Posts by andy

North of Cape Caution

Great Bear Rainforest, British Columbia

AFTER A YEAR-AND-A-HALF COVID-19 CLOSURE, the northern border has finally opened—for U.S. citizens heading to Canada. (The southbound border restriction for Canadians remains in place until at least Sept. 24.) In early September my brother Bill and I will set out in little Osprey on a three-week exploration of the Great Bear Rainforest, the last sizeable area of coastal rainforest on earth.

Stretching more than 250 miles, from north of Vancouver Island to the Alaska border, the 24,711-square-mile wilderness is larger than 10 individual U.S. states*, or about the size of Ireland. Environmentalists, who may have (for the moment at least) succeeded in protecting 85 percent of the area from logging, often tout it as “the Amazon of the North.”

Osprey in Jervis Inlet, B.C.

I have traveled through this wild country once before, in 2019, on my way south in Osprey from Alaska. It is a place beautiful beyond my powers of description, home to a number of culturally thriving First Nations communities. The Great Bear Rainforest is also home to eagles, wolves, grizzly bears, salmon, sea lions, cougars, orca, seals, humpback whales, and sea otters (to name just a few species)—and local Native villages (Klemtu in particular) appear to be benefitting from the region’s increased prominence as an eco-tourism destination.

If Bill and I are really lucky, we’ll catch a glimpse of the rare white “spirit bear,” a subspecies of American black bear found only here, and a charismatic travel industry poster child.

Spirit bear Ursus americanus kermodei (Wikipedia)

Here’s a link to a trailer for a film about the rainforest, which is showing in IMAX theaters around the world.

For most of our trip we’ll be out of cellphone range, so we won’t be able to make regular updates to this page. Photos and stories will have to wait until our return. If our inReach satellite communicator works properly, we should be able to post short, frequent Tweets to this page, as well as show our current position, which can be viewed here.

*West Virginia, 24,087 square miles; Maryland, 9,775; Vermont, 9,249; New Hampshire, 8,969; Massachusetts, 7,838; New Jersey, 7,419; Hawaii, 6,423; Connecticut, 4,845; Delaware, 1,955; and Rhode Island, 1,034.

A selection of Harvey’s photos

HERE IS A SMALL COLLECTION OF MARVELOUS PHOTOS not included in my other posts, which Harvey took while SleepyC and Osprey traveled together in the Broughton Archipelago and along the Inside Passage during the summer of 2019. (All captions by Harvey)

See red, violet and blue—Always looking for some red in the sunset, foretelling a good day in the morning. Mound Island Sunset (Harvey Hochstetter)

Morning not missed—Early morning, the fog dissipates and there are a few hours of quiet time before the typical winds come on the big straits. Discovery Passage (Harvey Hochstetter)

Morning mercury magic—Early morning, bright fog breaking makes silver on SleepyC’s boat wake (Harvey Hochstetter)

Steps to wonder—Thinning overhead fog allows the sun brightness to highlight the soft steps of the hard wake of Osprey. Near Bonwick Island (Harvey Hochstetter)

On point—Breaking through the fog onto flat water in Johnstone Strait, near Turn Island (Harvey Hochstetter)

Who’s looking for me—Owl carving on a boardwalk shelter at Alert Bay, along the waterfront walk. Cormorant Island (Harvey Hochstetter)

Totem and big house—Facing the community meeting place, the Big House used for special events. Alert Bay, Cormorant Island (Harvey Hochstetter)

Red, bold and proud—Modern cliff drawing by First Nations artist Marianne Nicolson, a member of the Dzawada’enuxw Tribe of the Kwakwaka’wakw First Nations (Harvey Hochstetter)

Blue on blue with a touch of red—Osprey reflections near Gilford Island (Harvey Hochstetter)

Dock or not, and away—Government dock near Shawl Bay (Harvey Hochstetter)

Editor’s note: what Harvey doesn’t mention in the above caption is that Osprey had been tied up to the dock only seconds before; that the place was swarming with no-see-ums (the bane of Andy’s existence in the north country); and that Osprey is now fleeing the horror as rapidly as possible.

On Billy Proctor’s dock, going back in time—The home of Billy Proctor, a British Columbia legend and community stalwart, is just around the corner from Echo Bay Marina, on Gilford Island (Harvey Hochstetter)

The Martin Sheen, making a statement—A sailing vessel on loan to the Sea Shepherd organization, “patrolling” the fish farms in the Broughtons, often with celebrities on board (Harvey Hochstetter)

Bound and determined in blue—Hundreds of commercial fishing vessels are not working this year but some have managed to find a use for their boats to continue to make a living (Harvey Hochstetter)

Big white on Blackney Passage, into Blackfish Sound—A cruise ship, on its way to Alaska through the Inside Passage, makes its way through an area common for both orca and humpback whales. Broughton Archipelago (Harvey Hochstetter)

Hints to infinity—As the sun warms the air, the fog on the water dissipates and yet it lingers in the bays and canyons, accentuating the overlapping planes. Broughton Archipelago (Harvey Hochstetter)

Shapes and a trail in blue—Mirror flat water reflects a contrail as the last wisps of fog hang on the edges of the islands. Broughton Archipelago (Harvey Hochstetter)

Water, rock, fog and a boat—As the fog lifts, visibility increases and allows for increase in speed, with increased safety. Johnstone Strait (Harvey Hochstetter)

Breaking Up Magic—Osprey racing toward the disappearing fog, making up for lost time. Johnstone Strait (Harvey Hochstetter)

Crossed wakes, magic on the water—Traveling together, side by side, the wakes make a cross or “X.” It is relevant to the expression, “crossing wakes” used as a reference to meeting again and traveling together. Broughton Archipelago (Harvey Hochstetter)

Morning, oh for many more—The beauty of the early morning sunrise hides, barely visible in the silhouette, the ugliness of an open net pen fish farm. Berry Cove, Gilford Island. Broughton Archipelago (Harvey Hochstetter)

Almost home

Sunset at Tribune Bay

THIS IS THE LAST NIGHT OF MY TRIP. Tomorrow, my friend Jonathan will join me at Seattle’s Shilshole Marina and help me get through the Ballard Locks into freshwater Lake Washington and on to Kenmore—home—at the north end of the lake.

