Along the spirit bear coast

Great Bear Rainforest (Source: Mapbox Streets)

FROM THE TIME I CROSSED FROM ALASKA INTO CANADA, across wide Dixon Entrance, I was in the “Great Bear Rainforest.” The name, a public relations masterstroke, was coined in a San Francisco restaurant one night in the late 1990s by environmentalists working to protect one of the world’s last great temperate rainforests.

“We wanted people to hear the name and be mad as hell that anybody could turn it into toilet paper,” one of the activists wrote in a later memoir. Local residents reportedly were not consulted in the naming, but it appealed to the media and general public, and it stuck.

After a well-funded international campaign, targeting big lumber suppliers like Home Depot, the British Columbia government threw in the towel. In 2016 the prime minister declared 85 percent of the rainforest off limits to commercial logging. Depending on which website you want to believe, the protected area encompasses most coastal areas of northern B.C., and is between 12,000 and 22,000 square miles in size.

(If I’m getting any of is wrong, please let me know and I will make appropriate corrections.)

For the past two weeks, I have been slowly working my way down the outer coast of the rainforest, among dozens of archipelagos, hundreds of islands, with winding passages leading out to the ocean. Three of these outer islands are home to a rare subspecies of black bear—the Kermode or spirit bear (Ursus americanus kermodei). Ten to 20 percent of Kermode bears here—from 100 to 500 individuals—are white and I had hoped I might see a white spirit bear. But not this trip; I’ll have to come back.

This place is sacred to the indigenous people whose home it has been for thousands of years. And now it’s sacred to me.

Here’s some of what I saw along the way:

Prince Rupert docks in the fog, from Casey Cove

Kelp beds on outer coast reef

Fog rolls in on the outer coast

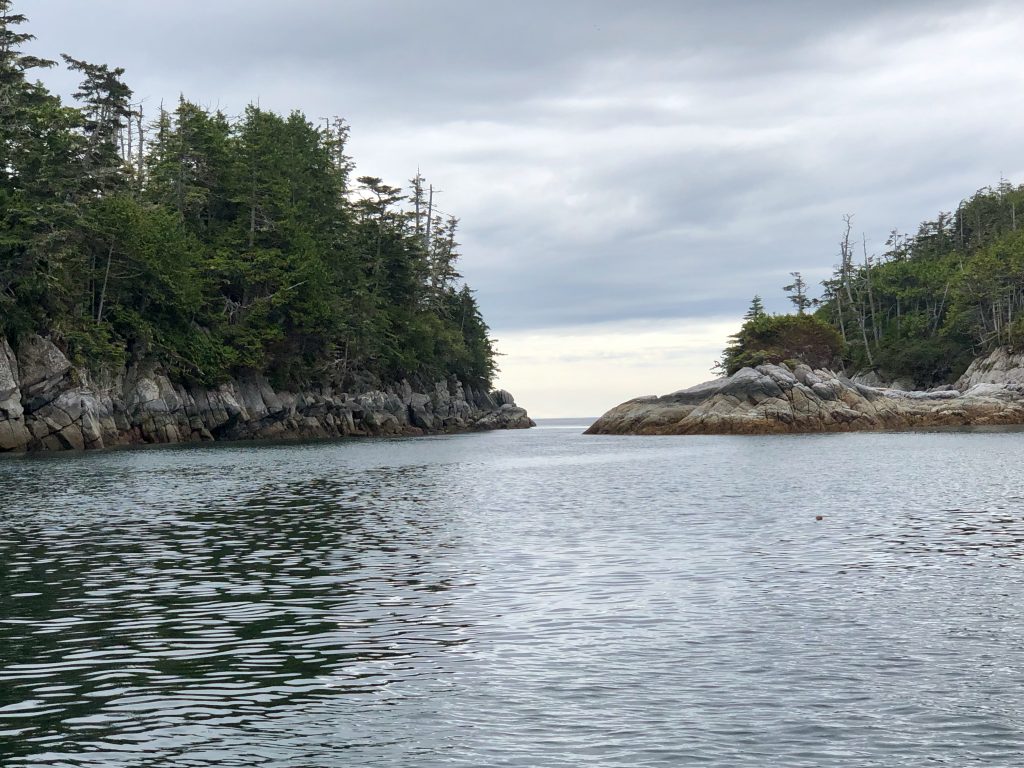

Island passages …

… around rocky points

Sometimes with the assistance of lighthouses …

Robb Point Light

Dryad Point Light, north of Bella Bella

A jellyfish nursery at Lewall Inlet (look very closely, there are several)

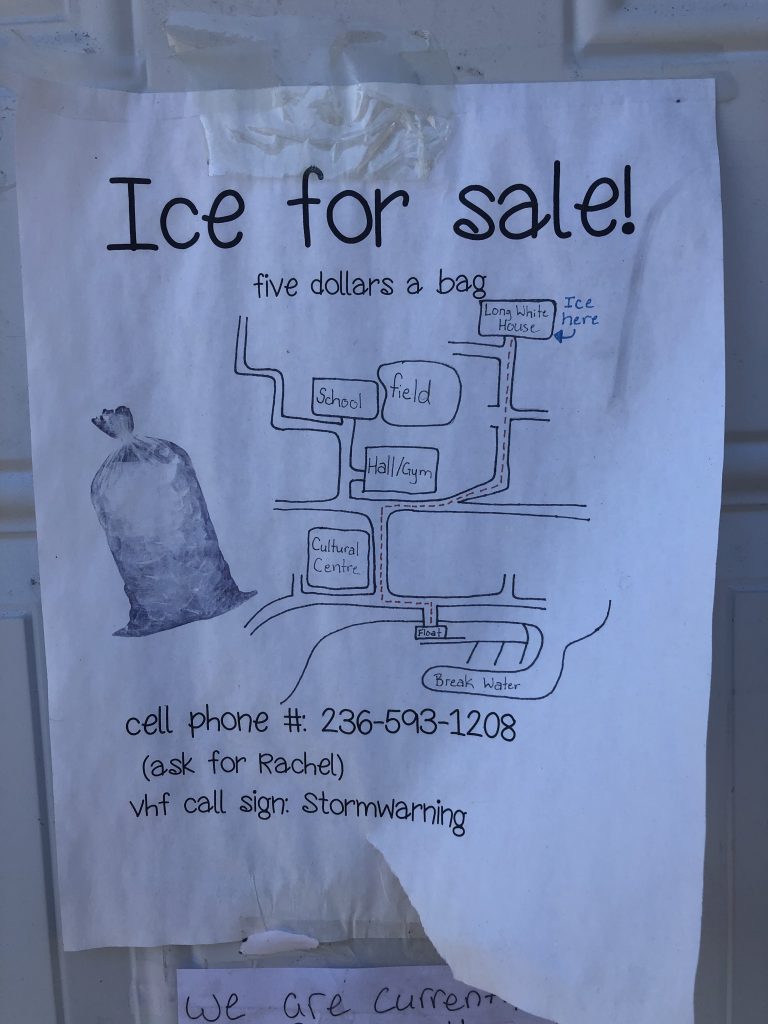

Ice for sale at Klemtu

Mt. Buxton, Calvert Island

Around Cape Caution

Cape Caution

And into Murray Labyrinth, where it was time for reflections.

