Posts by andy

Up in Smoke

(Kathy Curtis-Johnson)

KATHY C-J AND I WERE SPEEDING EAST on the Yellowhead Highway along the wide Skeena River, about 42 miles from Prince Rupert, heading for Seattle 1,000 miles away. We had pulled Osprey out of the salt water the day before, after spending a final night aboard, tied up at the Prince Rupert Rowing and Yacht Club. Kathy was reading The Milepost, looking for a good place to pull the boaterhome over for the night. Terrace, B.C. looked like a likely spot. Maybe Smithers.

British Columbia’s Yellowhead Highway, along the Skeena River (Source: GerthMichael/Wikipedia)

In the side mirror, I thought I saw a little smoke coming out of the tailpipe, and started looking for a place to pull over. But the busy highway was long and winding, with cars and trucks zipping by in either direction and only soft, skinny shoulders on each side. By the time I spotted a narrow strip with safe room to park, dense black smoke was pouring out of the engine. It looked like it was on fire. A message on the instrument panel said something was wrong with the transmission.

(Kathy Curtis-Johnson)

There was a trail of black, shiny transmission fluid on the pavement for some distance behind the Explorer; and although I have never personally experienced a blown tranny, there wasn’t much doubt that our forward progress was at an end for a while. A long while, as it turned out.

Fortunately, we had just enough cellphone bars to reach Marla, in Seattle—who was able to send Marty from Wayne’s Towing out the highway to rescue us. But there’s a labor shortage up here, and it will be close to a month before any Prince Rupert auto shop will be able to repair the Explorer; and—after a week of involuntary tourism in Prince Rupert—Kathy and I will be flying back to Seattle in the morning.

But I need to say this: I can’t think of a better place to be delayed by a blown tranny than beautiful Prince Rupert, with its kind, friendly, helpful folks. This is my fourth time here; I love this place.

Marty Johnson, who grabbed a friend, dropped everything and brought two trucks to rescue us (one for the Explorer, one for the boat) is a great example of the decent, generous people who inhabit this region. He even offered to let Kathy and me use his house while we arranged repairs for the Explorer. Thanks Marty.

With luck—and my luck has been mostly good on this fantastic two-month voyage—I’ll be back up here in mid-September, to pick up my repaired SUV, hook up the trailer and bring Osprey home.

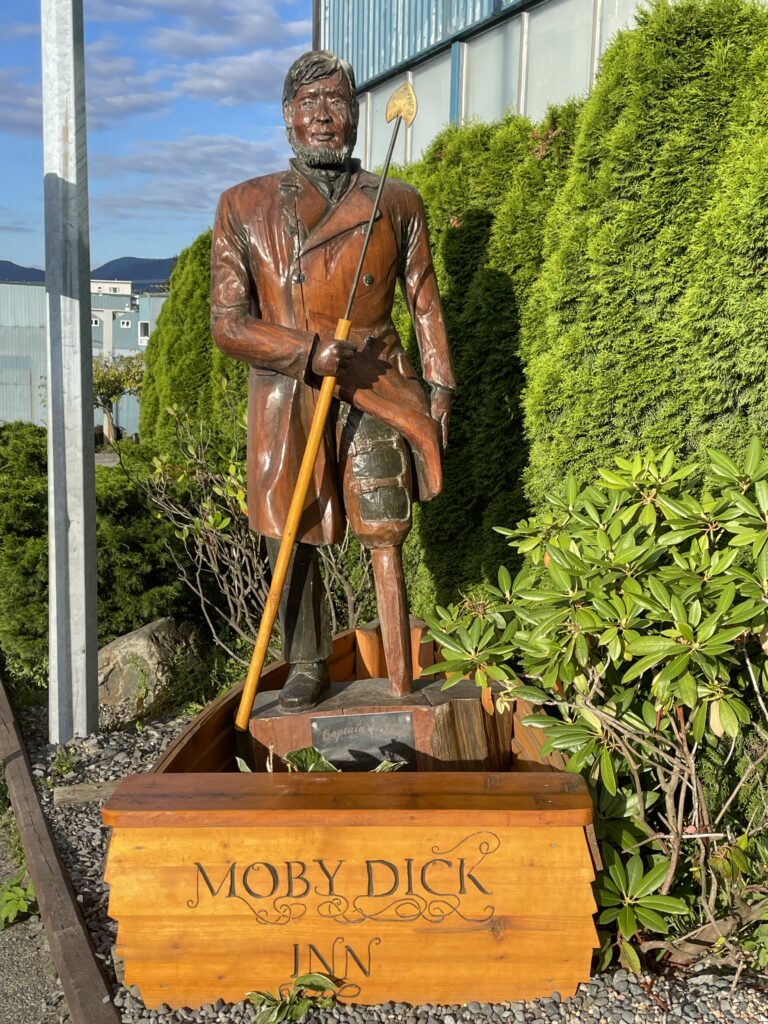

Capt. Ahab outside Prince Rupert’s Moby Dick Inn (Kathy Curtis-Johnson)

Two tugs and Osprey at commercial dock, Port Edward (Kathy Curtis-Johnson)

Gillnet on Port Edward commercial dock (Kathy Curtis-Johnson)

Mussels and barnacles on dock piling, Port Edward (Kathy Curtis-Johnson)

Endangered species: Alaska salmon fishers

PINK SALMON WERE JUMPING in the harbor as purse seiners and drift gillnet boats streamed out of Juneau’s Auke Bay last night for a short net-fishing opening. It was easy to wonder if I was witnessing the end of an era.