After I’m settled in and have the boat and my gear cleaned up and stored for the winter, I’ll write a summary post; and when he gets home, Harvey will send me some of his favorite pictures from the trip, which I’ll post here.

But, barring last-minute excitement transiting Lake Washington tomorrow, my trip is over. I have been out since May 31, 97 days, and have logged 3,674 nautical miles, or 4,228 land miles.

That’s a little more than the distance by land from Seattle to Managua, Nicaragua, or by sea from New York to London.

In the past four days, in my eagerness to get home, horse galloping for the barn, I’ve traveled about 230 nautical miles, from Campbell River, B.C. to Kingston Wash. One of those days—when I decided I can get across the border TODAY if I push it—was 110 nautical miles.

Last night out: Port of Kingston Marina, Kingston, Wash.

Osprey at the dock, Kingston

So I’ve been eager to get home; but it’s been a wonderful adventure. I had good luck, with the boat, my health and the weather, and I feel very fortunate to have made the trip. After I get this posted (iffy wifi at the Port of Kingston Marina), I’ll walk up the street for supper at the pub, and then turn in early for my last night afloat.

Since leaving Campbell River, I have been treated to some wonderful sights, including a gorgeous sunset at Tribune Bay, on Hornby Island, my last night in Canada. Thanks, Canadians, for being such kind, generous people. The weeks I spent in your waters were exhilarating. I hope to be back.

The last few days have been filled with … many lighthouses, including:

Chrome Island Lighthouse, off southern tip of Denman Island, B.C.

Point Wilson Light, near Port Townsend, Wash.

Point No Point Light, at the entrance to Puget Sound (almost home now)

Tuesday, I made my last “big water” crossing, about 18 nautical miles across the East Entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. It’s always a good idea to treat the Strait with respect—especially at the East Entrance, which gets the full brunt of wind funneled uninterrupted down the Strait for 80 miles from the Pacific. There can be fierce winds and high seas here, but fortunately the weather was calm Tuesday.

The Strait is also known for fog, however, and as I turned the corner south, from Anacortes, down Rosario Strait and into Juan de Fuca, I hit a wall of fog and visibility dropped to a few hundred feet.

Thick fog in Strait of San Juan de Fuca

After long white-knuckle minutes, eyes glued to the radar screen, I emerged from the fog at the entrance to Admiralty Inlet—and what looked like a flotilla of vessels heading straight at me. Yipes, one of the ships appeared to be … a Trident nuclear submarine.

A red 25-foot Coast Guard Response Boat, with an M60 machine gun mounted on the bow separated itself from the the other vessels and came roaring up alongside Osprey. Hailing me on channel 16, the coasties told me they were escorting the sub out from the Trident base at Bangor. They asked me, very politely, to stay 1,000 yards from the sub—and then ran parallel beside me for several minutes to be sure I did.

Trident sub and escort vessels at entrance to Admiralty Inlet, Olympic Mountains in background

When the sub and its escorts had passed, I motored through the churning Point Wilson tidal rip, across to Port Townsend, which is getting ready for the big annual Wooden Boat Festival, this weekend. I’m back in home waters now; back in the place I love best.

Work area at Northwest Maritime Center

Norwegian faering, under construction at the Maritime Center

Sea smoke

Osprey entering Johnstone Strait fog bank (Harvey Hochstetter)

WE GROPED THROUGH THICK, THICK FOG for 20 miles, inching our way down the infamous Johnstone Strait, with a 3-knot current against us. Most of the time, Harvey’s boat was out in front while I tried to keep him in sight—no easy task with visibility often less than two boat lengths.

Using radar and AIS—a technology which shows the position of boats equipped with a special transmitter—we were able to gauge the location, heading and speed of other vessels traveling in both directions along the 60-mile-long channel. Harvey radioed approaching boats, to discuss how we’d pass each other. “Green to green,” keeping their starboard, or right side, to ours; “red to red” to pass port to port.

“How thick is the fog where you are?” Harvey would ask the other boat.

“Maybe 200 feet, maybe less.”

“Same here, hard to see anything. Have a safe trip.”

Sea smoke (Harvey Hochstetter)

(Harvey Hochstetter)

When traveling in fog, you try to use all of your senses. You stare intently ahead, hoping something won’t suddenly materialize out of the murk, while simultaneously watching the navigation screen for radar blips and AIS markers. You sniff for the smell of nearby land. And you listen—for the thrum of approaching engines, the sound of waves breaking on a reef, the clang of bell buoys, for other boats’ fog horns.

Sleepy C and Osprey are equipped with automatic horns, which can be set to sound a warning every two minutes. I had used mine in dense fog several times on my trip, taking some comfort knowing other boats could at least hear my approach. But several days before we reached Johnstone Strait we’d tested our horns—at what distance could they really be heard?

The results were dismaying. We had hoped the horns would be very loud—audible at least a mile away. When put to the test, though, we learned they couldn’t be heard until the two boats were just a few feet apart.

