Uncategorized

We’re off!

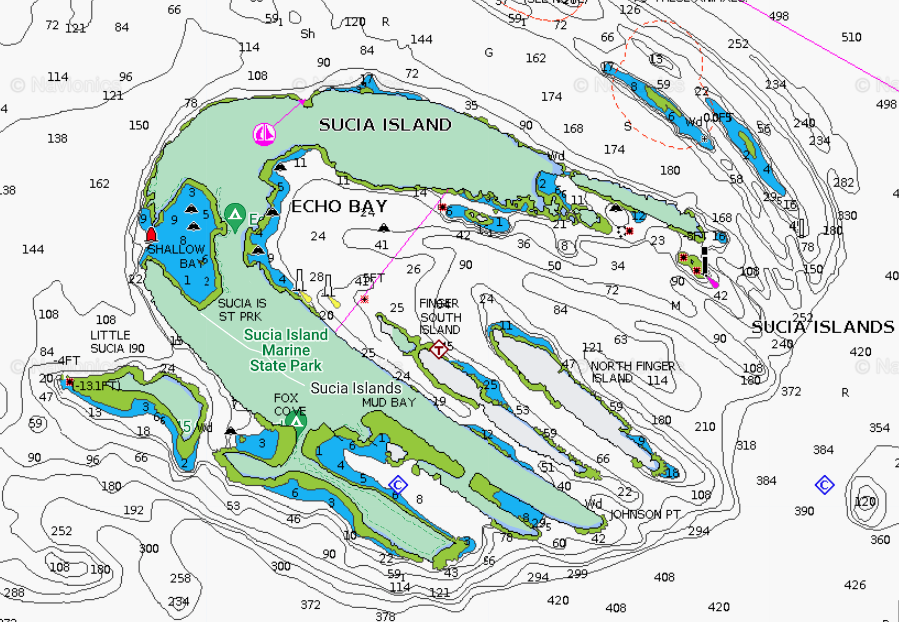

MINUTES AGO OSPREY WAS LAUNCHED, uneventfully, at Cap Sante Marina’s travel lift. Today, Julie and I will head for lovely Sucia Island, once a hotbed of smuggling activity, where we’ll do some kayaking and hiking. Then, first thing tomorrow morning we’ll motor eight miles across Boundary Pass, and cross the border (at about latitude 48.735276, longitude -123.121060). Canadian Customs is another seven miles to the west, Bedwell Harbour, on Pender Island.

You can follow our progress on Twitter, and (if I’ve got our satellite beacon set up correctly, not a certain thing), see our location on a map which is updated every 10 minutes. And if you click on this link, it should take you to a map that will allow you to send us satellite messages. Cool, huh?

Most likely, I won’t be posting a lot of stories while the trip is in progress. WI-FI connections are spotty on the east side of Vancouver Island, and almost non-existent on the west side. So, photos and stories won’t be available here until I get back, in mid-August.

* * *

In the days leading up to our departure, Julie practiced assembling and disassembling her new origami-like Oru kayak. It was not an intuitive operation, and required a trip to REI to get the procedure dialed in. Fortunately, Julie’s dog, Buster, was available to supervise.

Practice disassembly of Oru (Elena Ruano Diez)

Folding the Oru (Elena Ruano Diez)

More folding (Elena Ruano Diez)

… and reassembled, ready for trip (Elena Ruano Diez)

Shakedown cruise

THERE ARE MORE THAN 200 ITEMS remaining on my checklist and I’m crossing them off one by one: replace the old flares, check the CO2 in the self-inflating life vests, pack PB Blaster solvent, U.S. and Canadian flags, spare anchor, clothes pins, Moleskin, fillet knife, wind gauge, and wing nuts. Re-splice the anchor rode. Bring washers, fuses, Rescue Tape, clam shovel, cameras, sponges, insect repellent, freeze-dried food … and do a shakedown cruise with Julie Burman, who will be my trip partner from Anacortes, Wash. to Port Hardy, B.C.

Julie and I had to get our systems dialed in before setting off on a 400-mile, two-week voyage up the east coast of Vancouver Island (with side trips through Desolation Sound and the Broughton Archipeligo), in a boat with a cabin not much larger than a V.W. camper. It’s a tight space, and I have been known to be impatient with lubberly crew members. Not saying that’s a regular occurrence, but there is potential for crossed wires and strained friendships.

Osprey at the dock, kayaks loaded, Cap Sante Marina (Julie Burman)

So, in mid-May we loaded kayaks on Osprey’s roof, and set off on a three-day, 103-mile jaunt through the San Juan Islands, with two nights at anchor in Sucia Island State Park’s Shallow Bay.

There were so many things for us to work on, so little time. Julie needed to get familiar with the C-Dory—starting the engines, safety procedures, location of life vests. Plotting a course, steering and adjusting the boat’s trim, emergency communications with other vessels and the Coast Guard via VHF radio and satellite locator beacons. Checking anchoring depths with sonar. Anchoring with at least 4:1 scope (the ratio of deployed anchor line and chain to the depth of the water). Folding the dinette table down into a berth. Stowing supplies, cooking on the Wallas diesel stove. I needed to practice the tricky mechanics of launching and retrieving our kayaks on Osprey’s roof.

Julie at the helm

Setting out from Cap Sante Marina, in Anacortes, we charted a course south through the Swinomish Waterway, out into Skagit Bay and through Canoe Pass. Julie had the conn. We crossed busy Rosario Strait to Lopez Pass, between Decatur and Lopez Islands, and wound our way north and west through narrow Pole Pass, between Orcas and Crane Islands. And then up President Channel on the east side of Orcas, and across Boundary Pass to Sucia Island.