Nathan and Dorica Jackson

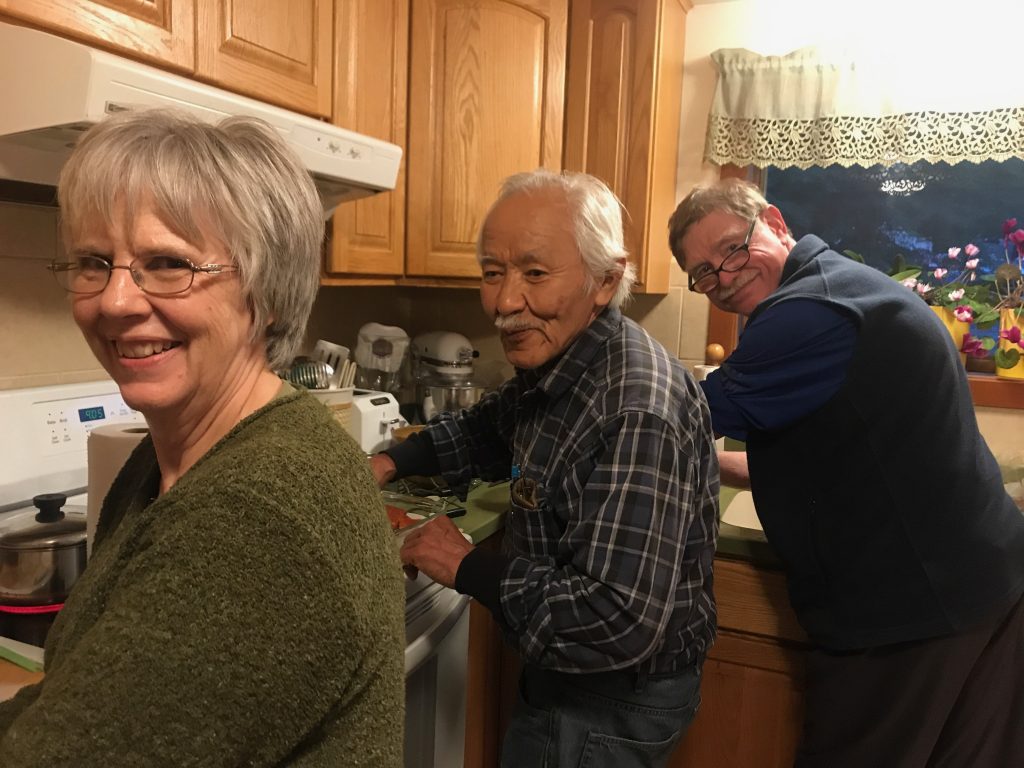

Dorica and Nathan Jackson (left) and Andy Ryan canning sockeye salmon in the Jacksons’ kitchen (Marla Williams)

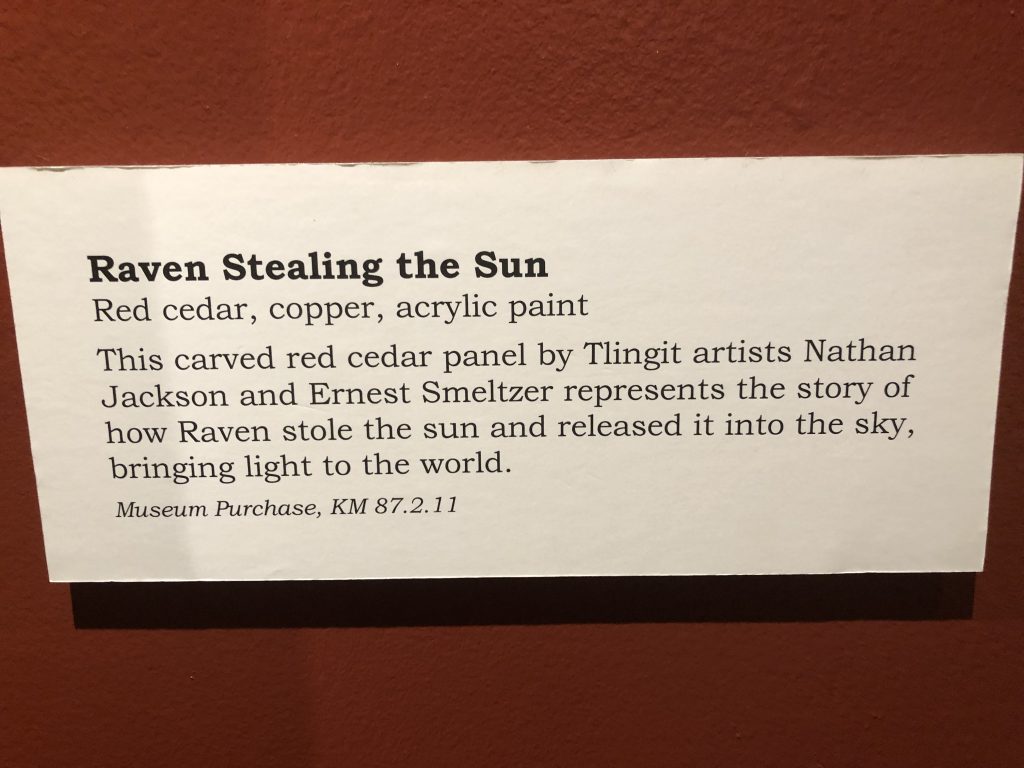

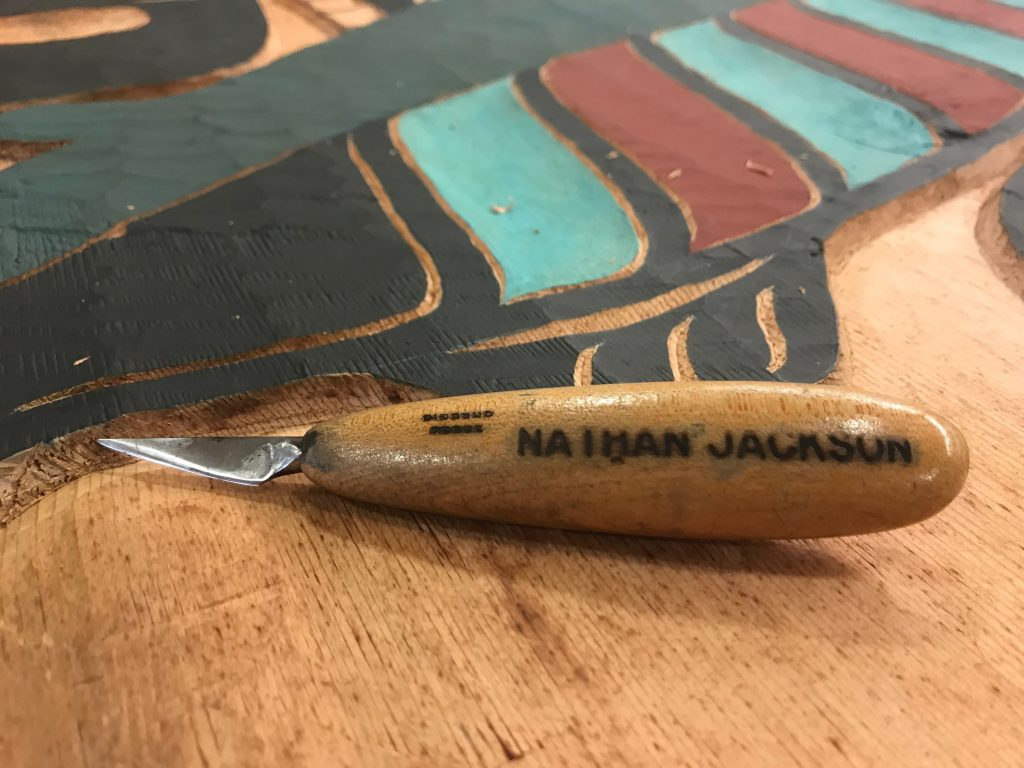

MARLA AND I WERE HONORED TO HAVE DINNER, twice this week, with renowned Alaska Native artist Nathan Jackson and his wife, master weaver and textile artist Dorica Jackson. After our second dinner with the Jacksons, at their home near Ketchikan, we helped them put up a mess of sockeye salmon Nathan caught earlier in the week, purse seining.