***

In the two weeks before we entered Johnstone Strait, Harvey and I had been traveling around the Broughton Archipelago. My understanding of this area was greatly enhanced by a visit to the homestead of Billy Proctor, a legendary fisherman and logger-turned-environmentalist. Billy, who will be 85 this October, has been working for years to restore wild salmon runs that were destroyed by overfishing and horrible environmental practices including clear-cut logging, blanket spraying of pesticides, and the introduction of open pen-net salmon farms on an industrial scale.

Billy Proctor (Harvey Hochstetter)

In his autobiographical book (highly recommended) Heart of the Raincoast: a Life Story, co-authored by renowned naturalist Alexandra Morton, Proctor talked about the destruction he has seen over the years:

In 1957, the BC Forest Service did an aerial spray of the north end of Vancouver Island. They sprayed from Blinkhorn Peninsula in Johnstone Strait to Cape Scott, Nigei Island and Hope Island. They sprayed with DDT and they did it in May, just when all the fry and smolts were leaving the rivers. The reason they sprayed was to kill a bug that was killing spruce trees. I was in Goletas Channel on my way home from Bull Harbour when they were spraying Nigei Island. They used two big four-engine planes and they had a thousand gallons of DDT in each plane.

There were holes along each wing and as they went there was a fog behind them. This went on for a week or more. There were stories of people with wheelbarrows full of dead tiny fry from the banks of the Nimpkish River. After that, there were no big runs of coho or springs to the Nimpkish River.

… Traditional fishing grounds were barren and who was to blame? Loggers were damming streams, preventing salmon from going upriver, and clear-cut logging was killing eggs on the spawning beds. Salmon eggs incubating in gravel need a constant flow of water to survive, and when a hillside is clear-cut, the soil washes downhill with each rainfall, clogging the little spaces between the pebbles and smothering the eggs.

Clear-cutting also warms river water, which is deadly to the cool-loving salmon. Pesticides were flowing into the creeks, poisoning juvenile fish. Relentless, increasing fishing pressure meant fewer and fewer salmon were returning to these damaged rivers, further decreasing survival. No one knew what was happening to the fish once they were out to sea. Warm currents, lack of food and increased predation kill salmon where we never see it.

What is amazing, and infuriating, to me is that these ruinous, backward, and unsustainable—stupid—practices continue to this day, aided and abetted by the B.C. and Canadian governments. In the Broughtons we passed through channels which for majesty would rival Alaska’s famed Misty Fiords National Monument—were it not for mountains vandalized by fresh clearcuts, mile after mile, with large Atlantic salmon farms seemingly around every bend.

Here’s some of what we saw (all uncredited photos on this website by Andy Ryan):

Broughton Archipelago clearcuts

… and open net-pen fish farms

(Harvey Hochstetter)

(Harvey Hochstetter)

(Harvey Hochstetter)

***

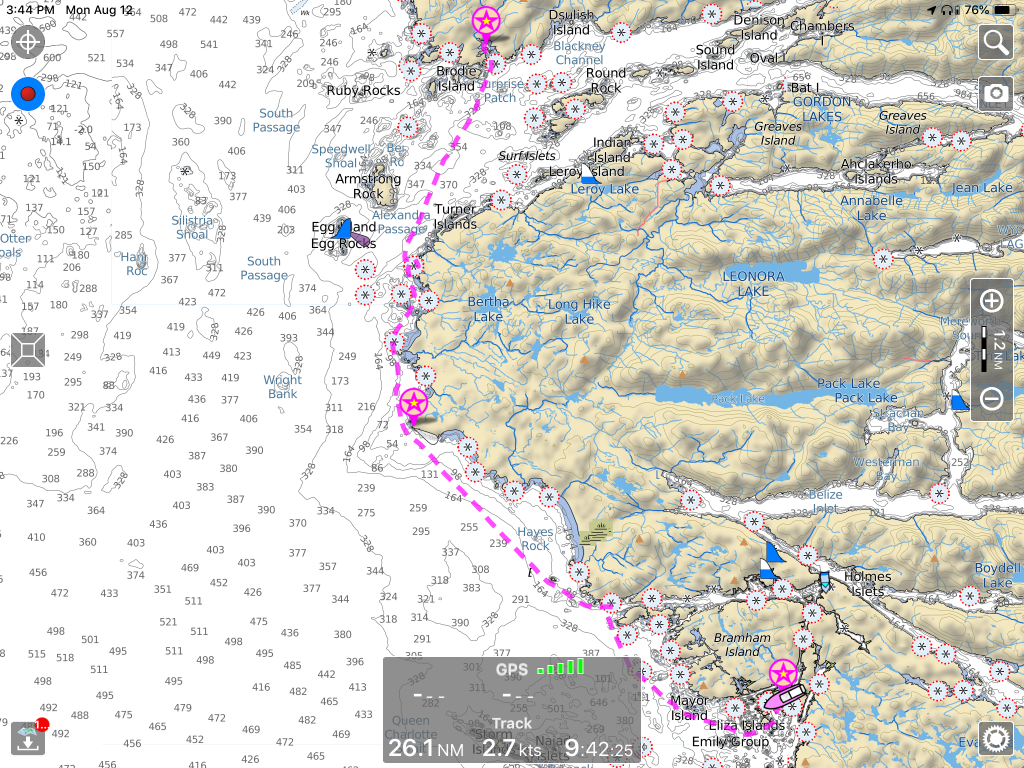

Port Harvey to Campbell River, via Johnstone Strait

After four hours the fog in Johnstone Strait began to lift, and the shoreline slowly emerged. We could see again. The current had turned, going with us, and we were able to bring our boats up on plane and speed down the channel to Seymour Narrows. We got there an hour before the peak of the 14-knot ebb and rode the tide through churning rapids down to Campbell River.