Sucia Island

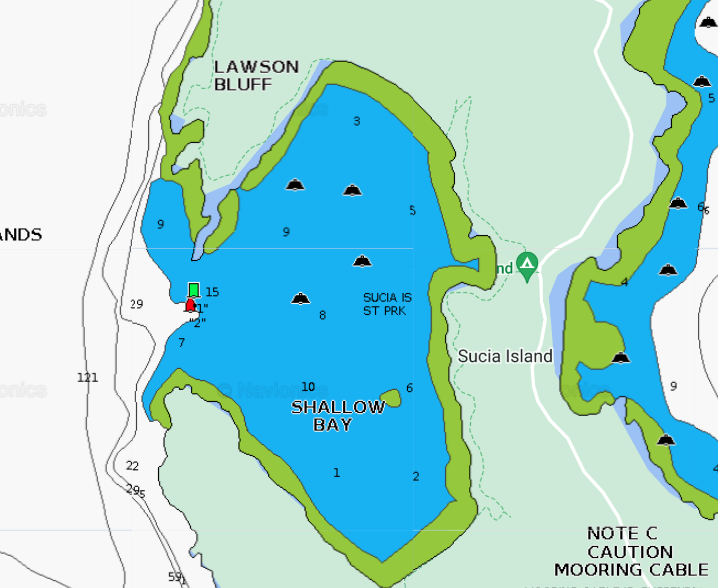

Shallow Bay has at least eight mooring buoys but we wanted the calmest part of the bay to practice our maneuvers. Fortunately, Osprey’s is very shallow draft—she draws under a foot with the engines raised—and we were able to get in close to the southeast shore and anchor in about five feet of water. Great spot to practice launching and retrieving the kayaks, and for Julie to get the feel of her new 12-foot folding, origami-like Oru.

Shallow Bay

Julie in her new 12-foot Oru Bay folding Kayak, Shallow Bay

After landing her Oru on the south shore of Shallow Bay, Julie went for a short hike, iPhone camera in hand. First stop flowers. Of course.

Indian paintbrush. Also yellow and white camas, honeysuckle, calypso orchids, chocolate lilies, and mock orange near Sucia’s trails. (Julie Burman)

Sandstone (Julie Burman)

Shallow Bay shoreline (Julie Burman)

Osprey at anchor in Shallow Bay, Andy paddling toward her in Eddyline Equinox kayak (Julie Burman)

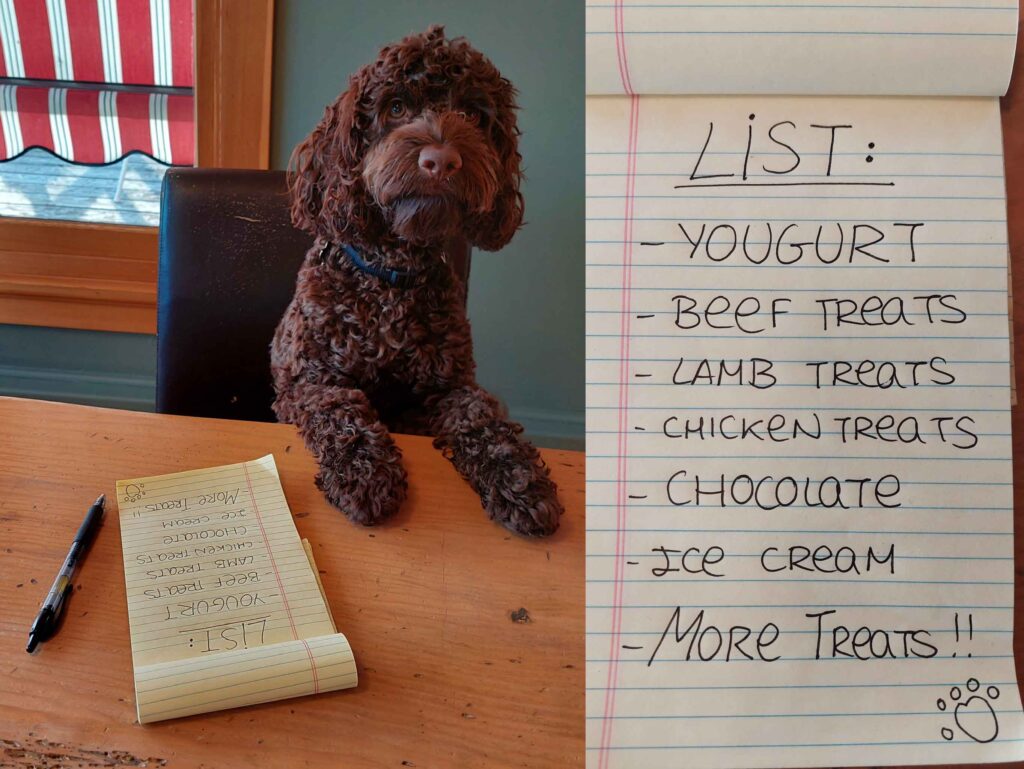

Meanwhile, at the same time we were concentrating on all these little details essential to sea-going harmony, back on Vashon Island Julie’s family—husband Bob, Spanish exchange student Elena, and resident canine Buster—were forlorn. Buster bravely tried to fill the gaping void Julie had left behind her.

