In a news release sent out after the Mount Waddington District’s decision, George Cambridge said he would appeal the ruling.

“An industrial scale marine repair and salvage business being operated at this location is incompatible with all other adjacent uses,” Cambridge wrote. He added that the regional district violated one of its own bylaws, “that no rezoning bylaw can be enacted that allows a new use that is incompatible with existing adjacent uses.”

The Cambridge family

George set up a GoFundMe page in an attempt to raise the estimated $80,000 cost of fighting the ruling … and then everything ended for the Cambridges and the Port Harvey Marina. Three months after the zoning decision, George died in his sleep of an apparent aneurism.

And so, for the past couple of weeks, Harvey and a small band of friends have been helping Gail Cambridge pack up the memories of a long, happy marriage. A water taxi was scheduled to take her away this week. Harvey and I have plans to stop off at the now vacated marina, for a last look, on our way back from the Broughtons.

Along the spirit bear coast

Great Bear Rainforest (Source: Mapbox Streets)

FROM THE TIME I CROSSED FROM ALASKA INTO CANADA, across wide Dixon Entrance, I was in the “Great Bear Rainforest.” The name, a public relations masterstroke, was coined in a San Francisco restaurant one night in the late 1990s by environmentalists working to protect one of the world’s last great temperate rainforests.

“We wanted people to hear the name and be mad as hell that anybody could turn it into toilet paper,” one of the activists wrote in a later memoir. Local residents reportedly were not consulted in the naming, but it appealed to the media and general public, and it stuck.

After a well-funded international campaign, targeting big lumber suppliers like Home Depot, the British Columbia government threw in the towel. In 2016 the prime minister declared 85 percent of the rainforest off limits to commercial logging. Depending on which website you want to believe, the protected area encompasses most coastal areas of northern B.C., and is between 12,000 and 22,000 square miles in size.

(If I’m getting any of is wrong, please let me know and I will make appropriate corrections.)

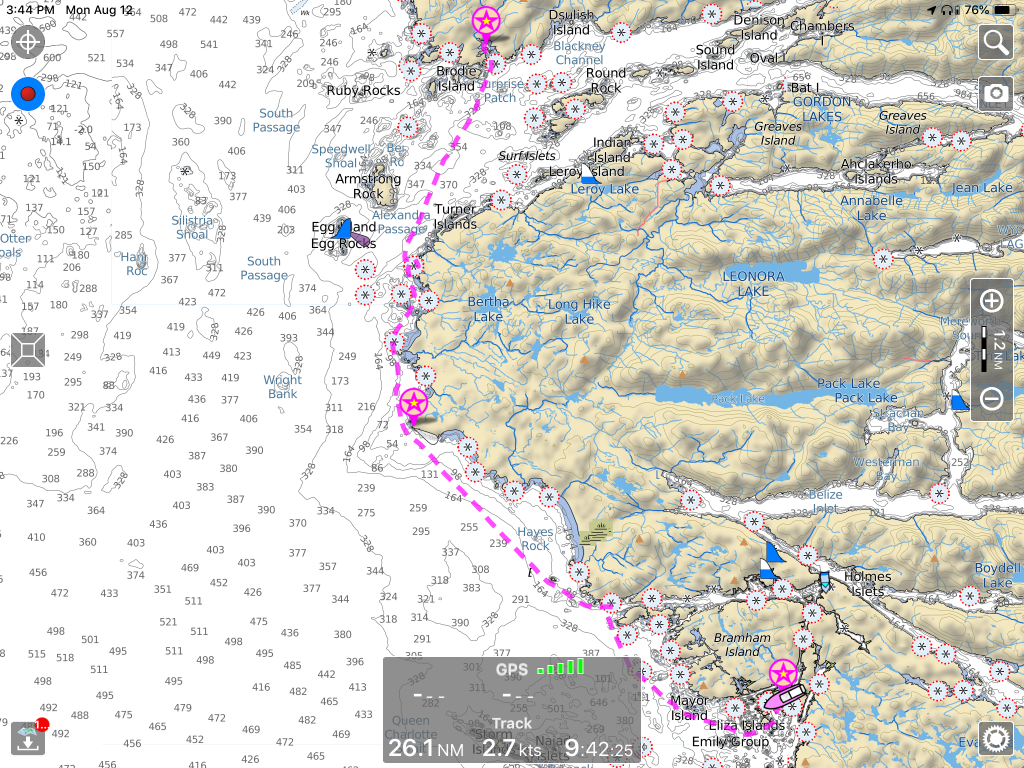

For the past two weeks, I have been slowly working my way down the outer coast of the rainforest, among dozens of archipelagos, hundreds of islands, with winding passages leading out to the ocean. Three of these outer islands are home to a rare subspecies of black bear—the Kermode or spirit bear (Ursus americanus kermodei). Ten to 20 percent of Kermode bears here—from 100 to 500 individuals—are white and I had hoped I might see a white spirit bear. But not this trip; I’ll have to come back.