Due in part to oversupply and overwhelming competition from factory fish farmers, commercial salmon fishers across the state of Alaska are being paid all-time low prices for their catches. And other factors—such as an environmental lawsuit seeking an outright ban on the state’s king salmon troll fishery—are causing many captains to reconsider whether fishing remains a viable means of supporting their families.

Osprey tied up at Float D, in Auke Bay’s Slatter Harbor, adjacent to the freezer-equipped troller Searcher

Although a federal appeals court earlier this month granted trollers an at-least-temporary reprieve—issuing a stay on a lower court’s order that would have closed the king salmon fishery indefinitely—the skipper of the big freezer-equipped troller Searcher, tied up next to Osprey, told me the price being offered for his top-quality kings is so low he can’t afford to sell his catch.

It’s complicated.

Craig Medred, dean of Alaska outdoor writers, argues (I think simplistically) that the decline of the state’s once-booming salmon industry can be boiled down to one word: “Greed.” Citing a 2007 World Wildlife Federation report, Medred says the successes of Alaska salmon fishing 40 years ago—“the now unbelievable price of $7.39 per pound being paid for salmon at the start of the 1980s”—persuaded Norwegian entrepreneurs to invest heavily in fish farming. In the early 1980s, Medred writes, salmon farming was “a two-bit business with high production costs.” But by 2021, “farmed salmon accounted for 79.7 percent of global salmon production, and the trend toward farmed salmon and away from wild salmon is continuing as the farmers become ever more efficient.”

Bad prices and changing industry economics aside, however, Auke Bay was full of fishing boats this week, preparing for the four-day opening:

Gillnetters on Float D

Two gillnetters, a purse seiner, and a luxury yacht

An old (maybe older than me) but still active salmon troller

The 87-foot Marine Protector Class Coast Guard Cutter Reef Shark. Before being assigned to Juneau, the ship was responsible for the seizure of millions of dollars worth of drugs, in the Caribbean

Off the charts—literally

MARY RYAN AND HER BROTHER ANDY (that’s me), were staring at the nautical chart of the Endicott Arm fjord as we approached the big Dawes tidewater glacier. For the past two miles the chart showed there should be solid glacial ice under Osprey’s hull. Instead, there was a water depth of 400 feet, the murky surface littered with hundreds of “bergy bits” and “growlers,” through which we carefully threaded our way to get close to the massive glacier. I couldn’t tell when the electronic chart of Endicott Arm was last updated, but it couldn’t have been all that long ago; and the evidence of a warming planet was on full display.

The electronic chart says there’s a glacier here, but this is now deep water

The day before, we had waited for high slack tide and made our way into Ford’s Terror, a glacial bowl noted for its fast, powerful tidal currents. In 1899 American naval crewman Ford made the mistake of taking a rowboat into the current and was trapped for six hours in the mountain bowl that came to bear his name. We avoided a repeat of Ford’s terrifying experience but as the sun set our lovely anchorage was suddenly swarmed with savage biting black flies. These horrid little blighters—small enough to squeeze through Osprey’s window screens—are my absolutely least favorite thing about boating in British Columbia and Alaska. One night in Ford’s Terror was enough for us, and we made a hasty retreat the next morning.

On our way out of Endicott Arm, heading north to Juneau, we were treated to sightings of a humpback whale wildly splashing its enormous foreflippers in the current; to a lone male brown bear scavenging along the shoreline of the Snettisham Peninsula; and to weirdly shaped bergy bits floating out into the shipping lanes of Stephens Passage.

From Petersburg to Juneau is about 107 nautical miles, the longest stretch without a fueling station Osprey will face this summer. We were carrying extra gas, but as we made our way north along the length of the nation’s seventh largest island (Admiralty Island, 1,646 square miles, slightly smaller than the state of Delaware) we were running on fumes. Next time we’ll go slower, save gas.

Mary and Andy preparing to leave Petersburg for points north (Bob CJ)

View from our anchorage in Ford’s Terror (Mary Susan Ryan)

Kayaking at Ford’s Terror

View at the start of our “off the chart” day (Mary Susan Ryan)

Mary studying our route to the Dawes Glacier

Waterfall deep in Endicott Arm (Mary Susan Ryan)

Waterfall deep in Endicott Arm (Mary Susan Ryan)

Striated rock face at Dawes Glacier (Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

… and bergy bits in all directions (Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

Islands of vegetation seem to float out from a Dawes Glacier rock face

(Mary Susan Ryan)

Dawes Glacier from a safe distance (Mary Susan Ryan)

A little bit closer now (Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

Whale show (Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

Bear show (Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

(Mary Susan Ryan)

Canis horribilis (Marla Williams)