“Okay people, here is your grocery list. Don’t forget the bags.” (Elena Ruano Diez and Bob Sargent)

“Yoga and stretches make my day much better and calmer. I love having quiet mornings.” (Elena Ruano Diez and Bob Sargent)

“A weeded bed is a sight to behold. Nice day to care for my plants.” (Elena Ruano Diez and Bob Sargent)

“Do you think Wo Fat will be captured in this episode?” (Elena Ruano Diez and Bob Sargent)

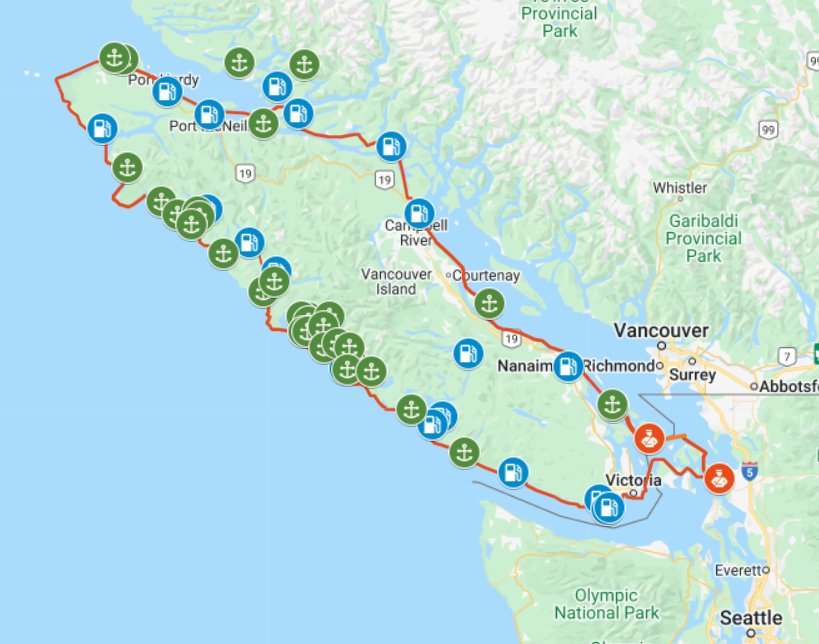

Vancouver Island circumnavigation

Osprey’s proposed route around Vancouver Island, July–August 2022. Click map for details (Google Maps)

TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY YEARS ago, 38-year-old Spanish explorer Dionisio Alcalá Galiano and his crew became the first white people to demonstrate that what we now know as Vancouver Island is in fact … an island. In the spring and summer of 1792, the Spanish mariners proved this point by sailing around the enormous body of land, counterclockwise, from Nootka Sound on the island’s west coast.

Dionisio Alcalá Galiano (Wikipedia)

Indigenous peoples, who had lived on the great island for thousands of years, were likely unimpressed by this “discovery.” But still—navigating through miles of twisting waterways, contrary winds and powerful, reversing tidal currents in 46-foot sailing ships with no motors or maps—it was a remarkable feat of seamanship. Along the way, the Spaniards had an unplanned but amicable meeting with British explorer George Vancouver, who was also circling—in the opposite direction—the island that eventually bore his name.

This summer, Osprey, a 22-foot C-Dory with twin 50-horsepower outboards, fog-piercing radar, and electronic navigation systems out the wazoo, will attempt a 950-mile circumnavigation of the world’s 43rd largest island, in the same counterclockwise direction taken by Galiano. For the first third of the voyage—from Anacortes, Wash. to Port Hardy, B.C.—skipper Andy Ryan will be joined by his longtime friend Julie Burman. After that, he’ll be on his own.

Starting June 30, you can follow our progress and message us—on Twitter; and on a web map updated by satellite every 10 minutes.

Galiano, incidentally, lived for 12 more years after his circumnavigation of Canada’s big western island. By October 18, 1805, the now 50-year-old master mariner had risen to the rank of commodore, and was in command of a 76-gun ship of the line—part of a combined French-Spanish armada in the service of Napoleon Bonaparte. Off Cape Trafalgar, on the southwest coast of Spain, the French and Spanish encountered a smaller British fleet commanded by Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson. In the ensuing battle, Galiano was killed by a cannon ball. The British fleet famously won that contest; but Lord Nelson—later lionized as hero of the engagement—also perished, shot down on deck by a French sniper.

A portrait from the late 18th century by an unknown artist, believed to depict George Vancouver (Wikipedia)

Galiano’s twin 46-foot schooners Mexicana (left) and Sutil during the 1792 voyage around Vancouver Island. Mount Baker is in the background. (José Cardero, 18th Century Spanish artist)

In the Great Bear Rainforest

Along the north coast (Bill Ryan)

Cruising British Columbia’s divine coastal waters in a compact motorboat last month, two boomer siblings had a splendid wilderness adventure.

Andy Ryan, from Kenmore, Wash., planned the excursion and captained the Osprey, a sturdy, 22-foot C-Dory. Brother Bill Ryan, a New Yorker, took photos and helped navigate.

Canada opened to Covid-vaccinated foreigners in August, creating a small window for travel to the Great Bear Rainforest before harsh weather set in. A lifelong boater, Andy had taken Osprey in 2019 up the Inside Passage from Washington to Alaska’s Glacier Bay and back, and was keen to revisit the renowned nature preserve. Novice Bill had crewed on an Alaska leg of the earlier voyage and eagerly agreed to come along.

BY BILL RYAN

On Sept. 7, we trailered Osprey across the border, onto a ferry to Vancouver Island and up to Port Hardy before launching into Queen Charlotte Strait. Our first challenge was rounding unprotected Cape Caution, where wind- and current-driven waves mix with Pacific swell in a tricky chop. Stay alert, peer through thick boat-length-visibility fog and watch for floating logs!

Over the next three weeks, we made our way north through picturesque passages between forested islands to Prince Rupert, near Alaska, and back again. At night we anchored in sheltered inlets recommended by prior mariners using the Active Captain app. Mountains with stunning waterfalls ringed some of the anchorages.

Andy (left) and Bill Ryan

Trusty Explorer pulled loaded Osprey and kayaks from Everett, Wash. to Port Hardy, BC, and back. (Bill Ryan)

Waiting for the tide before launching at Port Hardy. (Bill Ryan)

(Bill Ryan)

(Bill Ryan)

(Bill Ryan)

Along the way we spotted more than a dozen humpback whales, their blows visible from far across the water. Some traveled in processions. A few appeared close by; one broached near our starboard side.