This place is sacred to the indigenous people whose home it has been for thousands of years. And now it’s sacred to me.

Here’s some of what I saw along the way:

Prince Rupert docks in the fog, from Casey Cove

Kelp beds on outer coast reef

Fog rolls in on the outer coast

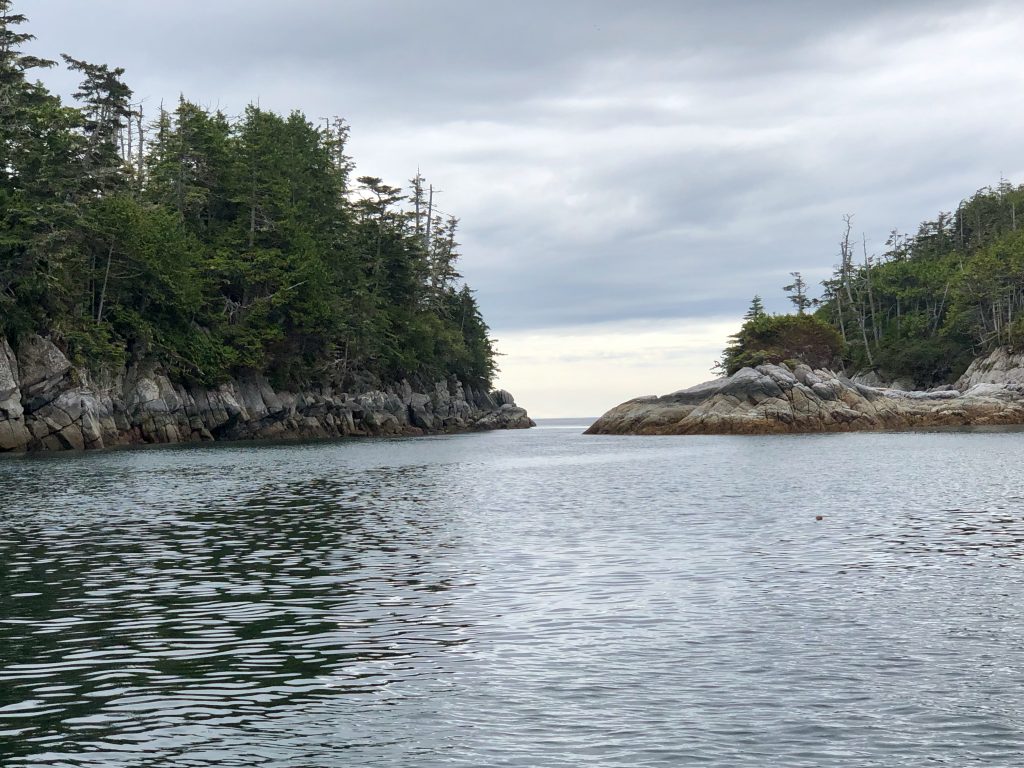

Island passages …

… around rocky points

Sometimes with the assistance of lighthouses …

Robb Point Light

Dryad Point Light, north of Bella Bella

A jellyfish nursery at Lewall Inlet (look very closely, there are several)