Pleasure boat on the tidal grid at Harris Harbor, Juneau, for repairs

Osprey at the transient moorage dock, Harris Harbor

Alpenglow on a cruise ship in Juneau Harbor, at twilight

Misty Fjords to Petersburg

BIG BROWN BEARS happily grazing like cattle on lush green grass along the shore in Misty Fjords National Monument. A harbor crammed with enormous cruise ships, and hundreds of tourists milling about the streets of Ketchikan. An insane 4th of July fireworks battle—featuring armored boats firing flamethrowers—at the normally laid back logging town of Thorne Bay. An aborted attempt to navigate the mudflats of aptly named Dry Strait on a falling tide. Andy’s and Bob CJ’s adventures during their 1,300-mile trip from Kenmore, Wash. to Petersburg, Alaska were too numerous to count. But we took some pictures:

A contrast in traveling styles—Osprey cruising Ketchikan (Bob CJ)

Chart watching is a constant activity while underway (Bob CJ)

Kayaking the shores of Walker Cove, Kenai Fjords National Monument (Bob CJ)

Chanced upon this sow brown bear and cub while kayaking magical Misty Fjords (Bob CJ)

Watching him graze on the lush shoreline grass, we nicknamed this male brown bear “Blondie” (Andy Ryan)

This massive rock face at Punchbowl Cove, Misty Fjords, is reminiscent of Yosemite—if one could boat through Yosemite! (Bob CJ)

BW of the entrance to Walker Cove, near Behm Strait. (Bob CJ)

Is the sky trying to tell us something about tomorrow’s weather? (Andy Ryan)

Supper aboard Osprey at Thorne Bay (Bob CJ)

Bob CJ navigating Wrangell Narrows, en route to Petersburg

Bob CJ navigating Wrangell Narrows, en route to Petersburg

Norwegian Rosemaling in Petersburg (Mary Susan Ryan)

Dinner at Inga’s Galley seafood restaurant in Petersburg with our friends Sally, Sue and Rocky

Bob and Andy at the end of their epic 1,300-mile journey (Mary Susan Ryan)

Postcard from Ketchikan

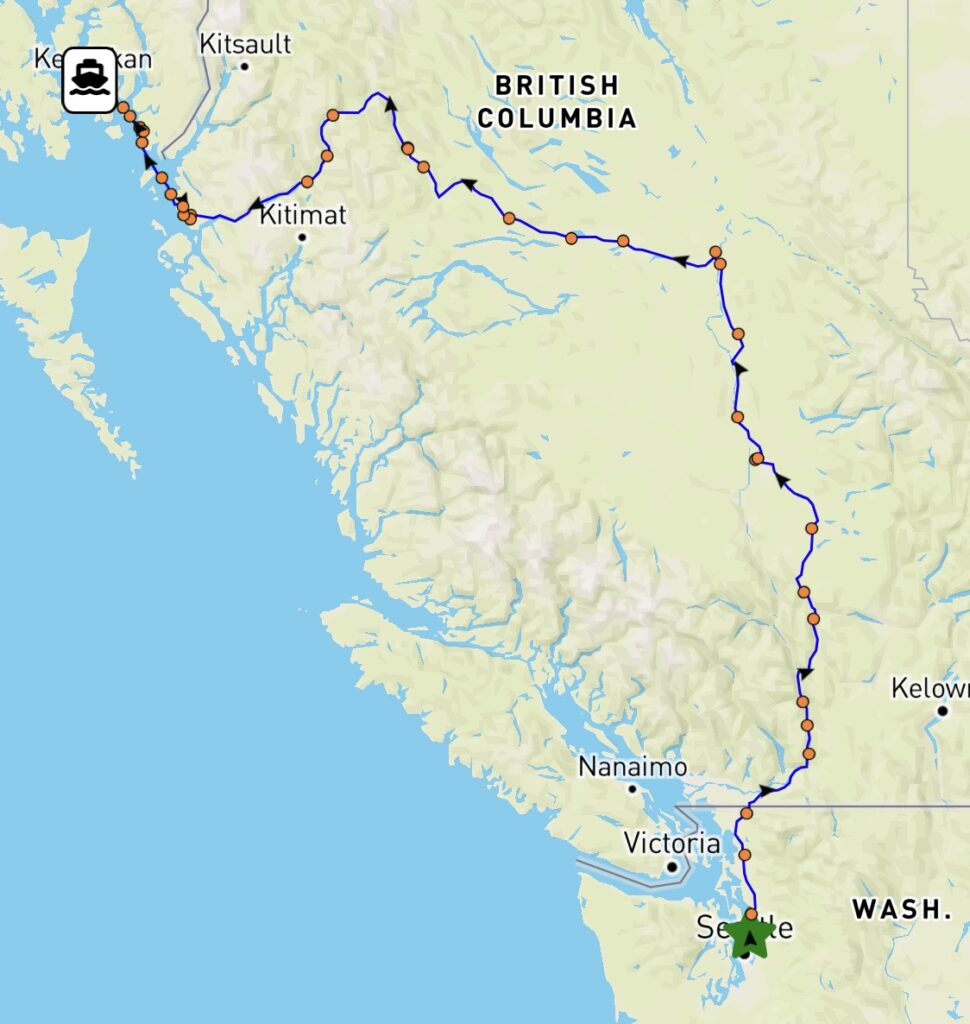

POSTCARD FROM KETCHIKAN. Day six of our voyage, and we’re getting underway again—with 1,100 land and sea miles already under our belts. Our trip has taken us hundreds of miles along British Columbia’s mighty Fraser and Skeena rivers, with Osprey in tow behind my stalwart Ford Explorer to our launching point at Port Edward, B.C. From there it was another 100 nautical miles to Ketchikan, where we have been chilling for the past two days.