A procession of whales (Bill Ryan)

Near Klemtu, tragically, we noticed a mass of seaweed in motion. Approaching, we saw a humpback whale, apparently trying to free itself from a tangle of fishing net and kelp. We circled helplessly as it floundered; there was nothing we could do and we motored north in search of help.

A few miles further up the east coast of Swindle Island, we spotted a Kitasoo/Xai’xais Guardian Watchmen boat. Pulling alongside, we reported the trapped marine mammal and its location. The young Watchmen seemed to believe there was a good chance of saving the whale, and sped off to the rescue. Andy has attempted to find out what became of the hapless cetacean, but thus far has not been able to connect with the Guardian Watchmen. He will keep trying. Bill shot video of the whale, and it is awful to watch. But we don’t see any good reason to sanitize our account. The video is posted here.

Whale tangled in rope and kelp (from video).

Coastal Guardian Watchmen, First Nations environmental protectors (Bill Ryan)

We only ventured ashore a few times in the Great Bear Rainforest, and always at places with docks. The shores were rocky and slippery, and there weren’t many good places to land. The pristine area, now mostly protected from logging, is home to white “spirit bears,” a subspecies of the American black bear, revered by local native people. We did not see any, but did sight one of their black bear cousins on a beach as we motored by.

During a normal summer, these waterways would be thick with pleasure boats and cruise ships. But this year, post-season, we rarely saw another boat—an occasional tug pulling an enormous barge or a big BC Ferries ship. We had days of wooded solitude between far-apart fuel stops.

Bill at the helm (Andy Ryan)

Sighting a black bear (Ursus Americanus) on the north shoreline of Hunter Island (Bill Ryan)

B.C. ferry in the distance (Bill Ryan)

Getting a little too close for comfort (Bill Ryan)

Sadly, due to Covid, Klemtu, Bella Bella and other First Nations communities on our route were closed to visitors. But we spent several days at the welcoming Shearwater Resort, newly aquired and managed by the Heitsuk Nation, while we waited for a strong gale to pass.

With Klemtu closed and our gas running low, it looked as though our trip might be cut short; fortunately, the fuel dock at the village of Hartley Bay—a two-day trip, 66 nautical miles north of Klemtu—was open for business. With our gas tanks now full, we headed up gorgeous Grenville Channel—waterfalls on each side for 45 miles—and on to Prince Rupert, the farthest north city on the B.C, coast.

We were now just 24 miles from the Alaska border … but Prince Rupert was the end of the line for us. Summer was but a memory on the north coast. The wet, windy season had set in, with one low pressure system rolling in after another, and we decided not to risk a crossing of notoriously rough Dixon Entrance, with Ketchikan just a few more hours to the north. Instead, we hunkered down in driving rain for a couple of days, rocking gently in a slip at the Prince Rupert Rowing and Yacht Club. (Hot showers and a laundromat! Sweet!) Then we headed back south.

We had planned on gassing up again at Hartley Bay, but—oops!—the fuel dock was closed that day. We reduced our speed to save gas (Osprey doesn’t have tremendous range) and crept south. After two nervous days we made it back to Shearwater … on fumes … just in time for another powerful storm that kept us pinned to the dock for two days.

On our way south from Shearwater, we made a stop at the Hakai Institute on Calvert Island, where scientists study the ocean’s DNA and carbon levels. From there, we stretched our legs and walked to a gorgeous beach.

Bill at Hakai beach (Andy Ryan)

View from Hakai Beach (Andy Ryan)

Rock formation at Hakai Institute beach (Andy Ryan)

English garden at Hakai Institute (Andy Ryan)

OK, let’s wrap this tale up in one paragraph.

Another big weather system was closing in, and we took advantage of a momentary calm and dashed back across Queen Charlotte Sound at 20 knots to Port Hardy, pulled Osprey out of the water and began the long drive home.

And then there was that surreal late night incident at a decrepit motel in Nanaimo, where a scary tweaker threatened us, convincingly, with a homemade sword he’d had hidden under his coat. But that’s another story.

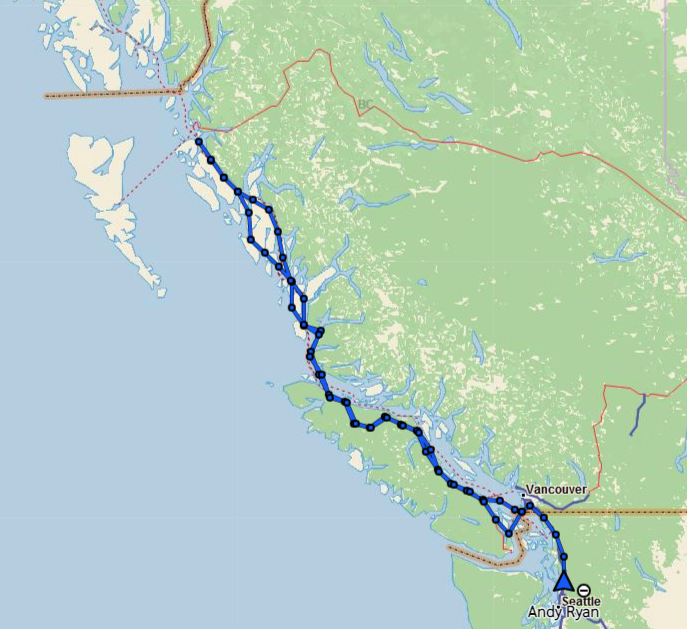

Vancouver Island and the Great Bear Rainforest (Navionics)

Track of the Osprey, September 2021 (captured by Garmin inReach device)