Salmon trollers, tied at the dock, Campbell River (Harvey Hochstetter)

The salmon trolling fleet in this pretty town has been tied up at the dock all summer. Not enough fish for commercial openings, and no one can say exactly why. It could be the massive landslide that closed the Fraser River to fish passage earlier this year. Some say it could be Japanese drift-net fishing once again interdicting returning salmon. Or it could be the things people like Billy Proctor and Alexandra Morton have been warning us about—fish farming, logging, mining, industrial-scale application of pesticides, fertilizer runoff, loss of habitat, culverts and dams obstructing salmon migration routes.

All of these things are within our power to change. As the old Pete Seeger song goes, “I swear it’s not too late.”

Bad news for wild fish

Osprey passing an open net-pen salmon farm in the Broughton Islands this summer (Harvey Hochstetter)

DON’T BUY FARMED SALMON—and consider boycotting stores that sell it. Ask your friends to do the same.

As I’ve made my way along the British Columbia coast this summer, I have been struck by the number of floating fish factories—open net-pens containing hundreds of thousands of genetically altered Atlantic salmon—infesting these waters.

There is no rational reason I can see for the Canadian government to allow these ugly insults to the planet, which pose a very real threat to the five species of Pacific salmon that have sustained coastal people (and orcas and bears) for thousands of years. Salmon are the very soul of the North Pacific coast.

British Columbia’s neighbors, Alaska and Washington state, have implemented outright bans on net-pen salmon farming.

Bumper sticker seen at Alert Bay

The B.C. salmon farms, over 100 of them, are located along migration routes for native fish stocks, and there is conclusive scientific evidence that fish farms provide ideal breeding conditions for parasitic sea lice. The lice attach themselves to juvenile native salmon; it takes only two or three lice to kill a young fish.

According to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, “Wild salmon close to fish farms are 73 times more likely to suffer lethal sea lice than juveniles not adjacent to fish farms. A fish farm can also elevate the rate of sea lice infestation in salmon up to 40 miles from their pens. Sea lice can survive for about 3 weeks off their host—making transfer from farmed to wild salmon possible.”

Worse than sea lice, perhaps, up to 95 percent of open net-pen Atlantic salmon in British Columbia are infected with Piscine Reovirus, a highly contagious disease which can cause heart and skeletal inflammation in salmon. The strain of the virus found in B.C. fish farms is believed to have originated in Norway, introduced to the environment along with the farmed fish.

And yet, inexplicably, the Canadian government has pressed for regulations which would specifically allow disease-infected salmon to be introduced into B.C. net pens. Opponents of net-pen farms have been met with stonewalling in their attempts to obtain correspondence between industry and government scientists.

There are signs like this in villages up and down the B.C. coast. This one’s in Alert Bay

Salmon farming is big business, and you have to wonder if someone is getting paid off.

The many First Nations people I have spoken with along the coast this summer have expressed strong opposition to open net-pen salmon farming, which they see as a direct threat to their way of life. Salmon are at the heart of native spiritual and cultural practices, and are the most important subsistence resource for people who make their livings from the sea.

As of this date, Jonathan Wilkinson, Canadian minister of fisheries and oceans (along with Canada’s Coast Guard), has been unresponsive to their concerns about the hazards of net-pen salmon farming, local people have told me.

So before you buy that salmon filet, check where it came from. If it doesn’t say wild salmon, or if it says “Atlantic salmon,” don’t even think about buying it. You’ll be doing Mother Earth a favor; and besides, farmed salmon—treated throughout their lives with pesticides and antibiotics—doesn’t taste good.

Here are some photos Harvey took as we passed yet another net-pen operation in the Broughton Islands this week:

Two Harveys

Harvey Hochstetter and Sleepy C

MY FRIEND HARVEY HAS JOINED ME in Port McNeill. Harvey is another C-Dory owner, and for the next couple of weeks we’ll be buddy-boating through the Broughton Islands archipelago, at the eastern end of Queen Charlotte Strait.

Harvey brought Sleepy C up from Sequim, Wash. two weeks ago. Since then, he has been helping the owner of the Port Harvey (no relation) Marina, Gail Cambridge, get her possessions packed up for her move back to Alberta. Gail’s husband George died suddenly, a year ago, and Gail can’t run the marina by herself.

Harvey had come to know the Cambridges over a couple of summers cruising in the Broughtons; he became a more active supporter of the little mom and pop marina last year when a local man sought to have part of the bay rezoned, to permit the operation of a noisy, ugly shipyard directly across from the marina.

The Cambridges believed the industrial operation would destroy the solitude and quiet of their beautiful little cove. And their business along with it.

Port Harvey Marina

I followed the rezoning process from afar, reading local newspaper stories online and listening to first-hand accounts from Harvey, who drove up to Port McNeil to participate in the hearings. For a number of years I worked as a newspaper reporter, covering local, state and federal government—and from what I could see, in the pro-development environment that seems to prevail up here, the deck was stacked against the Cambridges. They never had a chance.

At one point, the marina’s dock sank, for no apparent reason. Harvey is convinced it had to have been sabotage.

On May 15, 2018, despite considerable local opposition, the Regional District of Mount Waddington adopted Bylaw 895, rezoning the Cambridges’ neighbor’s land—from “rural” to “marine industrial.”

In a news release sent out after the Mount Waddington District’s decision, George Cambridge said he would appeal the ruling.

“An industrial scale marine repair and salvage business being operated at this location is incompatible with all other adjacent uses,” Cambridge wrote. He added that the regional district violated one of its own bylaws, “that no rezoning bylaw can be enacted that allows a new use that is incompatible with existing adjacent uses.”