If you’re not familiar with Nathan’s spectacular work, you can see examples of it, here.

Raven Stealing the Sun, by Nathan Jackson and Ernest Smeltzer. Displayed at the Totem Heritage Center, Ketchikan

Nathan is the subject of a documentary by Marla, which begins airing this September on Alaska Public Media. The film is one in a six-part series, Magnetic North: The Alaskan Character.

Nathan Jackson airs Sept. 9, at 9:30, on Alaska Public Media. The series also includes films about:

—Clem Tillion

—Arliss Sturgulewski

—Roy Madsen

—Jacob Adams

—Bill Sheffield

The series is directed by Marla and edited by Kyle Seago. Funding provided by Rasmuson Foundation in association with the Alaska Humanities Forum.

For more information email akhf@akhf.org

Here are a few more photos from our visits with the Jacksons:

In Nathan’s workshop (Marla Williams)

Nathan, preparing sockeye for canning (Marla Williams)

Jars of salmon, ready for the pressure cooker (Marla Williams)

Dorica Jackson (Marla Williams)

Chilkat robe by Dorica, recently purchased by the Ketchikan Museums Department, with help from a Rasmuson Foundation grant. (Photo courtesy Ketchikan Museums)

Pit stop in Ketchikan

Ken Perry, Timber & Marine Supply, Ketchikan

ONE OF THE BIGGEST MISTAKES I MADE in preparing for this trip was neglecting to ask my outboard motor dealer if I would be able to get service on my way north for the new Tohatsu 50s I was considering buying.

Outboards require service every 100 hours, and I figured the trip would put at least 300 hours on the engines. I foolishly assumed that, because I had told the dealer I was buying the motors for a trip to Alaska, I would be able to get them serviced along the way.

Oops. It wasn’t until after I’d purchase the Tohatsus that I started trying to line up service appointments for the trip. I learned there are no Tohatsu dealers north of Nanaimo, on lower Vancouver Island.

Fortunately I was able to talk Ken Perry, owner of Timber & Marine Supply, into servicing the engines when I arrived in Ketchikan. But he gave me unceasing (but good-natured) grief about it every time I saw him. Ken asked for my dealer’s email address—for the purpose, I thought, of inquiring about Tohatsu parts.

Not exactly. Here’s what Ken wrote to my dealer:

“FYI for your future customers, why did you sell your customer (Andy Ryan) a pair of Tohatsu motors for his C Dory, knowing that he was going to travel through the inside passage of Alaska? There isn’t a single Tohatsu service center or dealer in any of Southeast Alaska. I also understand that you are a Honda Marine Dealer.

“There are multiple Honda Marine dealers in Canada and multiple Honda Marine dealers in S E Alaska. You can get a Honda outboard serviced in almost any town and no one will touch a Tohatsu Outboard. I’m just trying to save your future customers from heart ache and disapointment.

“Thank You Ken”

Ken’s shop did great work on my engines on my way north, and I stopped at his shop again on my way back south. After subjecting me to some mild ridicule, he serviced the engines—and said the Tohatsus and I would be welcomed back if I ever venture north again.

But Ken’s larger point is well taken: if the Tohatsus break down between here and Nanaimo, I may need a long, long tow home.

Wind

Windy day in Clarence Strait, seen from Meyers Chuck

DAVE POINTED TO THE DARK MASS OF CLOUDS over Anan Lagoon to the south and said in classic meteorological understatement, “It’s going to rain in about an hour.”

I hadn’t been been paying attention to the weather. Osprey was snugged into a little cove in front of the Anan Bay cabin, tied to a Forest Service float. Very protected. Dave was starting dinner. A floating Forest Service rangers’ cabin was anchored to our south, further out into the bay.

Then the wind hit—more suddenly than anything I’ve experienced, transforming the cove in seconds from a flat calm duck pond to a churning, frothing washing machine.

The float was bucking like a terrified horse, and Dave bravely climbed out of our boat and onto the pitching platform to tie down our kayaks, which were about to blow away. Then he quickly climbed back into Osprey. And we just watched.

Cove at Anan Bay on a calm day, with float and floating Forest Service rangers’ cabin (USFS photo)

It was remarkable: although there were only a few feet of fetch—the distance over which wind blows without obstruction to generate waves—a white line of two-footers marched across the narrow cove, slamming into the float. It happened too fast for us to be afraid; we were awestruck.

For less than a minute the wind seemed to slacken … and then the rain came, in sheets, sideways, obscuring everything around us. I bet it dumped two inches in less than three minutes. And then, as quickly as the storm had blown in, it was calm again.

But something was different, and it took a little while for us to realize what it was. The float to which we were tied was closer to shore; and the floating rangers’ cabin, which had been well to the west of us before the storm hit, was now less than 100 feet away.

Forest Service rangers’ cabin close to Osprey’s bow after dragging anchor during wind storm

We called the floating cabin on our VHF radio. The three Forest Service employees aboard—who now appeared to be anxiously evaluating the cabin’s new position—confirmed that all four of the cabin’s anchors had dragged. And from their vantage point, it seemed clear our float’s anchors had dragged as well. They told us they thought their anchors had finally dug in … but we all kept close watch through the night, just in case.

The next morning we made a quick trip to the Anan Bay bear observation station—no grizzlies and only a couple of black bears. There were salmon in Anan Creek, however, and the bald eagles were thick.

Our national symbol

Assemblage of eagles at Anan Lagoon

Black bear, heading for the woods

Brook running into Anan Lagoon

Then we got back on the water—and met more wind. We had intended to go from Anan Bay to Thorne Bay, with a seven-mile crossing of blustery Clarence Strait. But the weather was from the south, and forecasters were calling for 15- to 20-knot winds in the strait for the next four days.

So, rounding Lemesurier Point into Clarence Strait, we stuck close to the eastern shore, heading south into a four-foot chop, and ducked into the protected harbor of Meyers Chuck.

Meyers Chuck, refuge from the storm

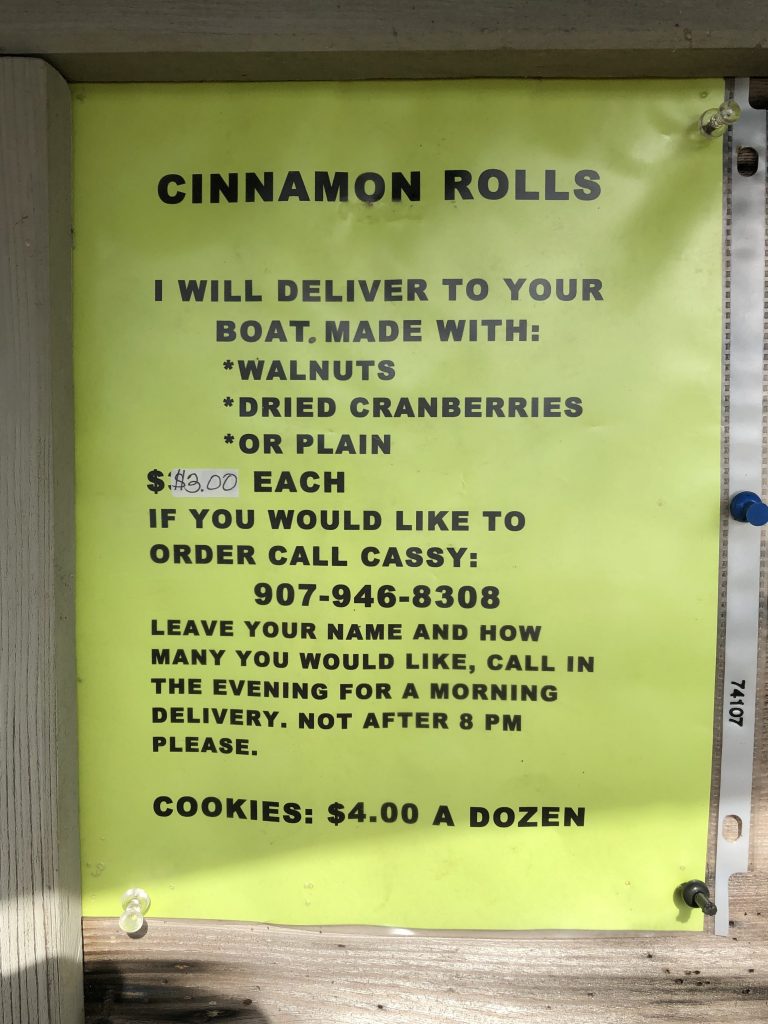

The next morning, as she had on the outbound leg of Osprey’s voyage, legendary Meyers Chuck baker Cassy brought fresh, homemade cinnamon buns right down to the boat.