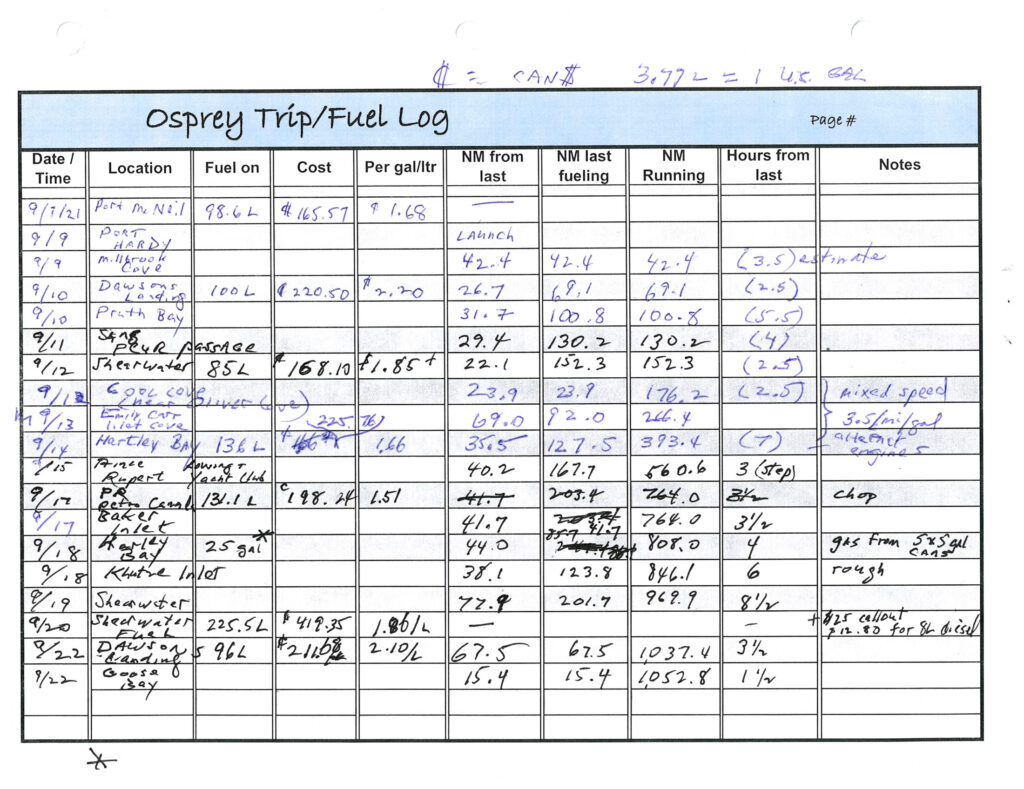

Log of the Osprey

North of Cape Caution

Great Bear Rainforest, British Columbia

AFTER A YEAR-AND-A-HALF COVID-19 CLOSURE, the northern border has finally opened—for U.S. citizens heading to Canada. (The southbound border restriction for Canadians remains in place until at least Sept. 24.) In early September my brother Bill and I will set out in little Osprey on a three-week exploration of the Great Bear Rainforest, the last sizeable area of coastal rainforest on earth.

Stretching more than 250 miles, from north of Vancouver Island to the Alaska border, the 24,711-square-mile wilderness is larger than 10 individual U.S. states*, or about the size of Ireland. Environmentalists, who may have (for the moment at least) succeeded in protecting 85 percent of the area from logging, often tout it as “the Amazon of the North.”

Osprey in Jervis Inlet, B.C.

I have traveled through this wild country once before, in 2019, on my way south in Osprey from Alaska. It is a place beautiful beyond my powers of description, home to a number of culturally thriving First Nations communities. The Great Bear Rainforest is also home to eagles, wolves, grizzly bears, salmon, sea lions, cougars, orca, seals, humpback whales, and sea otters (to name just a few species)—and local Native villages (Klemtu in particular) appear to be benefitting from the region’s increased prominence as an eco-tourism destination.

If Bill and I are really lucky, we’ll catch a glimpse of the rare white “spirit bear,” a subspecies of American black bear found only here, and a charismatic travel industry poster child.

Spirit bear Ursus americanus kermodei (Wikipedia)

Here’s a link to a trailer for a film about the rainforest, which is showing in IMAX theaters around the world.

For most of our trip we’ll be out of cellphone range, so we won’t be able to make regular updates to this page. Photos and stories will have to wait until our return. If our inReach satellite communicator works properly, we should be able to post short, frequent Tweets to this page, as well as show our current position, which can be viewed here.

*West Virginia, 24,087 square miles; Maryland, 9,775; Vermont, 9,249; New Hampshire, 8,969; Massachusetts, 7,838; New Jersey, 7,419; Hawaii, 6,423; Connecticut, 4,845; Delaware, 1,955; and Rhode Island, 1,034.

A selection of Harvey’s photos

HERE IS A SMALL COLLECTION OF MARVELOUS PHOTOS not included in my other posts, which Harvey took while SleepyC and Osprey traveled together in the Broughton Archipelago and along the Inside Passage during the summer of 2019. (All captions by Harvey)

See red, violet and blue—Always looking for some red in the sunset, foretelling a good day in the morning. Mound Island Sunset (Harvey Hochstetter)

Morning not missed—Early morning, the fog dissipates and there are a few hours of quiet time before the typical winds come on the big straits. Discovery Passage (Harvey Hochstetter)

Morning mercury magic—Early morning, bright fog breaking makes silver on SleepyC’s boat wake (Harvey Hochstetter)

Steps to wonder—Thinning overhead fog allows the sun brightness to highlight the soft steps of the hard wake of Osprey. Near Bonwick Island (Harvey Hochstetter)

On point—Breaking through the fog onto flat water in Johnstone Strait, near Turn Island (Harvey Hochstetter)