Kenmore to Ketchikan

(Bob CJ)

Carving by Nathan Jackson at Cape Fox Lodge, Ketchikan (Bob CJ)

View from anchorage at Foggy Bay, Alaska (Bob CJ)

Bar Harbor Marina, Ketchikan (Bob CJ)

Go/no go decision at Port McNeill

Red indicates areas with gale warnings

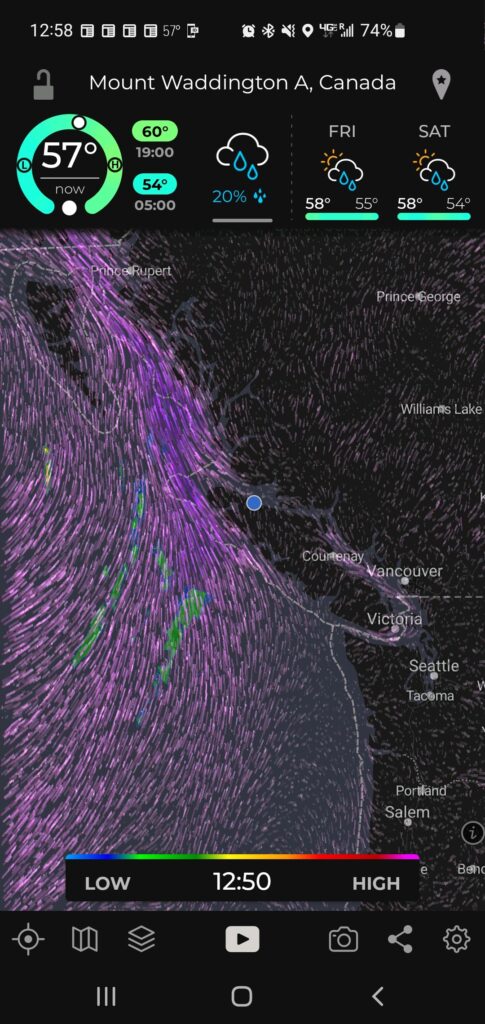

UNSEASONABLY BAD WEATHER off Vancouver Island’s Cape Scott, and from the tip of the island down the northwest coast, has been the norm for the past two weeks. For a few hours Friday it looked as though there might be a two-day weather window that would allow Osprey to make a 112-mile dash around the cape to the nearest port, Winter Harbour. I got up at 4 a.m. Saturday, started the engines … and then read the updated weather report:

The Marine Weather Forecast In Detail:

Environment Canada Forecast Issued: 400 AM PST

GALE WARNING IN EFFECT

Winds…Wind Northwest 10 To 20 Knots Except Northwest 20 To 30 South Of The Brooks Peninsula. Wind Becoming Westerly 15 Early This Morning Then Increasing To Northwest 15 To 25 Sunday Morning Except Northwest 20 To 30 South Of The Brooks Peninsula Sunday Morning And Afternoon And Northwest 30 To 35 South Of The Brooks Peninsula Tuesday Late In The Day.

Waves … Seas 1 To 2 Metres Building To 2 To 3 Sunday Evening.

Monday … Winds Northwest 20 To 30 Knots Becoming Northwest 25 To 35 Late In The Day.

Tuesday … Winds Northwest 20 To 30 Knots Becoming Northwest 25 To 35 Late In The Day.

Wednesday … Winds Northwest 20 To 30 Knots Becoming Northwest 25 To 35 Late In The Day.

In plain U.S. English that means sustained winds as high as 40 miles per hour, with wave heights up to 10 feet.

My friend Harvey sent me a picture of what the wind was doing along my planned route. He wrote, “Andy. Here’s the weather. Icky.”

Gale force southwest winds off Vancouver Island coast. Blue dot shows Osprey’s location

So, aaack! As a Kipling character lamented, in The Elephant’s Child, “This is too buch for be!” No need to intentionally sail into a perfect storm, and I was running out of time to wait it out.

I turned Osprey around and headed south, back down the island’s east coast— where the weather was surprisingly calm. Running with radar in a little fog at the north end of often-scary Johnstone Strait, but clearer as I went further south at close to wide open throttle, 25 miles per hour, now suddenly very eager to get home. All the way down Johnstone Strait and through turbulent Seymour Narrows, with the current running at 9 mph against me. No problem for my agile little boat. Refueling at Campbell River, past Comox and Nanaimo, to a pretty cove south of Dent Rapids, where I anchored in 10 feet of water, after a 203-mile Osprey-record-shattering run. Whew! Madness.