The Cambridge family

George set up a GoFundMe page in an attempt to raise the estimated $80,000 cost of fighting the ruling … and then everything ended for the Cambridges and the Port Harvey Marina. Three months after the zoning decision, George died in his sleep of an apparent aneurism.

And so, for the past couple of weeks, Harvey and a small band of friends have been helping Gail Cambridge pack up the memories of a long, happy marriage. A water taxi was scheduled to take her away this week. Harvey and I have plans to stop off at the now vacated marina, for a last look, on our way back from the Broughtons.

Along the spirit bear coast

Great Bear Rainforest (Source: Mapbox Streets)

FROM THE TIME I CROSSED FROM ALASKA INTO CANADA, across wide Dixon Entrance, I was in the “Great Bear Rainforest.” The name, a public relations masterstroke, was coined in a San Francisco restaurant one night in the late 1990s by environmentalists working to protect one of the world’s last great temperate rainforests.

“We wanted people to hear the name and be mad as hell that anybody could turn it into toilet paper,” one of the activists wrote in a later memoir. Local residents reportedly were not consulted in the naming, but it appealed to the media and general public, and it stuck.

After a well-funded international campaign, targeting big lumber suppliers like Home Depot, the British Columbia government threw in the towel. In 2016 the prime minister declared 85 percent of the rainforest off limits to commercial logging. Depending on which website you want to believe, the protected area encompasses most coastal areas of northern B.C., and is between 12,000 and 22,000 square miles in size.

(If I’m getting any of is wrong, please let me know and I will make appropriate corrections.)

For the past two weeks, I have been slowly working my way down the outer coast of the rainforest, among dozens of archipelagos, hundreds of islands, with winding passages leading out to the ocean. Three of these outer islands are home to a rare subspecies of black bear—the Kermode or spirit bear (Ursus americanus kermodei). Ten to 20 percent of Kermode bears here—from 100 to 500 individuals—are white and I had hoped I might see a white spirit bear. But not this trip; I’ll have to come back.

This place is sacred to the indigenous people whose home it has been for thousands of years. And now it’s sacred to me.

Here’s some of what I saw along the way:

Prince Rupert docks in the fog, from Casey Cove

Kelp beds on outer coast reef

Fog rolls in on the outer coast

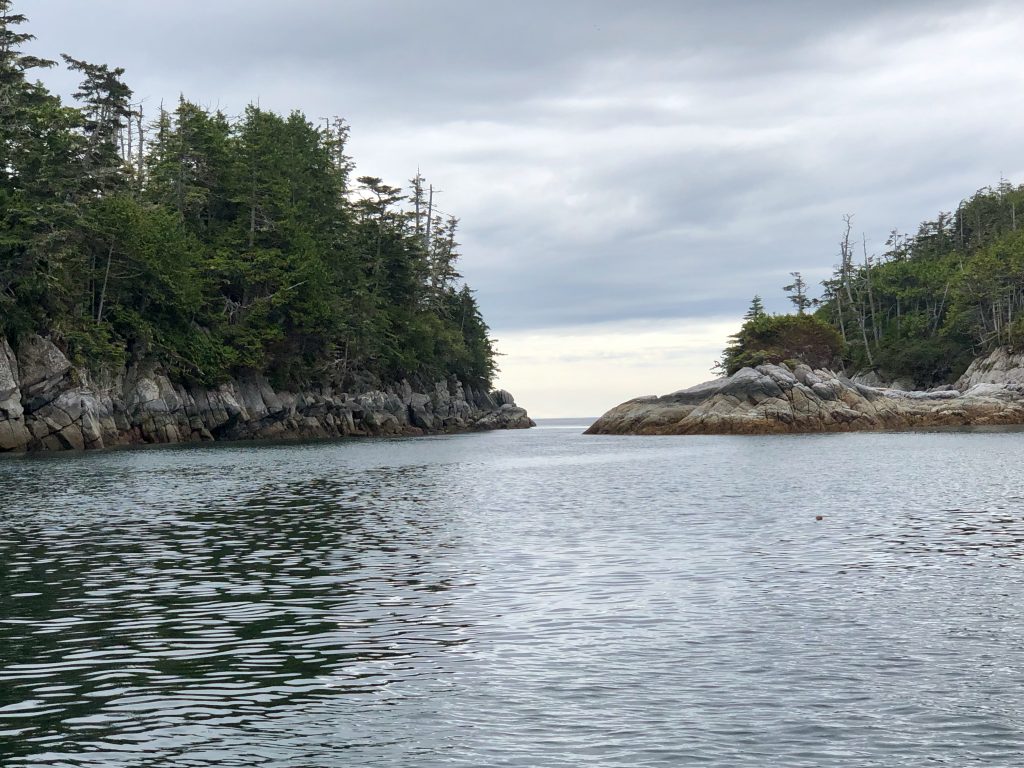

Island passages …

… around rocky points

Sometimes with the assistance of lighthouses …

Robb Point Light

Dryad Point Light, north of Bella Bella

A jellyfish nursery at Lewall Inlet (look very closely, there are several)