Who’s looking for me—Owl carving on a boardwalk shelter at Alert Bay, along the waterfront walk. Cormorant Island (Harvey Hochstetter)

Totem and big house—Facing the community meeting place, the Big House used for special events. Alert Bay, Cormorant Island (Harvey Hochstetter)

Red, bold and proud—Modern cliff drawing by First Nations artist Marianne Nicolson, a member of the Dzawada’enuxw Tribe of the Kwakwaka’wakw First Nations (Harvey Hochstetter)

Blue on blue with a touch of red—Osprey reflections near Gilford Island (Harvey Hochstetter)

Dock or not, and away—Government dock near Shawl Bay (Harvey Hochstetter)

Editor’s note: what Harvey doesn’t mention in the above caption is that Osprey had been tied up to the dock only seconds before; that the place was swarming with no-see-ums (the bane of Andy’s existence in the north country); and that Osprey is now fleeing the horror as rapidly as possible.

On Billy Proctor’s dock, going back in time—The home of Billy Proctor, a British Columbia legend and community stalwart, is just around the corner from Echo Bay Marina, on Gilford Island (Harvey Hochstetter)

The Martin Sheen, making a statement—A sailing vessel on loan to the Sea Shepherd organization, “patrolling” the fish farms in the Broughtons, often with celebrities on board (Harvey Hochstetter)

Bound and determined in blue—Hundreds of commercial fishing vessels are not working this year but some have managed to find a use for their boats to continue to make a living (Harvey Hochstetter)

Big white on Blackney Passage, into Blackfish Sound—A cruise ship, on its way to Alaska through the Inside Passage, makes its way through an area common for both orca and humpback whales. Broughton Archipelago (Harvey Hochstetter)

Hints to infinity—As the sun warms the air, the fog on the water dissipates and yet it lingers in the bays and canyons, accentuating the overlapping planes. Broughton Archipelago (Harvey Hochstetter)

Shapes and a trail in blue—Mirror flat water reflects a contrail as the last wisps of fog hang on the edges of the islands. Broughton Archipelago (Harvey Hochstetter)

Water, rock, fog and a boat—As the fog lifts, visibility increases and allows for increase in speed, with increased safety. Johnstone Strait (Harvey Hochstetter)

Breaking Up Magic—Osprey racing toward the disappearing fog, making up for lost time. Johnstone Strait (Harvey Hochstetter)

Crossed wakes, magic on the water—Traveling together, side by side, the wakes make a cross or “X.” It is relevant to the expression, “crossing wakes” used as a reference to meeting again and traveling together. Broughton Archipelago (Harvey Hochstetter)

Morning, oh for many more—The beauty of the early morning sunrise hides, barely visible in the silhouette, the ugliness of an open net pen fish farm. Berry Cove, Gilford Island. Broughton Archipelago (Harvey Hochstetter)

Almost home

Sunset at Tribune Bay

THIS IS THE LAST NIGHT OF MY TRIP. Tomorrow, my friend Jonathan will join me at Seattle’s Shilshole Marina and help me get through the Ballard Locks into freshwater Lake Washington and on to Kenmore—home—at the north end of the lake.

After I’m settled in and have the boat and my gear cleaned up and stored for the winter, I’ll write a summary post; and when he gets home, Harvey will send me some of his favorite pictures from the trip, which I’ll post here.

But, barring last-minute excitement transiting Lake Washington tomorrow, my trip is over. I have been out since May 31, 97 days, and have logged 3,674 nautical miles, or 4,228 land miles.

That’s a little more than the distance by land from Seattle to Managua, Nicaragua, or by sea from New York to London.

In the past four days, in my eagerness to get home, horse galloping for the barn, I’ve traveled about 230 nautical miles, from Campbell River, B.C. to Kingston Wash. One of those days—when I decided I can get across the border TODAY if I push it—was 110 nautical miles.

Last night out: Port of Kingston Marina, Kingston, Wash.

Osprey at the dock, Kingston

So I’ve been eager to get home; but it’s been a wonderful adventure. I had good luck, with the boat, my health and the weather, and I feel very fortunate to have made the trip. After I get this posted (iffy wifi at the Port of Kingston Marina), I’ll walk up the street for supper at the pub, and then turn in early for my last night afloat.

Since leaving Campbell River, I have been treated to some wonderful sights, including a gorgeous sunset at Tribune Bay, on Hornby Island, my last night in Canada. Thanks, Canadians, for being such kind, generous people. The weeks I spent in your waters were exhilarating. I hope to be back.

The last few days have been filled with … many lighthouses, including:

Chrome Island Lighthouse, off southern tip of Denman Island, B.C.

Point Wilson Light, near Port Townsend, Wash.

Point No Point Light, at the entrance to Puget Sound (almost home now)

Tuesday, I made my last “big water” crossing, about 18 nautical miles across the East Entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. It’s always a good idea to treat the Strait with respect—especially at the East Entrance, which gets the full brunt of wind funneled uninterrupted down the Strait for 80 miles from the Pacific. There can be fierce winds and high seas here, but fortunately the weather was calm Tuesday.

The Strait is also known for fog, however, and as I turned the corner south, from Anacortes, down Rosario Strait and into Juan de Fuca, I hit a wall of fog and visibility dropped to a few hundred feet.

Thick fog in Strait of San Juan de Fuca

After long white-knuckle minutes, eyes glued to the radar screen, I emerged from the fog at the entrance to Admiralty Inlet—and what looked like a flotilla of vessels heading straight at me. Yipes, one of the ships appeared to be … a Trident nuclear submarine.

A red 25-foot Coast Guard Response Boat, with an M60 machine gun mounted on the bow separated itself from the the other vessels and came roaring up alongside Osprey. Hailing me on channel 16, the coasties told me they were escorting the sub out from the Trident base at Bangor. They asked me, very politely, to stay 1,000 yards from the sub—and then ran parallel beside me for several minutes to be sure I did.