Yesterday, Sunday, an easy 70 more miles back to our starting point, Cap Sante Marina, after a wireless check-in with U.S. Customs, using the handy CBP Roam app. The marina assigned me to Slip 66.

As you can see, slip 65 was taken. A few minutes later, one of the seals gave birth—on the dock! She growled at anyone who came close to her new baby.

That concludes this 889-mile adventure. Shorter than I had hoped for, but tremendously rewarding, and certainly safer than what the weather gods had planned for me if I’d tried to go around the west side of the island.

Health, scheduling, and finances permitting, I’ll give it another try, next year.

As a famous pig said, frequently, “Th-Th-The, Th-Th-The, Th-Th … That’s all, folks!”

Afloat in the misty isles

White sand beach in Burdwood Group, Broughton Islands (Julie Burman)

JULIE AND I MOTORED INTO northeast Vancouver Island’s Port McNeill after a two-week, 673-mile maritime road trip that took us from the densely populated Puget Sound region to the glorious reaches of British Columbia’s remote Desolation Sound and Broughton Archipelago. It was rejuvenating to get out of Megalopolis, if only for a while. I believe Ms. Burman (the best of sports) and I remain pals—a remarkable accomplishment for two people shoe-horned for 15 days into a boat cabin the size of a tiny jail cell, much of the time in drizzle and fog.

Here’s a selection of Julie’s photos from a most memorable voyage:

Basking on the bow (Julie Burman)

Asiatic lilies, Lund

Entering Desolation Sound (Julie Burman)

Toba Inlet, Desolation Sound (Julie Burman)

Coast Range glaciers, from Toba Inlet (Julie Burman)

Lacy Falls, in Tribune Channel, Broughton Archipeligo (Julie Burman)

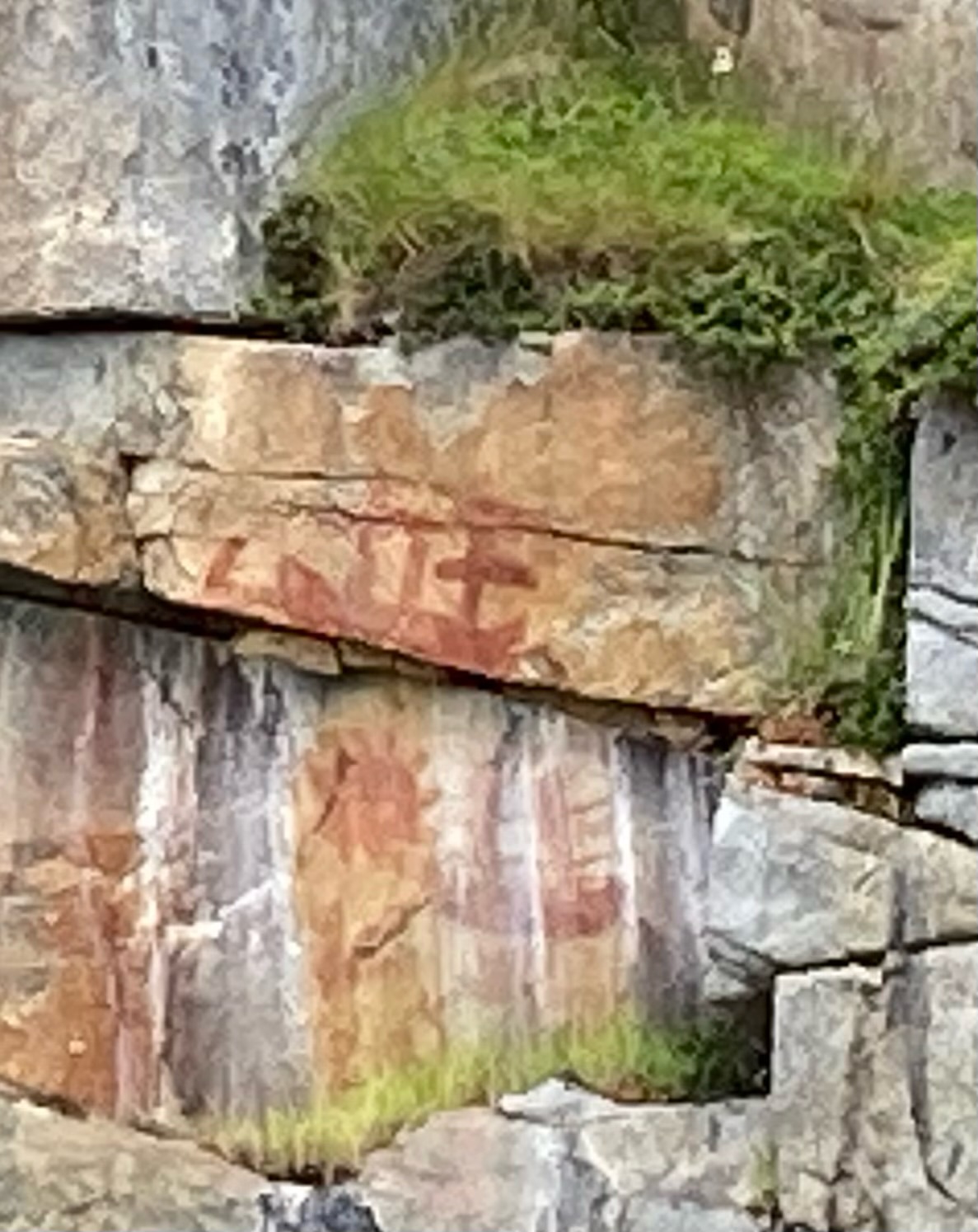

Pictograph of sailing ships, near historic First Nations village of Karlukwees, along Beware Passage (Julie Burman)