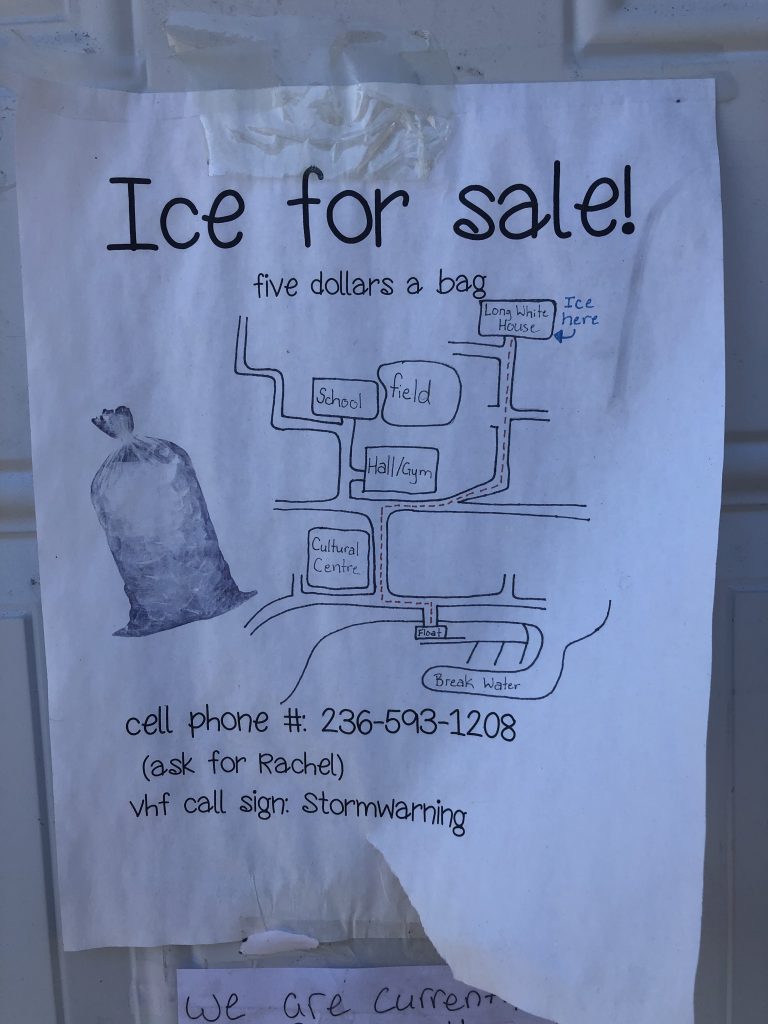

Ice for sale at Klemtu

Mt. Buxton, Calvert Island

Around Cape Caution

Cape Caution

And into Murray Labyrinth, where it was time for reflections.

Nathan and Dorica Jackson

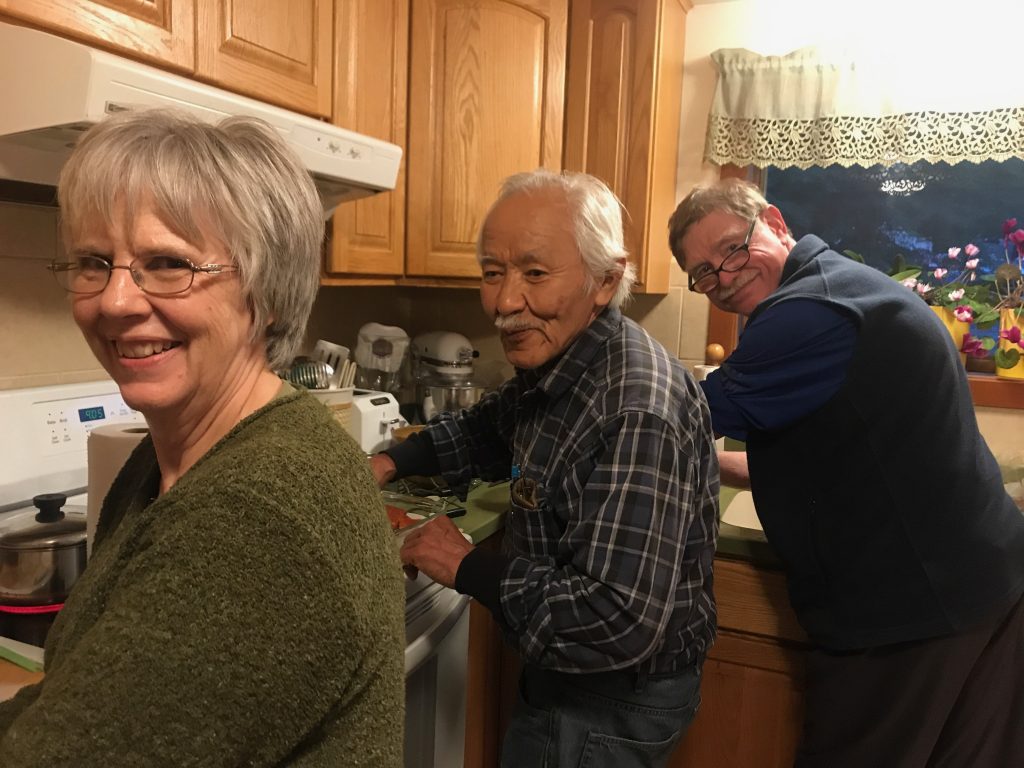

Dorica and Nathan Jackson (left) and Andy Ryan canning sockeye salmon in the Jacksons’ kitchen (Marla Williams)

MARLA AND I WERE HONORED TO HAVE DINNER, twice this week, with renowned Alaska Native artist Nathan Jackson and his wife, master weaver and textile artist Dorica Jackson. After our second dinner with the Jacksons, at their home near Ketchikan, we helped them put up a mess of sockeye salmon Nathan caught earlier in the week, purse seining.