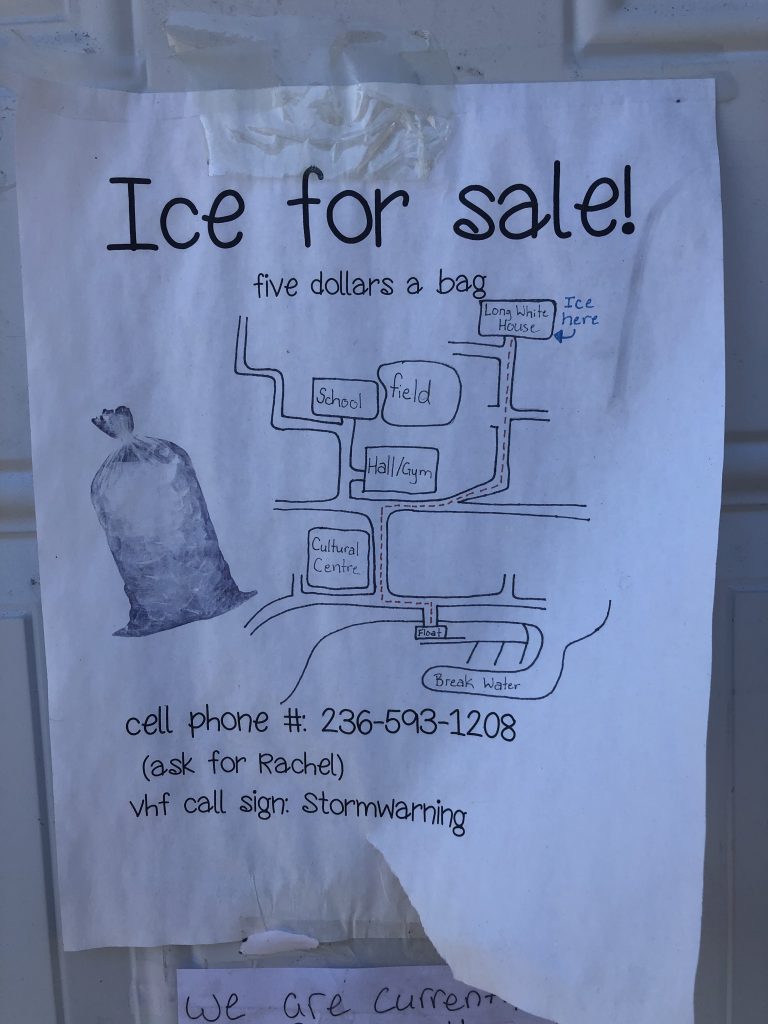

Ice for sale at Klemtu

Mt. Buxton, Calvert Island

Around Cape Caution

Cape Caution

And into Murray Labyrinth, where it was time for reflections.

Nathan and Dorica Jackson

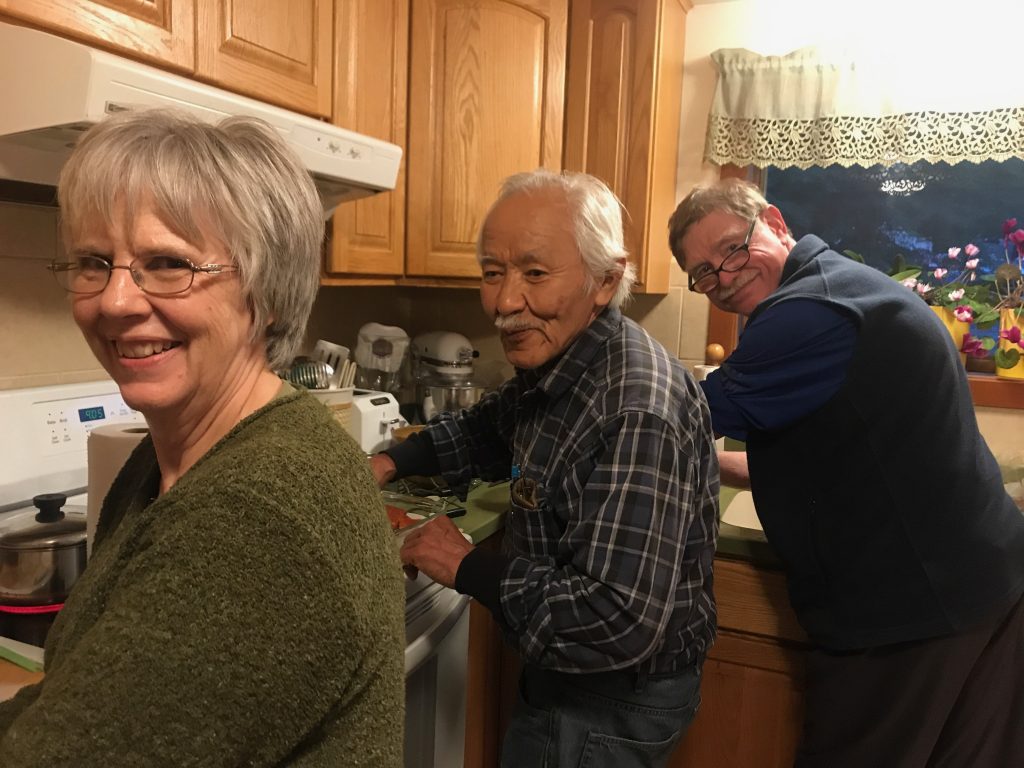

Dorica and Nathan Jackson (left) and Andy Ryan canning sockeye salmon in the Jacksons’ kitchen (Marla Williams)

MARLA AND I WERE HONORED TO HAVE DINNER, twice this week, with renowned Alaska Native artist Nathan Jackson and his wife, master weaver and textile artist Dorica Jackson. After our second dinner with the Jacksons, at their home near Ketchikan, we helped them put up a mess of sockeye salmon Nathan caught earlier in the week, purse seining.

If you’re not familiar with Nathan’s spectacular work, you can see examples of it, here.