Paddle board campers on the edge of Queen Charlotte Strait (Julie Burman)

Entrance to the historic village of Mimkwamlis (Village Island), which was occupied until 1972 by the Mama̱liliḵa̱la First Nation. (Julie Burman)

Ruins on Village Island (Julie Burman)

Village Island (Julie Burman)

At Village Island (Julie Burman)

‘Namgis original burial grounds and totems, Alert Bay (Julie Burman)

Giant halibut-man carved by Stephen Bruce, 1995, Alert Bay (Julie Burman)

Alert Bay net shed (Julie Burman)

Buster Islet, among the Fog Islets, Broughton Archipelago (Julie Burman)

Julie Burman, at Sullivan Bay Marina

We’re off!

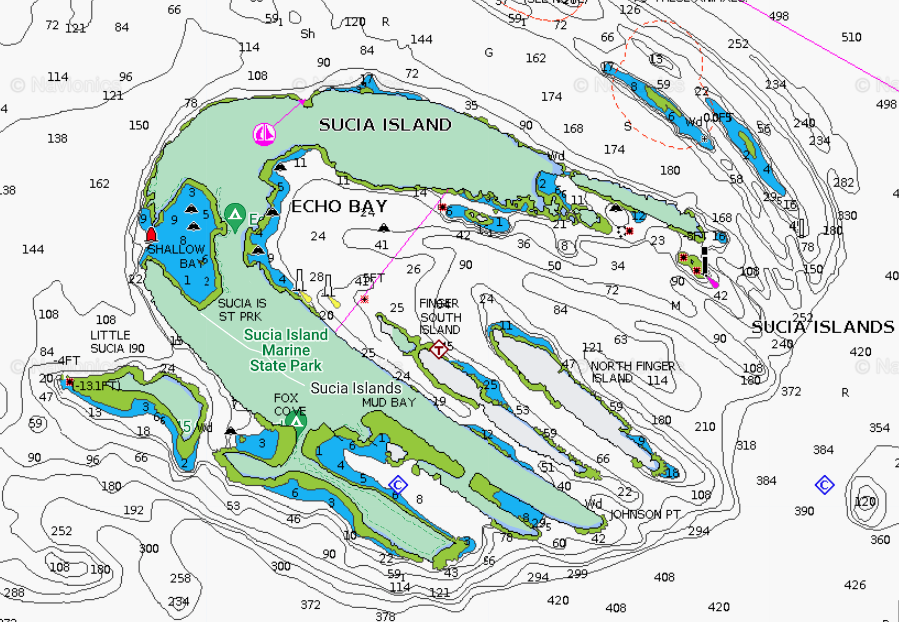

MINUTES AGO OSPREY WAS LAUNCHED, uneventfully, at Cap Sante Marina’s travel lift. Today, Julie and I will head for lovely Sucia Island, once a hotbed of smuggling activity, where we’ll do some kayaking and hiking. Then, first thing tomorrow morning we’ll motor eight miles across Boundary Pass, and cross the border (at about latitude 48.735276, longitude -123.121060). Canadian Customs is another seven miles to the west, Bedwell Harbour, on Pender Island.

You can follow our progress on Twitter, and (if I’ve got our satellite beacon set up correctly, not a certain thing), see our location on a map which is updated every 10 minutes. And if you click on this link, it should take you to a map that will allow you to send us satellite messages. Cool, huh?

Most likely, I won’t be posting a lot of stories while the trip is in progress. WI-FI connections are spotty on the east side of Vancouver Island, and almost non-existent on the west side. So, photos and stories won’t be available here until I get back, in mid-August.

* * *

In the days leading up to our departure, Julie practiced assembling and disassembling her new origami-like Oru kayak. It was not an intuitive operation, and required a trip to REI to get the procedure dialed in. Fortunately, Julie’s dog, Buster, was available to supervise.

Practice disassembly of Oru (Elena Ruano Diez)

Folding the Oru (Elena Ruano Diez)

More folding (Elena Ruano Diez)

… and reassembled, ready for trip (Elena Ruano Diez)

Shakedown cruise

THERE ARE MORE THAN 200 ITEMS remaining on my checklist and I’m crossing them off one by one: replace the old flares, check the CO2 in the self-inflating life vests, pack PB Blaster solvent, U.S. and Canadian flags, spare anchor, clothes pins, Moleskin, fillet knife, wind gauge, and wing nuts. Re-splice the anchor rode. Bring washers, fuses, Rescue Tape, clam shovel, cameras, sponges, insect repellent, freeze-dried food … and do a shakedown cruise with Julie Burman, who will be my trip partner from Anacortes, Wash. to Port Hardy, B.C.