If you’re not familiar with Nathan’s spectacular work, you can see examples of it, here.

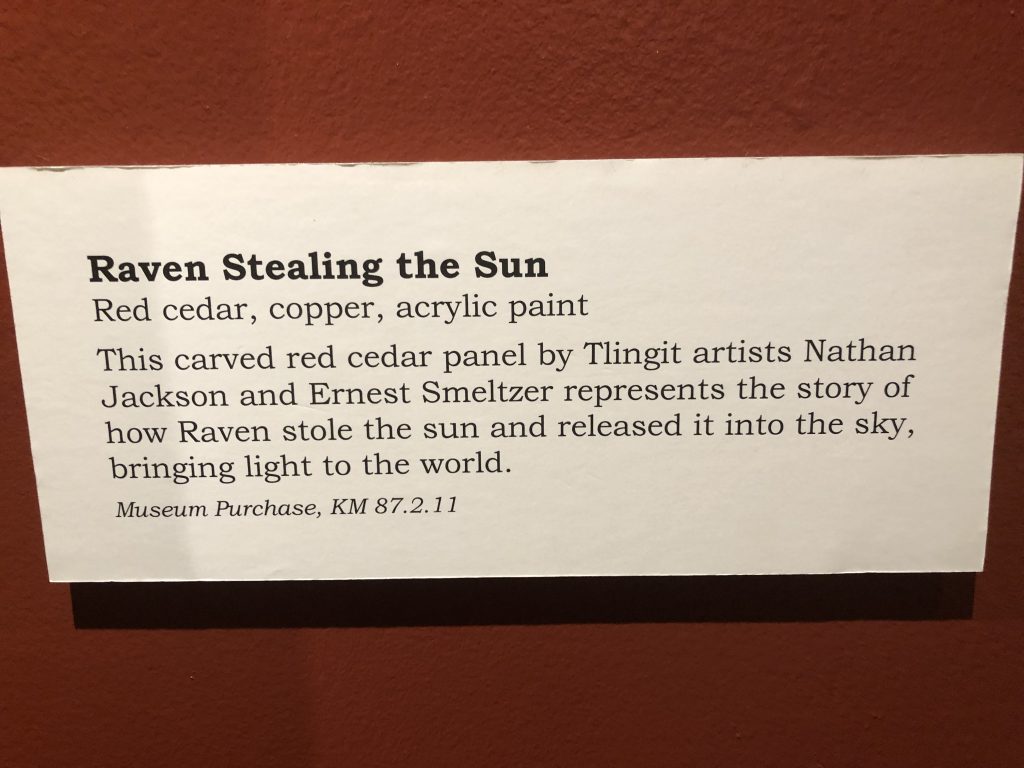

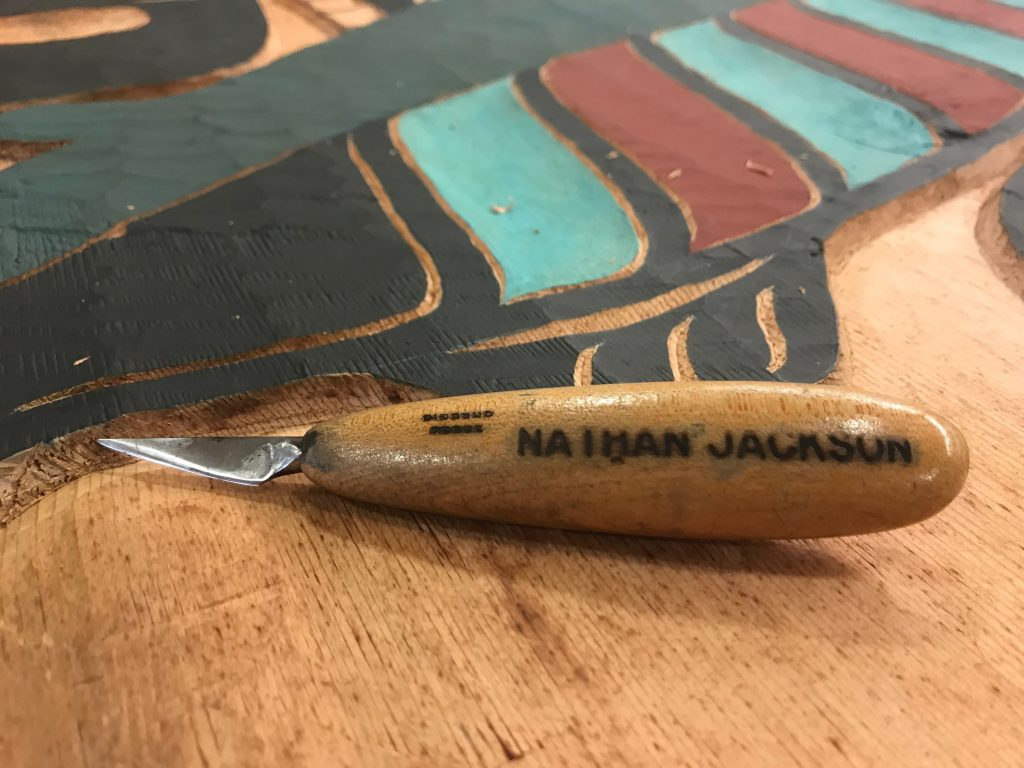

Raven Stealing the Sun, by Nathan Jackson and Ernest Smeltzer. Displayed at the Totem Heritage Center, Ketchikan

Nathan is the subject of a documentary by Marla, which begins airing this September on Alaska Public Media. The film is one in a six-part series, Magnetic North: The Alaskan Character.

Nathan Jackson airs Sept. 9, at 9:30, on Alaska Public Media. The series also includes films about:

—Clem Tillion

—Arliss Sturgulewski

—Roy Madsen

—Jacob Adams

—Bill Sheffield

The series is directed by Marla and edited by Kyle Seago. Funding provided by Rasmuson Foundation in association with the Alaska Humanities Forum.

For more information email akhf@akhf.org

Here are a few more photos from our visits with the Jacksons:

In Nathan’s workshop (Marla Williams)

Nathan, preparing sockeye for canning (Marla Williams)

Jars of salmon, ready for the pressure cooker (Marla Williams)

Dorica Jackson (Marla Williams)

Chilkat robe by Dorica, recently purchased by the Ketchikan Museums Department, with help from a Rasmuson Foundation grant. (Photo courtesy Ketchikan Museums)

Pit stop in Ketchikan

Ken Perry, Timber & Marine Supply, Ketchikan

ONE OF THE BIGGEST MISTAKES I MADE in preparing for this trip was neglecting to ask my outboard motor dealer if I would be able to get service on my way north for the new Tohatsu 50s I was considering buying.

Outboards require service every 100 hours, and I figured the trip would put at least 300 hours on the engines. I foolishly assumed that, because I had told the dealer I was buying the motors for a trip to Alaska, I would be able to get them serviced along the way.