But there wasn’t a minute to spare. It looked like we had a very brief weather window, maybe a couple of hours, before Clarence Strait got rough again. So, munching on Cassy’s cinnamon rolls, we scooted out of Meyers Chuck and ran, 32 miles through heavy chop, down to Bar Harbor, in Ketchikan.

Rocky Pass and Point Baker

Two Trees Island, near Wrangell

IN HIS EPIC BOOK SAILING ALONE AROUND THE WORLD, Joshua Slocum recounts “the greatest sea adventure of my life” — finding himself at night in “the Milky Way of the sea,” northwest of Cape Horn, amidst huge breakers over sunken rocks in every direction.

“What a panorama was before me and all around,” wrote the world’s first solo circumnavigator. “What could I do but fill away among the breakers and find a channel between them … God knows how my vessel escaped.”

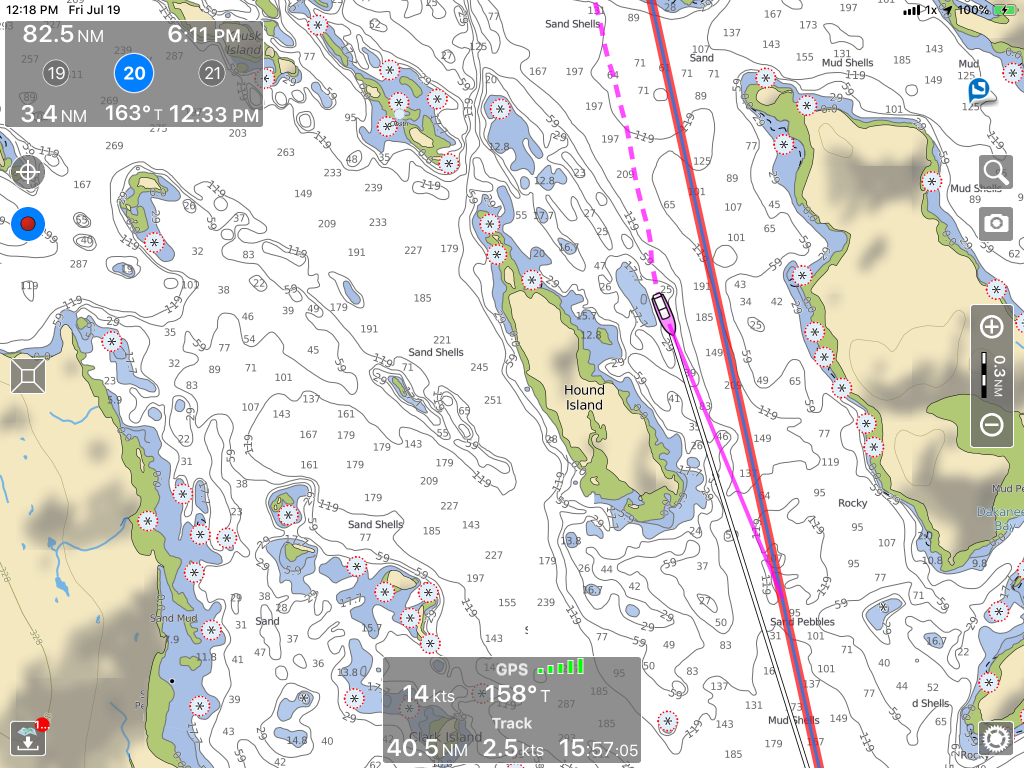

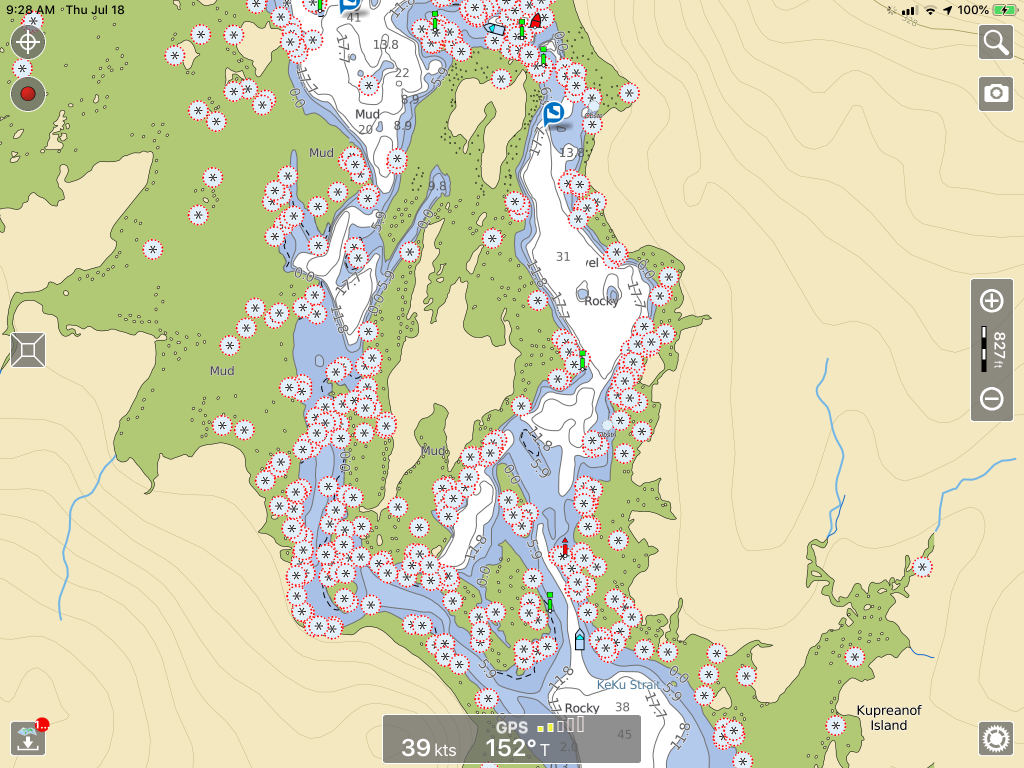

I was reminded of Slocum’s Milky Way when I looked at the chart of Rocky Pass, a twisty, rocky, shallow passage separating Kupreanof and Kuiu Islands. My first thought was, “Let’s not go that way.”