Julie and I had to get our systems dialed in before setting off on a 400-mile, two-week voyage up the east coast of Vancouver Island (with side trips through Desolation Sound and the Broughton Archipeligo), in a boat with a cabin not much larger than a V.W. camper. It’s a tight space, and I have been known to be impatient with lubberly crew members. Not saying that’s a regular occurrence, but there is potential for crossed wires and strained friendships.

Osprey at the dock, kayaks loaded, Cap Sante Marina (Julie Burman)

So, in mid-May we loaded kayaks on Osprey’s roof, and set off on a three-day, 103-mile jaunt through the San Juan Islands, with two nights at anchor in Sucia Island State Park’s Shallow Bay.

There were so many things for us to work on, so little time. Julie needed to get familiar with the C-Dory—starting the engines, safety procedures, location of life vests. Plotting a course, steering and adjusting the boat’s trim, emergency communications with other vessels and the Coast Guard via VHF radio and satellite locator beacons. Checking anchoring depths with sonar. Anchoring with at least 4:1 scope (the ratio of deployed anchor line and chain to the depth of the water). Folding the dinette table down into a berth. Stowing supplies, cooking on the Wallas diesel stove. I needed to practice the tricky mechanics of launching and retrieving our kayaks on Osprey’s roof.

Julie at the helm

Setting out from Cap Sante Marina, in Anacortes, we charted a course south through the Swinomish Waterway, out into Skagit Bay and through Canoe Pass. Julie had the conn. We crossed busy Rosario Strait to Lopez Pass, between Decatur and Lopez Islands, and wound our way north and west through narrow Pole Pass, between Orcas and Crane Islands. And then up President Channel on the east side of Orcas, and across Boundary Pass to Sucia Island.

Sucia Island

Shallow Bay has at least eight mooring buoys but we wanted the calmest part of the bay to practice our maneuvers. Fortunately, Osprey’s is very shallow draft—she draws under a foot with the engines raised—and we were able to get in close to the southeast shore and anchor in about five feet of water. Great spot to practice launching and retrieving the kayaks, and for Julie to get the feel of her new 12-foot folding, origami-like Oru.

Shallow Bay

Julie in her new 12-foot Oru Bay folding Kayak, Shallow Bay

After landing her Oru on the south shore of Shallow Bay, Julie went for a short hike, iPhone camera in hand. First stop flowers. Of course.

Indian paintbrush. Also yellow and white camas, honeysuckle, calypso orchids, chocolate lilies, and mock orange near Sucia’s trails. (Julie Burman)

Sandstone (Julie Burman)

Shallow Bay shoreline (Julie Burman)

Osprey at anchor in Shallow Bay, Andy paddling toward her in Eddyline Equinox kayak (Julie Burman)

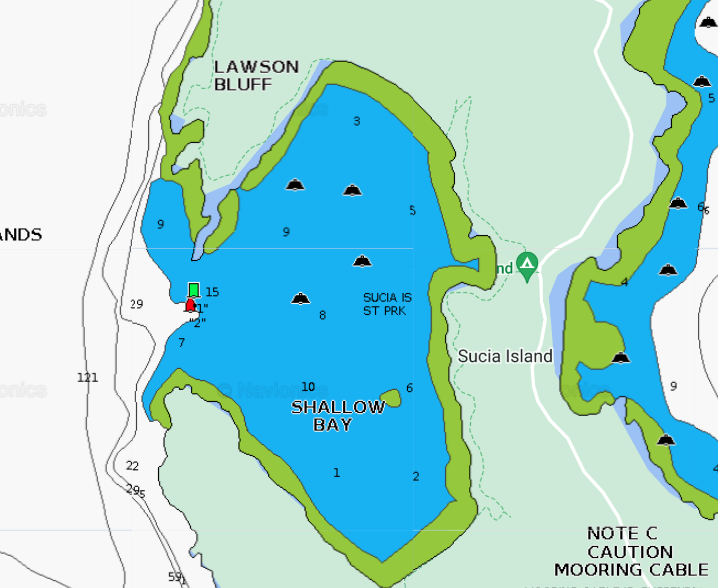

Meanwhile, at the same time we were concentrating on all these little details essential to sea-going harmony, back on Vashon Island Julie’s family—husband Bob, Spanish exchange student Elena, and resident canine Buster—were forlorn. Buster bravely tried to fill the gaping void Julie had left behind her.