Oops. It wasn’t until after I’d purchase the Tohatsus that I started trying to line up service appointments for the trip. I learned there are no Tohatsu dealers north of Nanaimo, on lower Vancouver Island.

Fortunately I was able to talk Ken Perry, owner of Timber & Marine Supply, into servicing the engines when I arrived in Ketchikan. But he gave me unceasing (but good-natured) grief about it every time I saw him. Ken asked for my dealer’s email address—for the purpose, I thought, of inquiring about Tohatsu parts.

Not exactly. Here’s what Ken wrote to my dealer:

“FYI for your future customers, why did you sell your customer (Andy Ryan) a pair of Tohatsu motors for his C Dory, knowing that he was going to travel through the inside passage of Alaska? There isn’t a single Tohatsu service center or dealer in any of Southeast Alaska. I also understand that you are a Honda Marine Dealer.

“There are multiple Honda Marine dealers in Canada and multiple Honda Marine dealers in S E Alaska. You can get a Honda outboard serviced in almost any town and no one will touch a Tohatsu Outboard. I’m just trying to save your future customers from heart ache and disapointment.

“Thank You Ken”

Ken’s shop did great work on my engines on my way north, and I stopped at his shop again on my way back south. After subjecting me to some mild ridicule, he serviced the engines—and said the Tohatsus and I would be welcomed back if I ever venture north again.

But Ken’s larger point is well taken: if the Tohatsus break down between here and Nanaimo, I may need a long, long tow home.