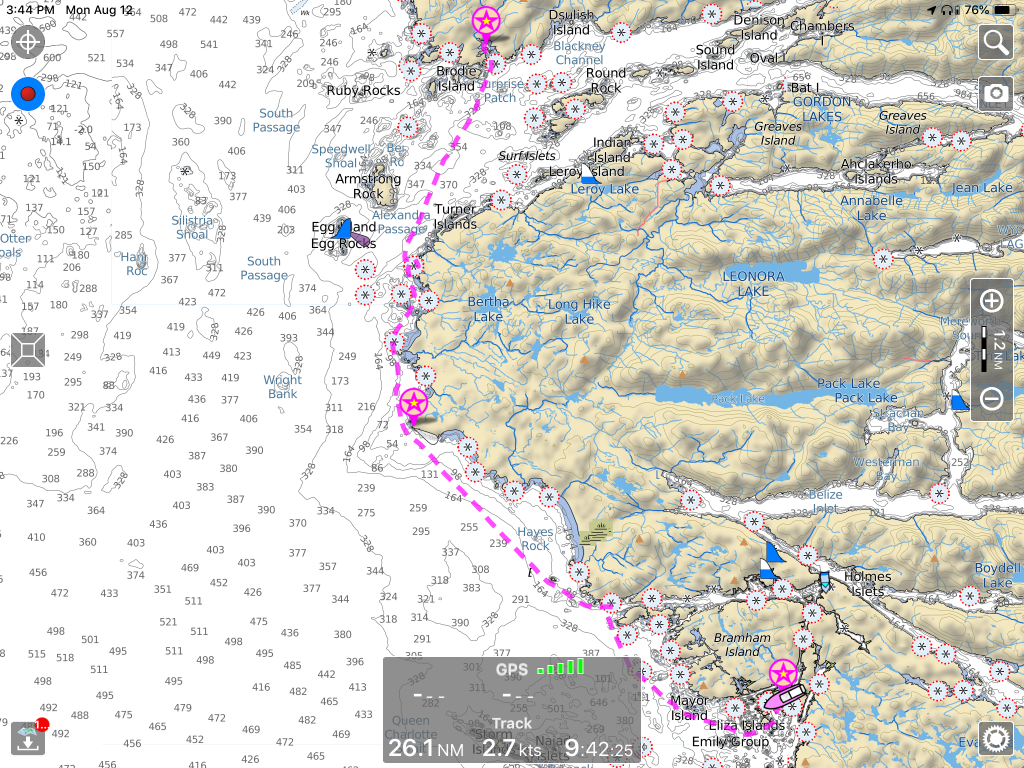

A section of Rocky Pass (the asterisks are rocks)

But despite its somewhat fearsome reputation, Rocky Pass was an easy passage for nimble, shallow-draft Osprey. Against all online, crowd-sourced advice, we went through the pass from the north at low tide, making easy headway against a strong northbound current. Weaving around thick mats of kelp was the greatest challenge; and at one point I had to raise one of the motors to remove kelp from the cooling water intake.

Emerging from Rocky Pass, we headed south across wide Sumner Strait, to the hamlet of Point Baker, population, 25, on the northwest tip of Prince of Wales Island. Point Baker is said to be home to Alaska’s last floating tavern, so of course we had to visit.

Floating Point Baker Trading Post store and bar

Osprey at Point Baker Trading Post

Sisters Juli Bowes and Annette Hoyt behind the bar at the floating Point Baker Trading Post

Juli and Annette’s dad, Herb Hoyt, bought the place back in the 80s. Juli was working the bar, while Annette—who went to culinary school—was back in the kitchen, fixing some of the yummiest burgers we’ve sunk our teeth into.

Juli spends her winters in Lake Havasu; and when the Trading Post closes for the season, Annette heads back to the Raymond, Wash. area, where she hunts Roosevelt elk.

Seated next to Dave Ortland and me at the bar were brothers Jim and Dave Engel from Saugatuck, Mich., who were up here with their wives, salmon fishing. Dave Engel is a charter fishing guide back home, and when the local bait of choice—herring—failed to do the trick, he switched to Michigan-made lures. Result: a handsome pair of king salmon.

Dave Engle with a pair of kings, caught the Michigan way

Dave Engle with the tools of his trade

Michigan-made Spin Doctor mirage (a color) Strong Flies

From Point Baker, we motored back across Sumner Strait, to an anchorage in Totem Bay—and a glorious sunset.

Sunset at Totem Bay

Along the way we saw:

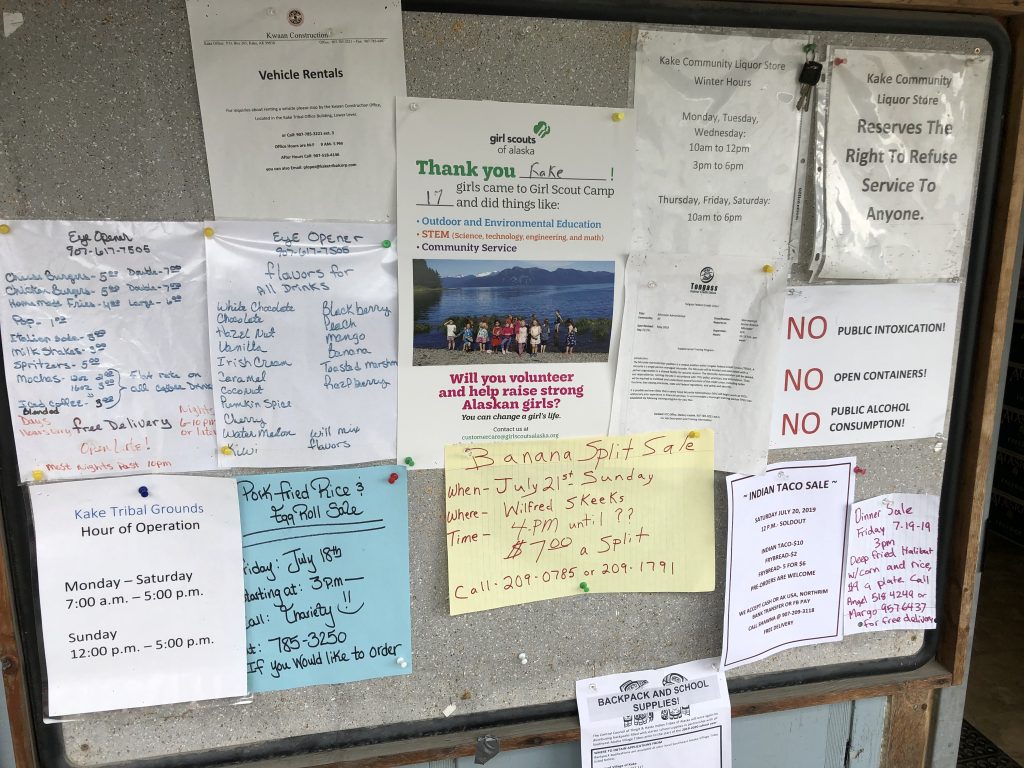

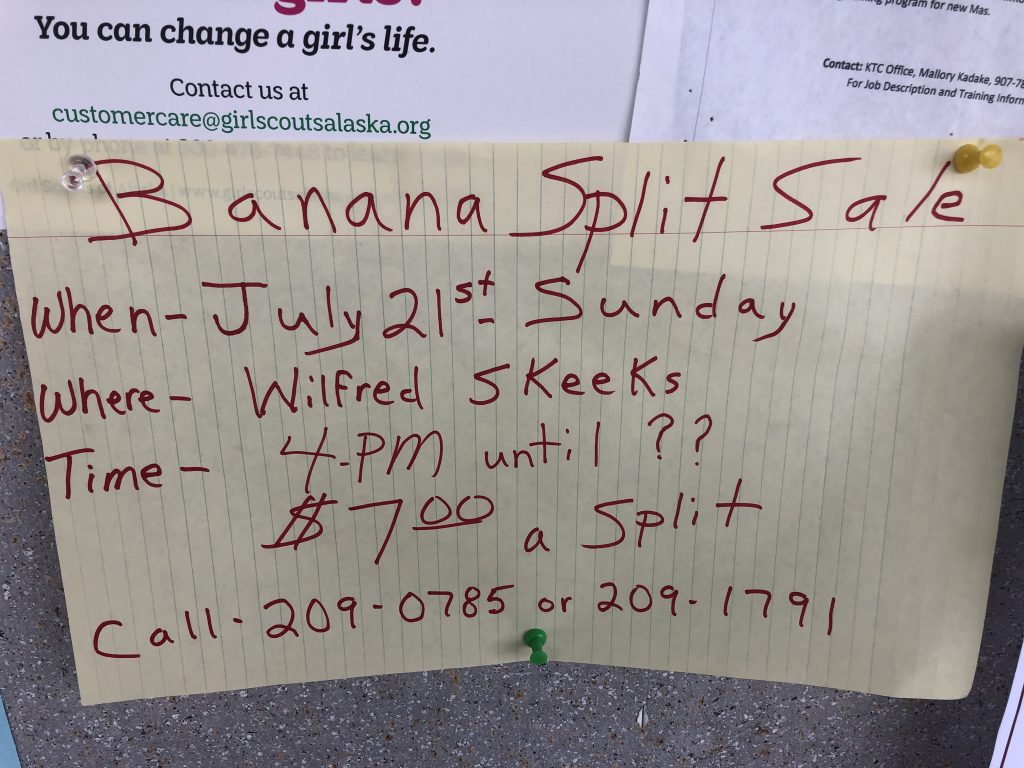

Kake, a quiet Tlingit village, population 710, on the west side of Kupreanof Island

Community bulletin board at Kake

Memorial on public dock at Kake

Hound Island

Secluded anchorage in Port Camden

Fishing boat entering Wrangell Harbor

Tracy Arm, whales and sea lions

Tracy Arm passage

WE WERE ENTERTAINED LAVISHLY last night at the home of Rocky and Sue Flint, whose new home has a spectacular 180-degree view of Frederick Sound. After dinner Sue’s sister, former Petersburg First Lady (FFL) Sally Dwyer drove us around this friendly, hard-working burg.

Sally has deep roots in this community, which takes tremendous pride in its Norse heritage. Her grandfather ran a cannery here, with a fleet of fishing boats, and was, among other things, the town’s mayor. Her dad was a commercial fisherman, and her late husband Al was also mayor.

I wish we could stay here for a month, but Dave has a plane to catch, in Ketchikan in a few days, so we’re off in a couple of hours. Next stop Kake and the west side of Kupreanof Island, with a passage of twisty, Rocky Pass, which—as the chart shows—more than lives up to its name.

Portion of Rocky Pass

Here’s a photo gallery of the sights we’ve seen since my last post, starting with our visit to Tracy Arm and the South Sawyer Glacier:

South Sawyer Glacier

Whales, between Point Hobart and Five Fingers Light

Sea lions at Sunset Island

Thomas Bay

Dave Ortland prepares Thai dinner

Dave texting in Thomas Bay

Petersburg

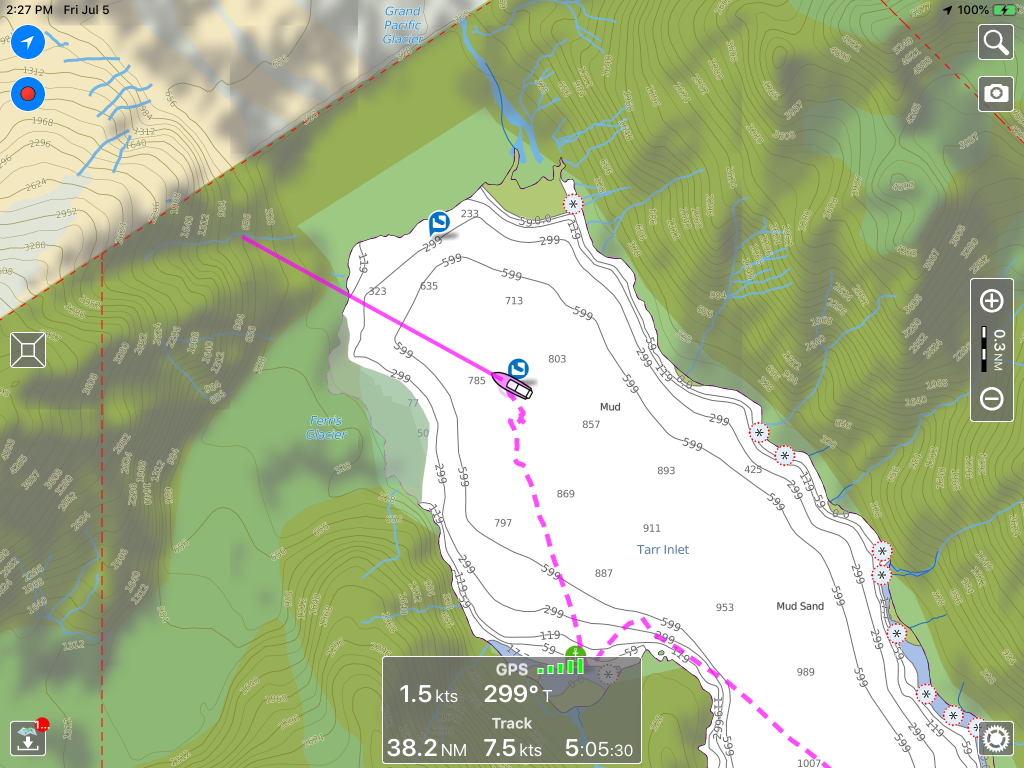

Glacier Bay and environs

Glacial valley in Tarr Inlet, Glacier Bay

GLACIER BAY WAS FILLED WITH SMOKE from dozens of forest fires in the Yukon Territory and interior Alaska, and the sun was a weird shade of orange for much of the time we were in the national park.

And It really didn’t matter. We were too busy watching beautiful things—whales, sea otters, bears and glaciers—to think about the dramatic environmental changes washing over our planet. We’ll get back to worrying about that when we get home.

Kinnon and I are back in Juneau now after traveling over 300 miles in eight days—to St. James Bay, Couverden Bay, Hoonah, Glacier Bay, Dundas Bay and Elfin Cove. Kinnon flies out tomorrow, I’ll pick up my fourth passenger, Dave Ortland, at the Juneau airport at 9 a.m. And then we’ll be off for the glaciers of Tracy Arm.

I’ll post more words and photos when I get to Ketchikan, in about two weeks. But in the meantime, here’s a taste of what we’ve seen:

Glaciers

Glaciers

… and more glaciers

Gulls on ice flows

Ice flow gulls (Kinnon Williams)