“Okay people, here is your grocery list. Don’t forget the bags.” (Elena Ruano Diez and Bob Sargent)

“Yoga and stretches make my day much better and calmer. I love having quiet mornings.” (Elena Ruano Diez and Bob Sargent)

“A weeded bed is a sight to behold. Nice day to care for my plants.” (Elena Ruano Diez and Bob Sargent)

“Do you think Wo Fat will be captured in this episode?” (Elena Ruano Diez and Bob Sargent)

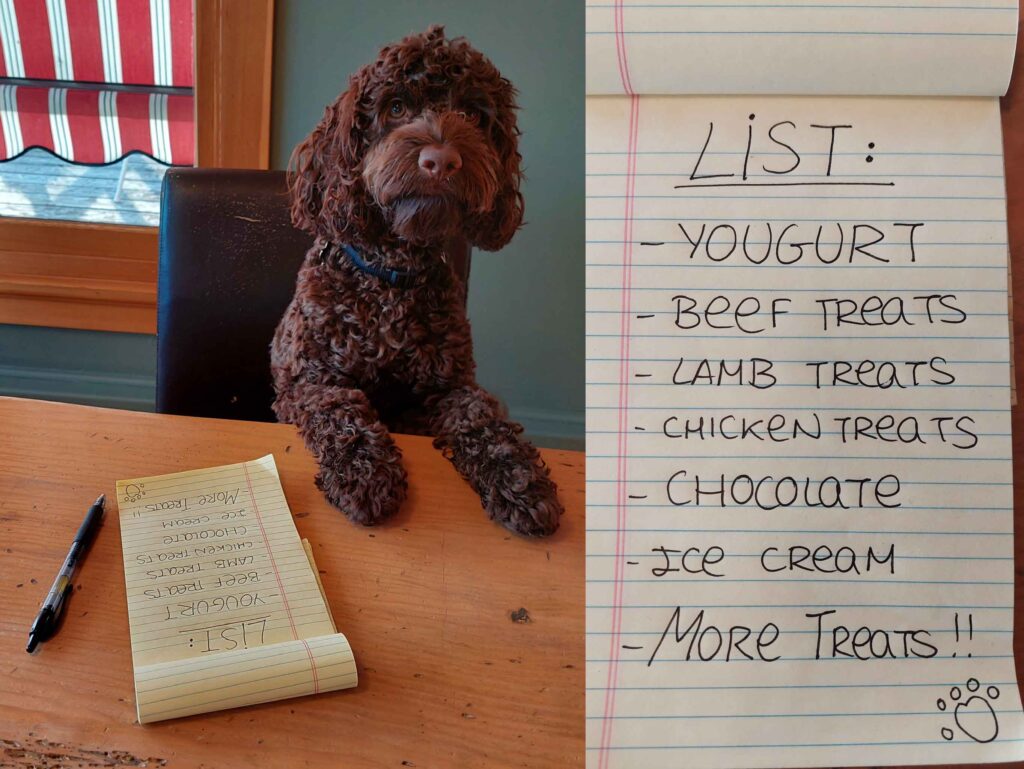

Vancouver Island circumnavigation

Osprey’s proposed route around Vancouver Island, July–August 2022. Click map for details (Google Maps)

TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY YEARS ago, 38-year-old Spanish explorer Dionisio Alcalá Galiano and his crew became the first white people to demonstrate that what we now know as Vancouver Island is in fact … an island. In the spring and summer of 1792, the Spanish mariners proved this point by sailing around the enormous body of land, counterclockwise, from Nootka Sound on the island’s west coast.

Dionisio Alcalá Galiano (Wikipedia)

Indigenous peoples, who had lived on the great island for thousands of years, were likely unimpressed by this “discovery.” But still—navigating through miles of twisting waterways, contrary winds and powerful, reversing tidal currents in 46-foot sailing ships with no motors or maps—it was a remarkable feat of seamanship. Along the way, the Spaniards had an unplanned but amicable meeting with British explorer George Vancouver, who was also circling—in the opposite direction—the island that eventually bore his name.

This summer, Osprey, a 22-foot C-Dory with twin 50-horsepower outboards, fog-piercing radar, and electronic navigation systems out the wazoo, will attempt a 950-mile circumnavigation of the world’s 43rd largest island, in the same counterclockwise direction taken by Galiano. For the first third of the voyage—from Anacortes, Wash. to Port Hardy, B.C.—skipper Andy Ryan will be joined by his longtime friend Julie Burman. After that, he’ll be on his own.

Starting June 30, you can follow our progress and message us—on Twitter; and on a web map updated by satellite every 10 minutes.

Galiano, incidentally, lived for 12 more years after his circumnavigation of Canada’s big western island. By October 18, 1805, the now 50-year-old master mariner had risen to the rank of commodore, and was in command of a 76-gun ship of the line—part of a combined French-Spanish armada in the service of Napoleon Bonaparte. Off Cape Trafalgar, on the southwest coast of Spain, the French and Spanish encountered a smaller British fleet commanded by Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson. In the ensuing battle, Galiano was killed by a cannon ball. The British fleet famously won that contest; but Lord Nelson—later lionized as hero of the engagement—also perished, shot down on deck by a French sniper.

A portrait from the late 18th century by an unknown artist, believed to depict George Vancouver (Wikipedia)

Galiano’s twin 46-foot schooners Mexicana (left) and Sutil during the 1792 voyage around Vancouver Island. Mount Baker is in the background. (José Cardero, 18th Century Spanish artist)