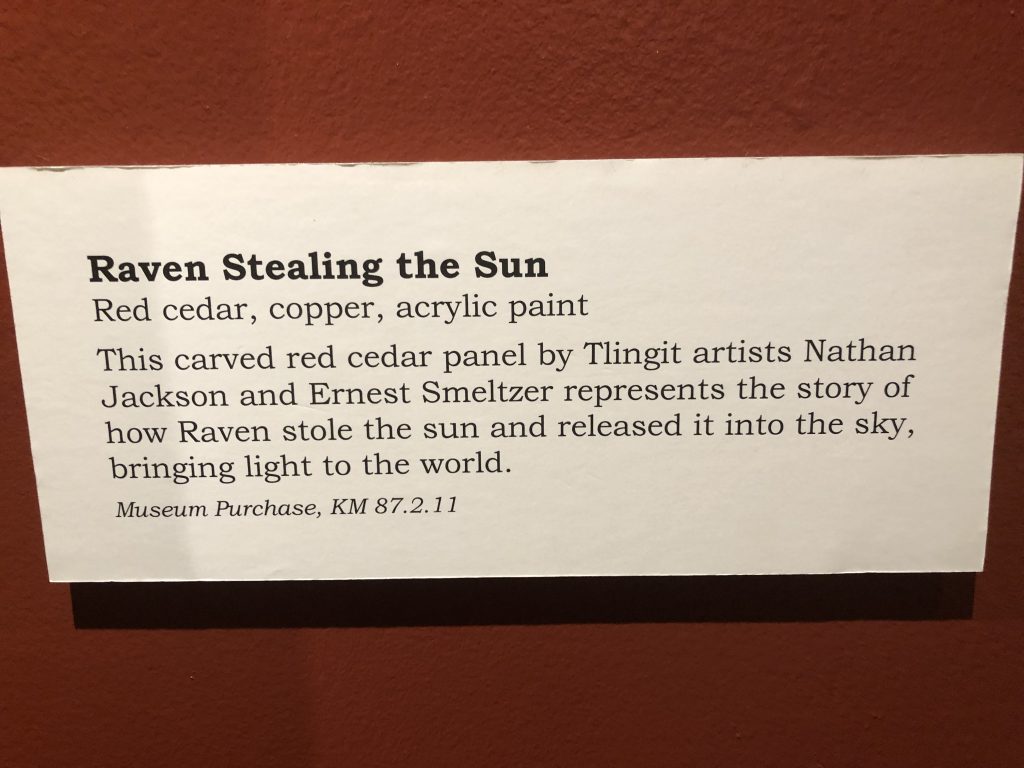

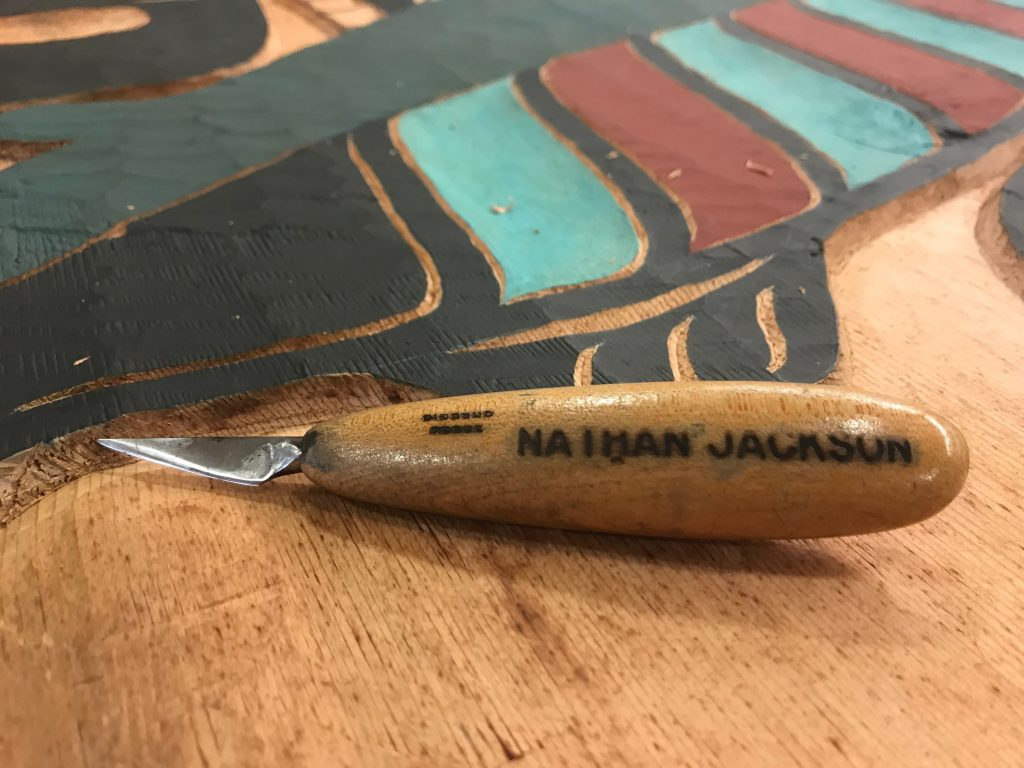

Raven Stealing the Sun, by Nathan Jackson and Ernest Smeltzer. Displayed at the Totem Heritage Center, Ketchikan

Nathan is the subject of a documentary by Marla, which begins airing this September on Alaska Public Media. The film is one in a six-part series, Magnetic North: The Alaskan Character.

Nathan Jackson airs Sept. 9, at 9:30, on Alaska Public Media. The series also includes films about:

—Clem Tillion

—Arliss Sturgulewski

—Roy Madsen

—Jacob Adams

—Bill Sheffield

The series is directed by Marla and edited by Kyle Seago. Funding provided by Rasmuson Foundation in association with the Alaska Humanities Forum.