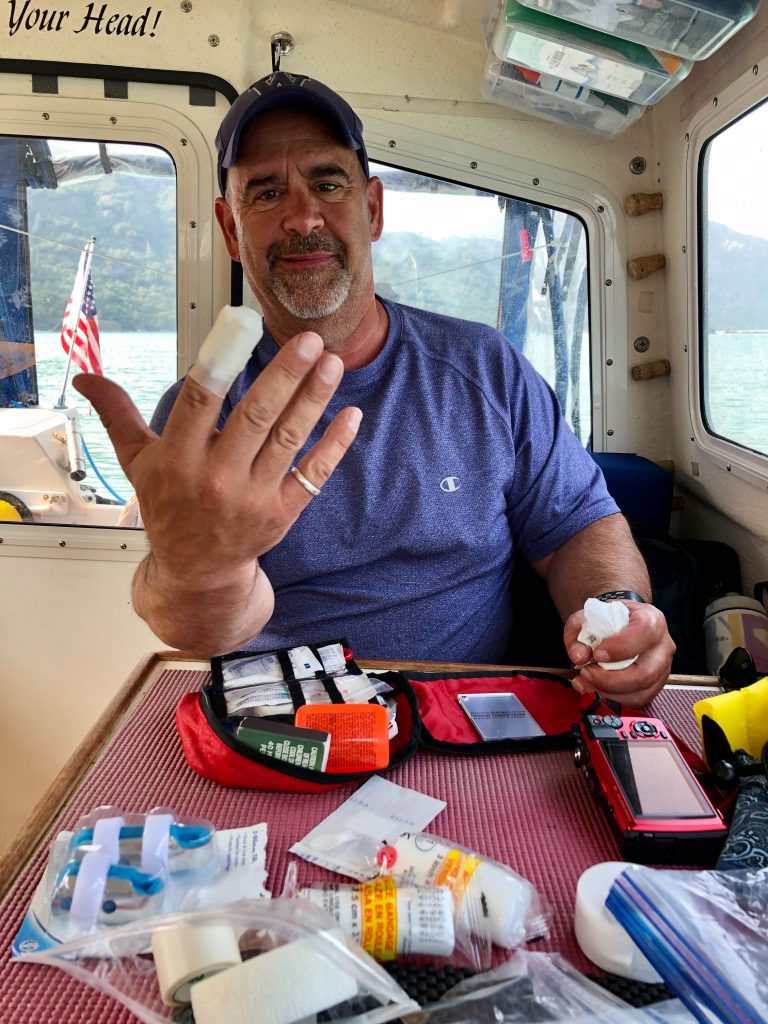

Kinnon came close to cutting off the end of his finger

But it didn’t stop him from grabbing a small hunk of Glacier for our ice chest

Smoky sunset over Sandy Cove, Glacier Bay

Sea lion (Kinnon Williams)

Humpback whales (Kinnon Williams)

Humpback whale (Kinnon Williams)

Sea otter, feasting (Kinnon Williams)

Black bear, Shag Cove

Shag Cove bear

Northernmost point of our trip, in Tarr Inlet, just south of Canadian border

Carvings in Huna Tribal House, Bartlett Cove, Glacier Bay

Huna Tribal House detail, Bartlett Cove, Glacier Bay

Huna Tribal House detail, Bartlett Cove, Glacier Bay

Huna Tribal House detail, Bartlett Cove, Glacier Bay

Village on a boardwalk: Elfin Cove

Elfin Cove general store

Elfin Cove intersection

Osprey at Elfin Cove

Kinnon at Hoonah

Hoonah, from the water

Alaska’s capital, Juneau

Near the end of Glacier Highway, Juneau

MY WIFE MARLA AND I MET AT A MURDER-SUICIDE in Anchorage, and a few months later we moved to Juneau. We were both reporters. Mar covered Alaska government for a statewide radio network; I wrote for the Anchorage Times. We moved to Miami in 1985 for work. That was almost 35 years ago, and I haven’t been back here since.

In the intervening years, The 49th state’s capital city has grown by about a third (to 32,000 in 2014) and, in summer months, enormous cruise ships daily discharge thousands of tourists onto city streets. If you decide to visit, try and pick a time when one or more of the 5,000-passenger megaships isn’t docked downtown.

Marla has flown here with her brother, Kinnon, who will be traveling with me to Glacier Bay and back. My brother Bill is heading back to New York City. The infestation of cruise ships not withstanding, I still love this special town, which can only be reached by boat or plane.

Our old neighborhood (Marla Williams)

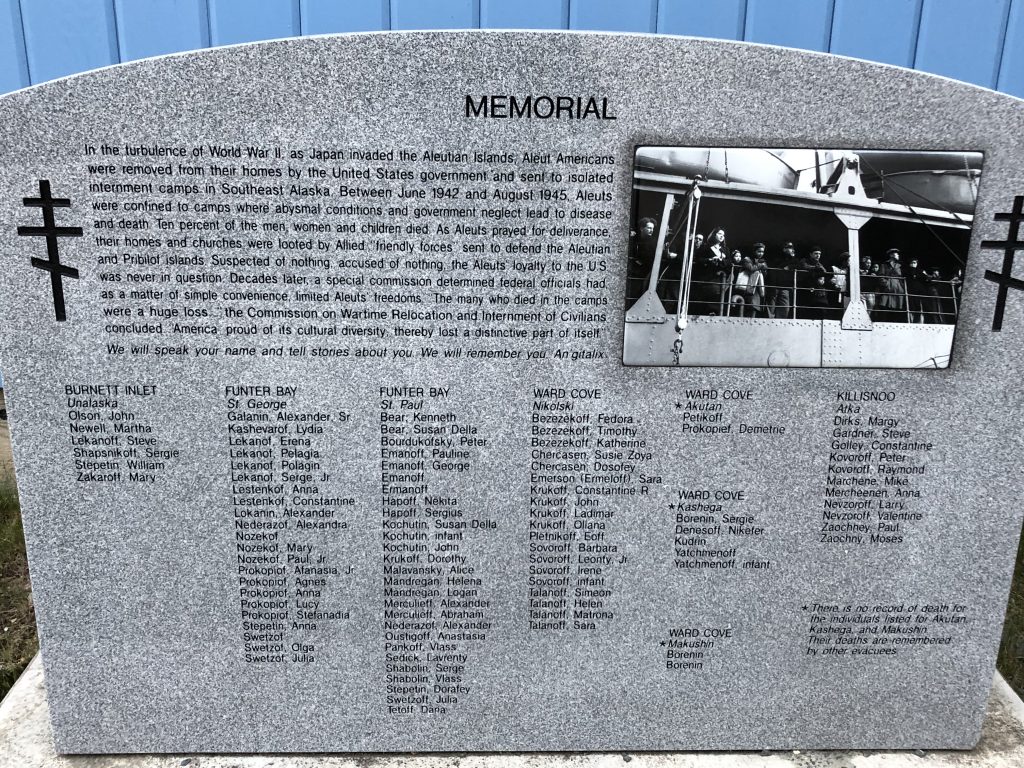

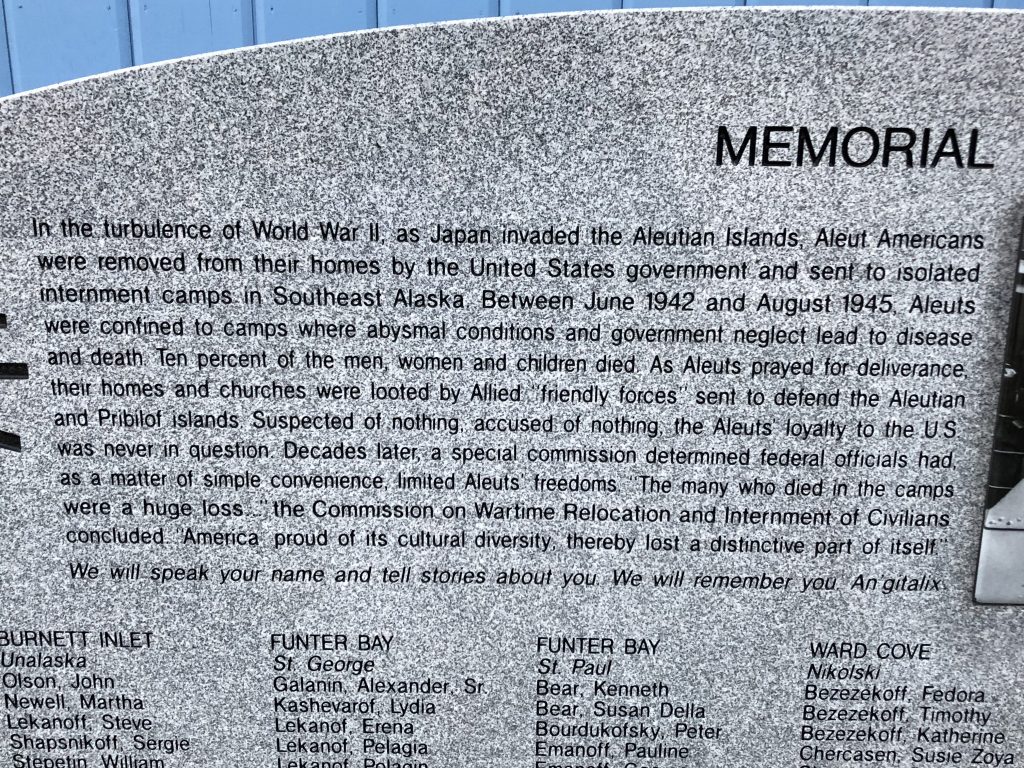

In 2016 the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Restitution Trust and the Aleutian Pribilof Heritage Group placed a memorial at the St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church, to the Unagan people who were forcibly removed from their homes during World War II and sent to internment camps in Southeast Alaska. Marla was privileged to write the words for the memorial.