Trident sub and escort vessels at entrance to Admiralty Inlet, Olympic Mountains in background

When the sub and its escorts had passed, I motored through the churning Point Wilson tidal rip, across to Port Townsend, which is getting ready for the big annual Wooden Boat Festival, this weekend. I’m back in home waters now; back in the place I love best.

Work area at Northwest Maritime Center

Norwegian faering, under construction at the Maritime Center

Sea smoke

Osprey entering Johnstone Strait fog bank (Harvey Hochstetter)

WE GROPED THROUGH THICK, THICK FOG for 20 miles, inching our way down the infamous Johnstone Strait, with a 3-knot current against us. Most of the time, Harvey’s boat was out in front while I tried to keep him in sight—no easy task with visibility often less than two boat lengths.

Using radar and AIS—a technology which shows the position of boats equipped with a special transmitter—we were able to gauge the location, heading and speed of other vessels traveling in both directions along the 60-mile-long channel. Harvey radioed approaching boats, to discuss how we’d pass each other. “Green to green,” keeping their starboard, or right side, to ours; “red to red” to pass port to port.

“How thick is the fog where you are?” Harvey would ask the other boat.

“Maybe 200 feet, maybe less.”

“Same here, hard to see anything. Have a safe trip.”

Sea smoke (Harvey Hochstetter)

(Harvey Hochstetter)

When traveling in fog, you try to use all of your senses. You stare intently ahead, hoping something won’t suddenly materialize out of the murk, while simultaneously watching the navigation screen for radar blips and AIS markers. You sniff for the smell of nearby land. And you listen—for the thrum of approaching engines, the sound of waves breaking on a reef, the clang of bell buoys, for other boats’ fog horns.

Sleepy C and Osprey are equipped with automatic horns, which can be set to sound a warning every two minutes. I had used mine in dense fog several times on my trip, taking some comfort knowing other boats could at least hear my approach. But several days before we reached Johnstone Strait we’d tested our horns—at what distance could they really be heard?

The results were dismaying. We had hoped the horns would be very loud—audible at least a mile away. When put to the test, though, we learned they couldn’t be heard until the two boats were just a few feet apart.

***

In the two weeks before we entered Johnstone Strait, Harvey and I had been traveling around the Broughton Archipelago. My understanding of this area was greatly enhanced by a visit to the homestead of Billy Proctor, a legendary fisherman and logger-turned-environmentalist. Billy, who will be 85 this October, has been working for years to restore wild salmon runs that were destroyed by overfishing and horrible environmental practices including clear-cut logging, blanket spraying of pesticides, and the introduction of open pen-net salmon farms on an industrial scale.

Billy Proctor (Harvey Hochstetter)

In his autobiographical book (highly recommended) Heart of the Raincoast: a Life Story, co-authored by renowned naturalist Alexandra Morton, Proctor talked about the destruction he has seen over the years:

In 1957, the BC Forest Service did an aerial spray of the north end of Vancouver Island. They sprayed from Blinkhorn Peninsula in Johnstone Strait to Cape Scott, Nigei Island and Hope Island. They sprayed with DDT and they did it in May, just when all the fry and smolts were leaving the rivers. The reason they sprayed was to kill a bug that was killing spruce trees. I was in Goletas Channel on my way home from Bull Harbour when they were spraying Nigei Island. They used two big four-engine planes and they had a thousand gallons of DDT in each plane.

There were holes along each wing and as they went there was a fog behind them. This went on for a week or more. There were stories of people with wheelbarrows full of dead tiny fry from the banks of the Nimpkish River. After that, there were no big runs of coho or springs to the Nimpkish River.

… Traditional fishing grounds were barren and who was to blame? Loggers were damming streams, preventing salmon from going upriver, and clear-cut logging was killing eggs on the spawning beds. Salmon eggs incubating in gravel need a constant flow of water to survive, and when a hillside is clear-cut, the soil washes downhill with each rainfall, clogging the little spaces between the pebbles and smothering the eggs.

Clear-cutting also warms river water, which is deadly to the cool-loving salmon. Pesticides were flowing into the creeks, poisoning juvenile fish. Relentless, increasing fishing pressure meant fewer and fewer salmon were returning to these damaged rivers, further decreasing survival. No one knew what was happening to the fish once they were out to sea. Warm currents, lack of food and increased predation kill salmon where we never see it.

What is amazing, and infuriating, to me is that these ruinous, backward, and unsustainable—stupid—practices continue to this day, aided and abetted by the B.C. and Canadian governments. In the Broughtons we passed through channels which for majesty would rival Alaska’s famed Misty Fiords National Monument—were it not for mountains vandalized by fresh clearcuts, mile after mile, with large Atlantic salmon farms seemingly around every bend.

Here’s some of what we saw (all uncredited photos on this website by Andy Ryan):

Broughton Archipelago clearcuts

… and open net-pen fish farms

(Harvey Hochstetter)

(Harvey Hochstetter)

(Harvey Hochstetter)

***

Port Harvey to Campbell River, via Johnstone Strait

After four hours the fog in Johnstone Strait began to lift, and the shoreline slowly emerged. We could see again. The current had turned, going with us, and we were able to bring our boats up on plane and speed down the channel to Seymour Narrows. We got there an hour before the peak of the 14-knot ebb and rode the tide through churning rapids down to Campbell River.

Salmon trollers, tied at the dock, Campbell River (Harvey Hochstetter)

The salmon trolling fleet in this pretty town has been tied up at the dock all summer. Not enough fish for commercial openings, and no one can say exactly why. It could be the massive landslide that closed the Fraser River to fish passage earlier this year. Some say it could be Japanese drift-net fishing once again interdicting returning salmon. Or it could be the things people like Billy Proctor and Alexandra Morton have been warning us about—fish farming, logging, mining, industrial-scale application of pesticides, fertilizer runoff, loss of habitat, culverts and dams obstructing salmon migration routes.