For more information email akhf@akhf.org

Here are a few more photos from our visits with the Jacksons:

In Nathan’s workshop (Marla Williams)

Nathan, preparing sockeye for canning (Marla Williams)

Jars of salmon, ready for the pressure cooker (Marla Williams)

Dorica Jackson (Marla Williams)

Chilkat robe by Dorica, recently purchased by the Ketchikan Museums Department, with help from a Rasmuson Foundation grant. (Photo courtesy Ketchikan Museums)

Pit stop in Ketchikan

Ken Perry, Timber & Marine Supply, Ketchikan

ONE OF THE BIGGEST MISTAKES I MADE in preparing for this trip was neglecting to ask my outboard motor dealer if I would be able to get service on my way north for the new Tohatsu 50s I was considering buying.

Outboards require service every 100 hours, and I figured the trip would put at least 300 hours on the engines. I foolishly assumed that, because I had told the dealer I was buying the motors for a trip to Alaska, I would be able to get them serviced along the way.

Oops. It wasn’t until after I’d purchase the Tohatsus that I started trying to line up service appointments for the trip. I learned there are no Tohatsu dealers north of Nanaimo, on lower Vancouver Island.

Fortunately I was able to talk Ken Perry, owner of Timber & Marine Supply, into servicing the engines when I arrived in Ketchikan. But he gave me unceasing (but good-natured) grief about it every time I saw him. Ken asked for my dealer’s email address—for the purpose, I thought, of inquiring about Tohatsu parts.

Not exactly. Here’s what Ken wrote to my dealer:

“FYI for your future customers, why did you sell your customer (Andy Ryan) a pair of Tohatsu motors for his C Dory, knowing that he was going to travel through the inside passage of Alaska? There isn’t a single Tohatsu service center or dealer in any of Southeast Alaska. I also understand that you are a Honda Marine Dealer.

“There are multiple Honda Marine dealers in Canada and multiple Honda Marine dealers in S E Alaska. You can get a Honda outboard serviced in almost any town and no one will touch a Tohatsu Outboard. I’m just trying to save your future customers from heart ache and disapointment.

“Thank You Ken”

Ken’s shop did great work on my engines on my way north, and I stopped at his shop again on my way back south. After subjecting me to some mild ridicule, he serviced the engines—and said the Tohatsus and I would be welcomed back if I ever venture north again.

But Ken’s larger point is well taken: if the Tohatsus break down between here and Nanaimo, I may need a long, long tow home.

Wind

Windy day in Clarence Strait, seen from Meyers Chuck

DAVE POINTED TO THE DARK MASS OF CLOUDS over Anan Lagoon to the south and said in classic meteorological understatement, “It’s going to rain in about an hour.”

I hadn’t been been paying attention to the weather. Osprey was snugged into a little cove in front of the Anan Bay cabin, tied to a Forest Service float. Very protected. Dave was starting dinner. A floating Forest Service rangers’ cabin was anchored to our south, further out into the bay.

Then the wind hit—more suddenly than anything I’ve experienced, transforming the cove in seconds from a flat calm duck pond to a churning, frothing washing machine.

The float was bucking like a terrified horse, and Dave bravely climbed out of our boat and onto the pitching platform to tie down our kayaks, which were about to blow away. Then he quickly climbed back into Osprey. And we just watched.

Cove at Anan Bay on a calm day, with float and floating Forest Service rangers’ cabin (USFS photo)

It was remarkable: although there were only a few feet of fetch—the distance over which wind blows without obstruction to generate waves—a white line of two-footers marched across the narrow cove, slamming into the float. It happened too fast for us to be afraid; we were awestruck.

For less than a minute the wind seemed to slacken … and then the rain came, in sheets, sideways, obscuring everything around us. I bet it dumped two inches in less than three minutes. And then, as quickly as the storm had blown in, it was calm again.

But something was different, and it took a little while for us to realize what it was. The float to which we were tied was closer to shore; and the floating rangers’ cabin, which had been well to the west of us before the storm hit, was now less than 100 feet away.

Forest Service rangers’ cabin close to Osprey’s bow after dragging anchor during wind storm

We called the floating cabin on our VHF radio. The three Forest Service employees aboard—who now appeared to be anxiously evaluating the cabin’s new position—confirmed that all four of the cabin’s anchors had dragged. And from their vantage point, it seemed clear our float’s anchors had dragged as well. They told us they thought their anchors had finally dug in … but we all kept close watch through the night, just in case.

The next morning we made a quick trip to the Anan Bay bear observation station—no grizzlies and only a couple of black bears. There were salmon in Anan Creek, however, and the bald eagles were thick.

Our national symbol

Assemblage of eagles at Anan Lagoon

Black bear, heading for the woods

Brook running into Anan Lagoon

Then we got back on the water—and met more wind. We had intended to go from Anan Bay to Thorne Bay, with a seven-mile crossing of blustery Clarence Strait. But the weather was from the south, and forecasters were calling for 15- to 20-knot winds in the strait for the next four days.

So, rounding Lemesurier Point into Clarence Strait, we stuck close to the eastern shore, heading south into a four-foot chop, and ducked into the protected harbor of Meyers Chuck.

Meyers Chuck, refuge from the storm

The next morning, as she had on the outbound leg of Osprey’s voyage, legendary Meyers Chuck baker Cassy brought fresh, homemade cinnamon buns right down to the boat.

But there wasn’t a minute to spare. It looked like we had a very brief weather window, maybe a couple of hours, before Clarence Strait got rough again. So, munching on Cassy’s cinnamon rolls, we scooted out of Meyers Chuck and ran, 32 miles through heavy chop, down to Bar Harbor, in Ketchikan.