Memorial stone at St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church

Detail from the memorial stone

Detail from the memorial stone

Osprey crew member Kinnon Williams at St. Nicholas Church

In Juneau we saw:

Humpback whale sculpture by local artist R. T. “Skip” Wallen

Mendenhall Glacier view (Marla Williams)

Eagle River, north of Juneau

Petersburg to Juneau: creatures abound

Seals floating in Endicott Arm near Dawes Glacier (Bill Ryan)

ALASKA’S FAUNA WERE ON FULL DISPLAY as the Osprey made her way to Juneau from Wrangell. Brown bears, seals, eagles and ice animals practically posed as we went by, a photographer’s dream.

We stocked up in Petersburg, a scenic, orderly fishing town proud of its founders’ Norwegian and Native heritage. Sally Dwyer, a longtime civic leader, gave us a fascinating VIP tour.

Houses along Petersburg’s Hammer Slough (Bill Ryan)

For the next five days we cruised into the wilderness to see animals, snow-capped mountains and glaciers, on a blessed run of sunny days. At night we anchored in protected coves, after reading reviews by other mariners and gingerly sounding the surrounding depths.

Entering Stephens Passage from Frederick Sound we crossed a virtual whale highway. We heard spouting and saw dozens of plumes in all directions, and from afar glimpsed a few tails reflecting sunlight as they flopped into the water.

Near shore, eagles were constantly overhead.

Bald eagle watching over Windham Bay (Bill Ryan)

At Hokham Bay we first encountered jagged icebergs calved from glaciers at the ends of Tracy Arm and Endicott Arm. Gleaming in the morning sun, some odd shapes suggested birds, lizards or dragons.

Ice menagerie: What manner of creature is this? (Bill Ryan)

Rising at 4 a.m. to meet the tide, we made our way up to the challenging entrance of Ford’s Terror inlet—named for a frightened sailor who navigated the roiling rapids in a rowboat—and at slack water went through carefully, into a secluded paradise enclosed by stunning high cliffs and waterfalls. No gargantuan cruise ships here.

View from our anchorage at Ford’s Terror (Bill Ryan)

We stayed long enough for two short kayak rides to a beach at one end of this idyllic basin. Rounding a bend, I suddenly came upon a mama brown bear and two small cubs digging for crabs or clams. After backing off to avoid notice, I took pictures from the kayak, rueing my lack of a longer lens. The mother and cubs then swam across a rising creek and vanished in the woods.

Brown bears dig the beach at Ford’s Terror (Bill Ryan)

When the tide was higher, I paddled back to their digging site, now an island, and found bear tracks and multiple holes in the sand.

Remnants of the three bears’ beach excursion (Bill Ryan)

The next day we continued up Endicott Arm to Dawes Glacier, weaving through a maze of small icebergs. Seals basked idly on many of these floats.

‘You looking at me?’ (Bill Ryan)

We got as close as we prudently could to the massive ice cliffs where the glacier meets the water, sharing the awing experience with kayakers from a swanky yacht.

Dawes Glacier (Photo: Bill Ryan)

We anchored for the night near the entrance of Tracy Arm, another fjord famous for icebergs, sharing the cove with tour boats and pleasure craft. As we pulled in, we spotted a brown bear family walking along slowly along the shore, as I and other tourists in inflatable rafts snapped pictures. Then they saw us and slipped behind the tall grass.

Foraging bears seem at first not to notice the spectators offshore (Bill Ryan)

Now they see us (Bill Ryan)

A trio of eagles watched from a rock as we pulled out into windy Stephens Passage, where we faced two- to three-foot waves from several directions. Our ride toward Juneau was bumpy but manageable, and the mountains on all sides were magnificent.

Eagles rest between fishing flights (Bill Ryan)

On our last night out in this leg of Osprey’s journey we anchored by a beach in a tranquil cove off Admiralty Island, reputed home to North America’s largest brown bear population. No creatures were sighted onshore, but in a sunset that lasted past midnight we listened to a nearby whale’s spouting and splashing, sounds that boomed across the water. Suddenly there was a commotion, and close behind our stern up popped two seals swirling in a close embrace.

Seal pas de deux in the sunset (Bill Ryan)

After a couple of days’ respite and a crew change in Juneau, brother Andy and his cozy C-Dory will head off to the natural glories of Glacier Bay. Bon voyage. Quelle aventure.

Wrangell and the boat next door

Hand troller Mij at Wrangell

BEHIND US ON THE WRANGELL DOCK this afternoon was the 26-foot hand troller Mij. Her owner, 29-year-old Brittaney Schunzel was replacing a damaged rub rail.

Trollers pull long fishing lines behind them, attached to “troll poles”—outriggers—extending from either side of the boat. Power trollers, which pay more for their licenses, get to put out four lines and use mechanically powered reels to pull them in. Hand trollers are only allowed two lines, which they crank in by hand.

Trolling for salmon, by hand or power, is hard work. The fishing lines running from the troll poles are from nine to 28 fathoms long—a fathom is six feet—and shorter leaders with hooks at the ends are attached every nine feet. That’s as many as 36 lures on a hand troller, each of which may have hooked a salmon.

Skipper Schunzel in Mij’s galley

Brittaney shows lures for king and coho salmon

From July through mid-September Brittaney fishes for coho and king salmon, and she’s been making a living at it. Last year buyers were paying fishers $8.25 a pound for king salmon, and as much as $2.60 a pound for coho. She hopes this year’s prices will be as good as last’s; but this year her season will be cut short in August, when she’ll fly up to Anchorage to begin nursing school.

Will Brittaney be able to combine nursing and fishing? She hopes so. She loves her cozy, immaculate little boat and can’t even begin to think about selling her. Just maybe, she thinks, when school is done, she’ll be able to find nursing work in Wrangell, and live aboard Mij.

It makes me very happy to think Brittaney might be able to pull that off.

Brittaney and Mij

Since I last posted, Bill and I have motored from Knutson Cove to anchorages at Meyers Chuck (where longtime resident Cassy delivered her delicious homemade cinnamon rolls right to our boat), Thorne Bay and Anan Bay last night (where we saw our first brown bear.)

Along the way we have also seen:

Meyers Chuck’s most famous attraction

Small lumber mill at Meyers Chuck

Playground apparatus at Meyers Chuck

… and a slide

… and a teeter totter

Visitors at the Meyers Chuck Dock

Andy selfie at Thorne Bay

Bill launching from the float at Anan Bay

Forest Service Cabin at Anan Bay (Bill Ryan)

Sunset at Anan Bay (Bill Ryan)

Morning view near Berg Bay (Bill Ryan)

Repairs on tidal grid, Wrangell

View across inner harbor, Wrangell