All of these things are within our power to change. As the old Pete Seeger song goes, “I swear it’s not too late.”

Bad news for wild fish

Osprey passing an open net-pen salmon farm in the Broughton Islands this summer (Harvey Hochstetter)

DON’T BUY FARMED SALMON—and consider boycotting stores that sell it. Ask your friends to do the same.

As I’ve made my way along the British Columbia coast this summer, I have been struck by the number of floating fish factories—open net-pens containing hundreds of thousands of genetically altered Atlantic salmon—infesting these waters.

There is no rational reason I can see for the Canadian government to allow these ugly insults to the planet, which pose a very real threat to the five species of Pacific salmon that have sustained coastal people (and orcas and bears) for thousands of years. Salmon are the very soul of the North Pacific coast.

British Columbia’s neighbors, Alaska and Washington state, have implemented outright bans on net-pen salmon farming.

Bumper sticker seen at Alert Bay

The B.C. salmon farms, over 100 of them, are located along migration routes for native fish stocks, and there is conclusive scientific evidence that fish farms provide ideal breeding conditions for parasitic sea lice. The lice attach themselves to juvenile native salmon; it takes only two or three lice to kill a young fish.

According to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, “Wild salmon close to fish farms are 73 times more likely to suffer lethal sea lice than juveniles not adjacent to fish farms. A fish farm can also elevate the rate of sea lice infestation in salmon up to 40 miles from their pens. Sea lice can survive for about 3 weeks off their host—making transfer from farmed to wild salmon possible.”

Worse than sea lice, perhaps, up to 95 percent of open net-pen Atlantic salmon in British Columbia are infected with Piscine Reovirus, a highly contagious disease which can cause heart and skeletal inflammation in salmon. The strain of the virus found in B.C. fish farms is believed to have originated in Norway, introduced to the environment along with the farmed fish.

And yet, inexplicably, the Canadian government has pressed for regulations which would specifically allow disease-infected salmon to be introduced into B.C. net pens. Opponents of net-pen farms have been met with stonewalling in their attempts to obtain correspondence between industry and government scientists.

There are signs like this in villages up and down the B.C. coast. This one’s in Alert Bay

Salmon farming is big business, and you have to wonder if someone is getting paid off.

The many First Nations people I have spoken with along the coast this summer have expressed strong opposition to open net-pen salmon farming, which they see as a direct threat to their way of life. Salmon are at the heart of native spiritual and cultural practices, and are the most important subsistence resource for people who make their livings from the sea.

As of this date, Jonathan Wilkinson, Canadian minister of fisheries and oceans (along with Canada’s Coast Guard), has been unresponsive to their concerns about the hazards of net-pen salmon farming, local people have told me.

So before you buy that salmon filet, check where it came from. If it doesn’t say wild salmon, or if it says “Atlantic salmon,” don’t even think about buying it. You’ll be doing Mother Earth a favor; and besides, farmed salmon—treated throughout their lives with pesticides and antibiotics—doesn’t taste good.

Here are some photos Harvey took as we passed yet another net-pen operation in the Broughton Islands this week:

Two Harveys

Harvey Hochstetter and Sleepy C

MY FRIEND HARVEY HAS JOINED ME in Port McNeill. Harvey is another C-Dory owner, and for the next couple of weeks we’ll be buddy-boating through the Broughton Islands archipelago, at the eastern end of Queen Charlotte Strait.

Harvey brought Sleepy C up from Sequim, Wash. two weeks ago. Since then, he has been helping the owner of the Port Harvey (no relation) Marina, Gail Cambridge, get her possessions packed up for her move back to Alberta. Gail’s husband George died suddenly, a year ago, and Gail can’t run the marina by herself.

Harvey had come to know the Cambridges over a couple of summers cruising in the Broughtons; he became a more active supporter of the little mom and pop marina last year when a local man sought to have part of the bay rezoned, to permit the operation of a noisy, ugly shipyard directly across from the marina.

The Cambridges believed the industrial operation would destroy the solitude and quiet of their beautiful little cove. And their business along with it.

Port Harvey Marina

I followed the rezoning process from afar, reading local newspaper stories online and listening to first-hand accounts from Harvey, who drove up to Port McNeil to participate in the hearings. For a number of years I worked as a newspaper reporter, covering local, state and federal government—and from what I could see, in the pro-development environment that seems to prevail up here, the deck was stacked against the Cambridges. They never had a chance.

At one point, the marina’s dock sank, for no apparent reason. Harvey is convinced it had to have been sabotage.

On May 15, 2018, despite considerable local opposition, the Regional District of Mount Waddington adopted Bylaw 895, rezoning the Cambridges’ neighbor’s land—from “rural” to “marine industrial.”

In a news release sent out after the Mount Waddington District’s decision, George Cambridge said he would appeal the ruling.

“An industrial scale marine repair and salvage business being operated at this location is incompatible with all other adjacent uses,” Cambridge wrote. He added that the regional district violated one of its own bylaws, “that no rezoning bylaw can be enacted that allows a new use that is incompatible with existing adjacent uses.”

The Cambridge family

George set up a GoFundMe page in an attempt to raise the estimated $80,000 cost of fighting the ruling … and then everything ended for the Cambridges and the Port Harvey Marina. Three months after the zoning decision, George died in his sleep of an apparent aneurism.

And so, for the past couple of weeks, Harvey and a small band of friends have been helping Gail Cambridge pack up the memories of a long, happy marriage. A water taxi was scheduled to take her away this week. Harvey and I have plans to stop off at the now vacated marina, for a last look, on our way back from the Broughtons.